PROXY MONITOR

REPORT

Winter 2012

Shareholder Activism: What to Watch for in the 2012 Proxy Season

By James R. Copland

As America’s largest publicly traded corporations enter their annual meeting cycle, their boards and management can again expect to face various proposals submitted by shareholders for a vote of all owners of equity stock. Such proposals, which the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) typically requires companies to include on their annual proxy ballots, seek to change the relationship between shareholders and management or to change corporate behavior directly.

In 2012, three classes of shareholder proposals deserve particular focus:

- Political Spending Proposals. These proposals call for companies to disclose, limit, or require shareholder votes on corporate political spending, lobbying, or trade-association membership. In recent years—in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,[1] which held that independent political expenditures, including those by corporations, were free speech protected by the First Amendment—there has been an increase in the number of these proposals.[2] Although no such proposal has passed to date over management’s opposition, these proposals deserve continuing scrutiny, given their frequency and prominence.

- Proxy-Access Proposals. These proposals seek to allow shareholders, under certain conditions, to nominate their own directors on corporate proxy ballots. In 2011, the SEC approved amendments to its Rule 14a-8 to permit shareholder proposals in this area, after a federal court overturned the commission’s proposed mandatory rule granting certain classes of shareholders proxy ballot access.[3] In 2012, such proposals have already been prompting corporate reactions.[4]

- Chairman Independence Proposals. These proposals require the company to have a board chairman independent from the chief executive officer. Such proposals have been among the more common shareholder proposals seeking to change companies’ corporate-governance rules in recent years, though they have been less likely to garner support from a majority of shareholders than have proposals relating to voting rules, the terms of director elections, or shareholders’ ability to take action outside the annual meeting process.[5] These proposals warrant special scrutiny this proxy season, however, in light of labor-union pension funds’ announced intentions to pursue this issue in 2012.[6]

In addition to proposals submitted by shareholders, 2012 will mark the second year in which public companies have to submit their executive pay packages to shareholders for an advisory vote as newly required by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010.[7] In the first year of such so-called say-on-pay rules, shareholders at the overwhelming majority of companies voted to hold such votes annually, even as they overwhelmingly backed boards’ proposed pay plans.[8] Despite majority support for executive pay packages at almost every large company, such say-on-pay votes deserve continuing scrutiny this proxy season, given the fall 2011 decision by Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), the largest proxy advisory firm informing and making recommendations to institutional investors on shareholder proposal votes, that it expects management to respond whenever 30 percent or more of shareholders voted against management’s proposed executive compensation plan.[9]

Before turning to the upcoming proxy season in more detail, Part I of this report looks at shareholder-proposal activity retrospectively by summarizing trends among the 200 largest companies by revenues from 2006 through 2011, as recorded in the Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database (see “About Proxy Monitor,” below). Part II of the report looks at the three aforementioned classes of shareholder proposals that promise to feature prominently in the upcoming proxy season. Part III looks specifically at say-on-pay votes, chronicling both their evolution as shareholder proposals and the issues brought to the fore for the 2012 season in light of ISS’s decision to weigh minority shareholders’ objections to proposed pay packages.

About Proxy Monitor

While scholars have differed markedly in their assessment of corporate governance and the new shareholder activism,[10] there has been limited empirical evidence through which to evaluate the debate. To facilitate research that might shed light on the issue, in 2011, the Manhattan Institute’s Center for Legal Policy launched a new online database, ProxyMonitor.org, the first publicly available resource containing easily searchable and sortable information on public company shareholder proposals. The database initially cataloged proposals dating back to 2008 for the 150 largest companies by revenues; it has subsequently been expanded to include the 200 largest companies, with proposals dating back to 2006.

Through the 2011 proxy season, I authored a series of findings,[11] culminating in a full report in September 2011[12] that made the following observations:

- The new shareholder activism is largely driven by a small subset of shareholders.

- Only a small subset of proposals is likely to receive shareholders’ majority support.

- The type of proposals being introduced has varied significantly over time.

- Shareholder proposals have varied substantially by industry.

- Labor-union funds’ shareholder-proposal activity correlates with union-organizing campaigns.

|

I. Historical Perspective: Shareholder-Proposal Trends over Time

Before turning to the upcoming proxy season in more detail, it is useful to examine briefly the major trends in shareholder-proposal activity at the largest publicly traded American corporations. Drawing from the Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database,[13] this section of the report examines:

a. Who is sponsoring most shareholder proposals

b. How the number of such proposals has varied over time

c. How the approval rates of such proposals have varied over time

d. The types of proposals that have gained particular traction

a. Shareholder-proposal sponsorship

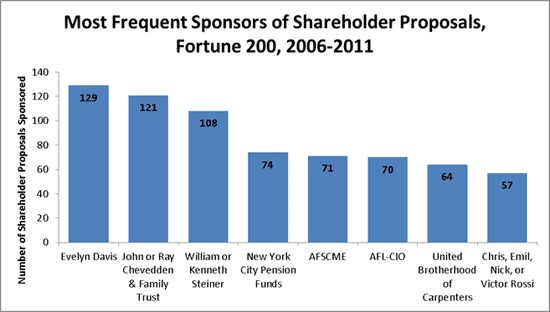

As shown in the graph below, a relatively small number of investors have introduced a large fraction of all shareholder proposals. Across the 200 largest American public companies, over the last six years, the eight shareholders shown have introduced 694 proposals, more than one-third of the total number of proposals introduced.

Four of these investors—Evelyn Davis, John Chevedden, and members of the Steiner and Rossi families—are individual investors who repeatedly file similar proposals across several companies in an effort to influence corporate behavior. Commonly called “corporate gadflies,”[14] these four investors, as I documented in earlier research,[15] have historically focused their proposals on procedural rules designed to increase shareholder voting power; all told, they have sponsored over two-thirds of all shareholder proposals introduced by individual investors.

Four of these investors—Evelyn Davis, John Chevedden, and members of the Steiner and Rossi families—are individual investors who repeatedly file similar proposals across several companies in an effort to influence corporate behavior. Commonly called “corporate gadflies,”[14] these four investors, as I documented in earlier research,[15] have historically focused their proposals on procedural rules designed to increase shareholder voting power; all told, they have sponsored over two-thirds of all shareholder proposals introduced by individual investors.

The other four most regular sponsors of shareholder proposals are pension funds related to public and private labor unions: New York City public employees; the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (“AFSCME”); the AFL-CIO; and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters. As I documented in earlier research,[16] these investors have particularly focused their efforts on proposals related to executive pay or chairman independence—matters acutely sensitive to management—and they have particularly targeted companies in industries facing prominent union-organizing campaigns.

The two-thirds of shareholder proposals backed by investors other than these eight have largely been sponsored by other institutional investors tied to organized labor or investing with a specific social, policy, or religious orientation—with other institutional investors essentially absent from the process. As I have previously documented,[17] fully 98 percent of all shareholder proposals in the period studied were introduced by labor or social funds or by individual investors.

b. Number of shareholder proposals

b. Number of shareholder proposals

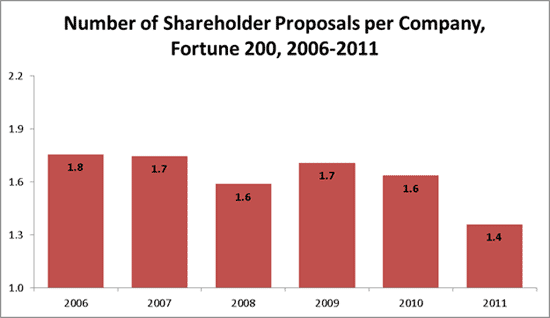

As shown in the graph below, the number of shareholder proposals introduced has remained fairly constant in recent years. The number of proposals introduced per company varied from 1.6 to 1.8 from 2006 through 2010, before declining modestly to 1.4 in 2011. The decline in proposals in 2011 is largely attributable to the absence of shareholder proposals seeking a shareholder advisory vote on executive compensation, given that such proposals are now required under Dodd-Frank. (For a fuller discussion of the history of say-on-pay shareholder proposals, see Part III below.)

c. Shareholder-proposal approval rates

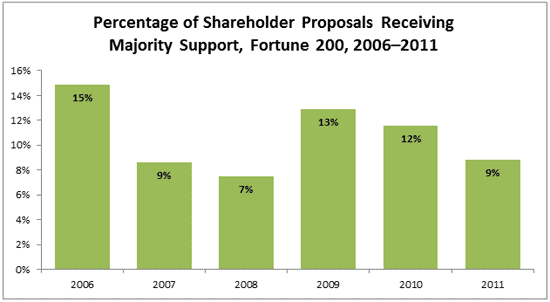

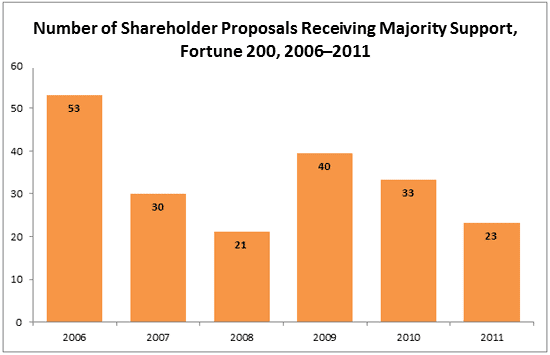

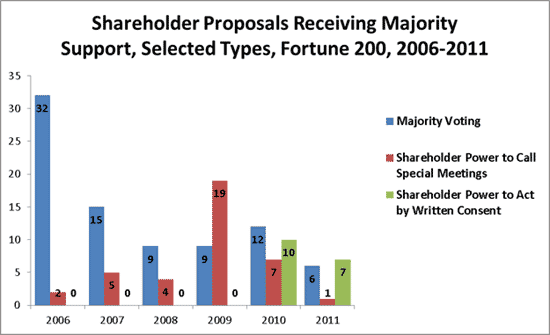

In contrast to the rate of introduction of proposals, their rate of shareholder proposal passage has varied significantly, as shown in the graphs below. For example, more than twice as many proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders in 2006, as compared with 2008, in both absolute and relative terms. Explaining this variation requires a particularized look at the actual shareholder proposals winning majority support, as explored in subsection (d) below.

d. Types of proposals garnering shareholder support

To explore the variation in shareholder approval rates, I looked at individual proposal data, which, over the expanded time series data set, show that the variation is mostly explained by the waxing and waning of a small number of proposals that are much more likely to pass than most others: “majority voting” rules; proposals to allow shareholders to call special meetings; and proposals to allow shareholders to act by written consent.

Majority voting. That 15 percent of shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders in 2006 is largely attributable to the prominence, and relatively high approval, of proposals requiring a majority of shareholder votes to elect directors. Thirty-two of the 53 proposals approved in 2006, and 83 of the 200 proposals approved over the six years studied, related to majority voting. Predictably, as majority-voting rules became more widely adopted and emerged as a norm for large public companies without substantial insider holdings, fewer such proposals were introduced, and shareholder approval rates fell overall.

Majority voting. That 15 percent of shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders in 2006 is largely attributable to the prominence, and relatively high approval, of proposals requiring a majority of shareholder votes to elect directors. Thirty-two of the 53 proposals approved in 2006, and 83 of the 200 proposals approved over the six years studied, related to majority voting. Predictably, as majority-voting rules became more widely adopted and emerged as a norm for large public companies without substantial insider holdings, fewer such proposals were introduced, and shareholder approval rates fell overall.

Special meetings. Proposals to allow a certain percentage of shareholders to call a special meeting drove a second increase in shareholder approval rates beginning in 2009, when such proposals began to be approved in larger numbers. The large increase in the adoption of such proposals in that year, however, was not sustained: after 19 such proposals were adopted in 2009, only seven passed in 2010, and only one in 2011. In total, 38 of the 200 successful proposals over the period studied related to shareholders’ power to call special meetings.

Written consent. Shareholder powers to act by written consent are common in smaller, privately held companies but, until recently, were not on the corporate governance agenda for large, publicly traded corporations. That changed in 2010, when such proposals began to be introduced, and approved, in significant numbers. It is too soon to tell whether the initial success of such proposals will be sustained or prove transitory, as with special meeting rules; the number of such proposals approved did fall from 2010 to 2011.

In total, process-based reforms such as majority-voting requirements and shareholder power to call special meetings and act by written consent constituted over two-thirds of all shareholder proposals to gain majority backing over the period studied.

While these proposals may seem relatively uncontroversial, they are not without significance, and their merits are debatable. One consequence of majority-voting requirements is to make directors much more sensitive to “withhold vote” attacks on their election, thus empowering shareholder activism more broadly. Shareholder power to call a special meeting, particularly if granted to shareholders with relatively small stakes, may empower minority shareholders to gain voice in setting corporate agendas—arguably, at the expense of a shareholder majority. Similarly, shareholder authority to act by written consent may empower activist shareholders by facilitating their ability to effect change in corporate rules or behavior without allowing management a full, considered response.

II. What to Watch for in 2012: Shareholder Proposals

As discussed at the outset, in 2012 I will be closely following proposals calling for: (1) disclosure or shareholder regulation of corporate political spending and lobbying; (2) “proxy access,” or the ability of shareholders to place their own nominees for directors on corporate proxy ballots; and (3) “chairman independence,” i.e., requiring that the chairman and chief executive officer position be separated. I discuss each briefly in turn.

1. Political Spending

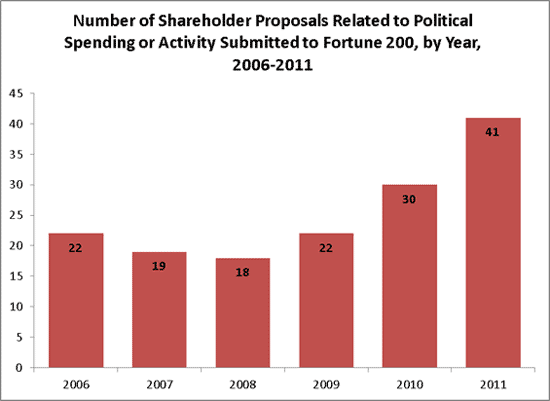

Background. From 2006 through 2009, shareholder proposals related to corporations’ political spending were already relatively common: 18 to 22 such proposals were sponsored on the proxy ballots of Fortune 200 companies each year. Since the Supreme Court’s controversial 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,[18] which held that corporate political speech was protected by the First Amendment, the number of such proposals has escalated markedly—increasing to 30 in 2010 and to 41 in 2011, as shown in the graph below.

Proposals relating to political spending have varied in type, including the following:

Proposals relating to political spending have varied in type, including the following:

- Proposals calling on the independent members of the board of directors to institute a “comprehensive review” of corporate political expenditures and spending processes, including an assessment of approval and oversight processes, to be presented back to shareholders (one example was submitted by Green Century Capital Management to the shareholders of Occidental Petroleum Corporation, and garnered 24.27 percent support).

- Proposals calling for the publication of a semiannual report, posted on the company’s website, on the policies for trade-association membership; indirect expenditures for political purposes; an accounting of such expenses and the title of individuals at the corporation involved in the decision to make such expenses (one example was submitted by Domini Social Investments to the shareholders of the Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., and garnered 12.09 percent support).[19]

- Similar proposals limited to lobbying and grassroots lobbying (one example was submitted by the pension plan of AFSCME to the shareholders of International Business Machines Corporation(IBM), and garnered 28.50 percent support).

- Proposals calling for the company to publish an accounting of all direct and indirect political contributions made in the previous year, five days after shareholder approval, in two national newspapers and leading periodicals in nine American cities (one example was submitted by Evelyn Davis to the shareholders of Pfizer Inc., and garnered 4.63 percent support).

- Proposals calling for the annual publication on the company’s proxy statement of corporate and political action committee policies on political expenditures and electioneering, including an accounting of and rationale for expenses anticipated in the forthcoming fiscal year, and calling for a shareholder advisory vote on such prospective expenses (one example was submitted by Northstar Asset Management to the shareholders of Procter & Gamble Company, and garnered 6.71 percent support).

To date, only one shareholder proposal related to political spending at a Fortune 200 company has received support from a majority of stockholders: a 2006 proposal requiring Amgen to prepare a report on its political spending priorities, sponsored by the Green Century Balanced Fund, a social investing fund. Although Amgen’s board recommended that shareholders vote for that proposal, it still only won the backing of 67 percent of investors. Not a single shareholder proposal related to political spending has received majority shareholder support over management’s objection.

Developments. I expect a continued increase in proposals related to political spending in 2012. Such proposals will be spurred on by the 2012 presidential campaign season, continuing public debate over Citizens United,[20] and renewed congressional efforts to pass the Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections, or DISCLOSE, Act,[21] intended to increase transparency in corporate political spending.[22]

Potentially reinforcing this trend is the shift in policy by ISS toward a general “vote for” recommendation on shareholder proposals related to disclosure of political spending. ISS’s new position may influence at least some institutional investors that had previously opposed such measures to reconsider their position.

Analysis. The plethora of proposals involving the disclosure and shareholder regulation of corporate political spending are varied in type. Furthermore, as I (along with UCLA law professor Stephen Bainbridge and former California commissioner of corporations Keith Paul Bishop) noted in November in comments submitted to ISS, “corporations are not all similarly situated with regard to how various proposals for political disclosure might affect share value,”[23] and a company that is “generally committed to disclosing its political expenditures may nevertheless reasonably object” to at least some classes of these proposals.[24]

Moreover, I am particularly concerned that “some shareholders’ motivations may deviate from increasing share value and thus may not be aligned with the interests of the broader class of diversified shareholders,” particularly since labor funds and socially oriented or religious investors have sponsored 92 percent of all political-spending proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies since 2008. At least some of these proposals “may serve primarily to chill corporate political speech broadly, including on issues that most diversified shareholders—as distinguished from the proposals’ sponsors—might prefer that the corporation’s views be heard.”[25]

2. Proxy Access

Background. In July 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected as “arbitrary and capricious” a rule proposed by the SEC that would have mandated that publicly traded companies list shareholders’ nominees for director on their corporate proxy ballots, as long as the nominating shareholder had held at least 3 percent of a company’s stock for a minimum of three years.[26] The SEC decided not to appeal that decision but instead approved amendments to Rule 14a-8 that permit shareholder proposals seeking proxy access—proposals that had been foreclosed since 2007 while the SEC explored its mandatory rule.[27]

Developments. According to press accounts, at least 15 proposals related to proxy access had been submitted for the upcoming proxy season, with a majority sponsored by activist individual investor Kenneth Steiner and Norges Bank Investment Management, which manages the government workers’ pension funds in Norway.[28] Each of these proposals called upon the company’s board to review how to amend bylaws to grant proxy access, rather than directly amending the bylaws themselves. (More proposals in this area—and more specific, binding proposals including bylaws amendments—could be expected later in 2012, since there was limited time between the SEC’s decision and the deadline for introducing shareholder proposals for the early spring proxy season, given the requirement that such proposals be introduced no fewer than 120 days prior to a company’s annual meeting.)[29]

In February 2012, Hewlett-Packard announced that labor-affiliated Amalgamated Bank had agreed to withdraw its proxy-access proposal and that the company would be advancing its own proposal calling for a bylaw amendment instituting proxy access in 2013.[30] (In 2007, a proxy-access proposal submitted at HP’s annual meeting had garnered the support of 43 percent of shareholders.)

Analysis. By giving dissident shareholders the opportunity to place actual competing candidates on corporate proxy ballots, rather than merely campaigning for “no” votes for existing directors, proxy-access rules, if adopted, could be expected to further strengthen shareholders’ leverage over management. It will be interesting to observe whether most institutional investors welcome this shift or if they, like the D.C. Circuit, will worry about the risk that “unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value, can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value, and will likely cause companies to incur costs even when their nominee is unlikely to be elected.”[31]

3. Chairman Independence

Background. Proposals calling for chairman independence—i.e., having a board chairman distinct from the company’s chief executive officer—have been relatively commonplace. They have been unlikely to pass. Among Fortune 200 companies, only four such proposals have received majority shareholder support since 2006: a 2007 proposal submitted to the shareholders of CVS Caremark by the individual activist William Steiner; a 2009 proposal submitted to the shareholders of Office Depot by a fund affiliated with the AFL-CIO; a 2009 proposal submitted to Bank of America by a fund affiliated with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU); and a 2011 proposal submitted to Aetna by a fund affiliated with United Association of Plumbers, Pipefitters and Sprinklerfitters.

Developments. In 2012, the two most historically active union-related sponsors of shareholder proposals, AFSCME and the New York City government-worker pension funds, have introduced chairman independence proposals, with significant fanfare.[32] Lisa Lindsley, director of capital strategies at AFSCME, said that “the financial crisis shows there hasn’t been enough adult supervision of CEOs” and announced that the union’s pension funds were introducing shareholder proposals on chairman independence at American Express, Anadarko Petroleum, Dean Foods, Goldman Sachs, Johnson & Johnson, JPMorgan Chase, Northern Trust, and Lockheed Martin.[33] New York City comptroller John Liu, who oversees the city’s pension funds, announced that the New York funds were sponsoring shareholder proposals related to chairman independence with at least three companies, stating that CEOs who also serve as chairmen “can compromise a board’s ability to carry out its most fundamental responsibility, which is to independently oversee management.”[34]

Analysis. Notwithstanding Liu’s assertions and those of other supporters of these proposals, there is an absence of empirical evidence confirming the claim that corporations governed by joint chairmen-CEOs underperform their peers that separate the functions. Several large companies have combined the roles at some point in their history, including top performers like Microsoft (Bill Gates) and Berkshire Hathaway (Warren Buffett).[35]

It’s worth noting that the prominent role being played by labor-union funds in backing proposals for chairman independence is nothing new: as I have documented in earlier research, a majority of these proposals have historically been sponsored by labor-affiliated investors.[36] Like proposals related to executive compensation, those calling for chairmen-CEOs to give up day-to-day control of the company or take, in effect, a boss on the board of directors, are “highly sensitive for corporate leaders, [and] labor’s role in backing this class of proposals raises the prospect that unions are attempting to leverage the shareholder-proposal process to gain negotiating position over management.”[37] Such a prospect is amplified by the fact that each of the chairman-independence proposals passed to date has been in the retail or financial-services sector, which, as I noted in my 2011 report, are both significantly more likely to be targeted by labor-backed shareholder proposals and the targets of ongoing labor-organizing campaigns.[38] In keeping with this trend, five of the nine companies being targeted by AFSCME in 2012 are in these two industrial sectors.

III. What to Watch for in 2012: Say on Pay

Apart from shareholder proposals, those interested in corporate governance should pay particular attention in 2012 to the evolution of say-on-pay advisory votes, in the second year of such votes mandated under Dodd-Frank.

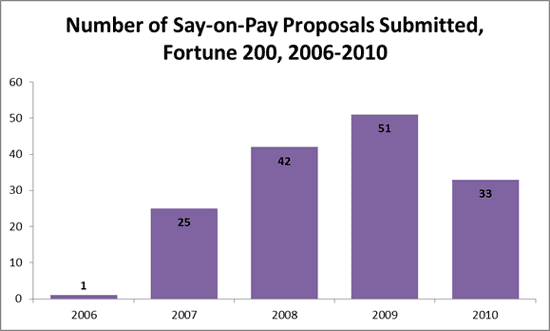

Background. Although now the law of the land, shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation were essentially unknown in American corporate governance prior to 2006, when, drawing on practice in the United Kingdom, the concept began to be introduced in shareholder proposals.[39] As shown in the graph below, one such proposal was introduced in 2006; but the number grew quickly: by 2009, 51 of the Fortune 200 companies faced a say-on-pay proposal on their annual meeting proxy ballots.

Only a small fraction of these say-on-pay proposals passed—peaking at eight of the 51 proposals in 2009.

Only a small fraction of these say-on-pay proposals passed—peaking at eight of the 51 proposals in 2009.

Developments. Notwithstanding the general investor rejection of the say-on-pay vote, Congress enshrined the rule into federal law in the 2010 Dodd-Frank reform.[40] In 2011, virtually every large public company held an advisory vote on shareholder compensation. Only a very small share of proposed executive pay packages were voted down by shareholders in the first full year of say on pay—including the plans of only three of the 200 largest companies.

But just as the failure of most say-on-pay proposals to receive majority-shareholder backing did not prevent their ultimate mandate by Congress, the fact that the overwhelming majority of pay plans were approved by a majority of shareholders may not limit such pay votes’ impact. In fall 2011, ISS announced its intention to challenge management to respond whenever 30 percent or more of shareholders voted against management’s proposed executive compensation plan, even if a majority of shareholders approved.[41]

Analysis. As I noted in an earlier report, “the first year of mandatory say-on-pay throws into question the rationale for the new rule.”[42] Executive pay in 2011 rose markedly (as much as 23 percent, according to some reports)[43] and received broad shareholder support. Thus, “[e]ither such pay packages are not actually destructive of share value, as CEO pay critics claim, or the shareholder-proxy process would seem to be an ineffective means of moderating executive compensation.”[44]

More significant than shareholder votes on executive pay is the new ISS policy, which, if heeded by shareholders, runs the risk of empowering minority investors who may take issue with executive pay in the proxy process for reasons unrelated to share value. In particular, labor-union pension funds might choose to attack executive pay proposals for union-related interests actually adverse to most shareholders:

[In 2011,] the Association of State, County, and Municipal Employees actively campaigned against the pay packages at five [Fortune 150] companies—Alcoa, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer—and four of these received under 70 percent shareholder support for their executive-compensation plans. (Alcoa received over 84 percent support, but only after modifying its proposed plan in reaction to labor complaints.)

Such labor involvement is concerning in light of the finding by the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Labor (OIG), in March 2011, that it could not rule out the possibility that the managers of labor pension plans were using “plan assets to support or pursue proxy proposals for personal, social, legislative, regulatory, or public policy agendas, which have no clear connection to increasing the value of investments used for the payment of benefits or plan administrative expenses.”[45]

Given my previous findings that labor pension funds have been more likely to target companies in industries facing ongoing labor-organizing campaigns,[46] we should watch with particular care the companies whose executive pay plans are being targeted by organized labor in 2012.

Conclusion

The trend of increased activism through shareholder proposals submitted in the annual proxy process for publicly traded corporations has significant policy implications. Issues of public concern, such as corporate spending on the political process, are being pursued through a corporate-governance process traditionally focused on maximizing returns to shareholders.[47]

Even apart from substantive topics like corporate political speech, many of the most significant shareholder proposals relating to corporate governance rules arguably empower minority blocks of shareholders whose interests, like those of labor-union pension funds, may be adverse to the broader class of a company’s equity ownership. And if a sufficient number of institutional investors follow the guidance of ISS regarding executive pay plans that receive majority shareholder support, but sizable minority dissent, labor unions and other minority investors may be empowered to pursue their agenda vis-à-vis corporate management by threatening to target executive pay in the annual proxy season.

Endnotes

- 130 S. Ct. 876 [hereinafter Citizens United].

- See id.

- See Louis Lehot & John D. Tishler, Amendments to SEC Rule 14a-8 Allowing Shareholder Proposals for Proxy Access Regimes to Come into Effect, Natlawreview.com. (Sept. 13, 2011), http://www.natlawreview.com/article/amendments-to-sec-rule-14a-8-allowing-shareholder-proposals-proxy-access-regimes-to-come-eff.

- See Joann S. Lublin & Ben Worthen, H-P Activist Investors Make Proxy Progress , Wall St. J., Feb 6, 2012, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204662204577201743734220890.html?KEYWORDS=proxy.

- See James R. Copland, Proxy Monitor 2011: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism 16-17 (Manhattan Inst. for Pol'y Res., Fall 2011), available at http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/pmr_02.aspx.

- See Ross Kerber, AFSCME Eyes Dual Chairman-CEO Roles At JPMorgan, Goldman, Huffington Post (Jan. 17, 2012), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/17/afscme-chairman-ceo-roles_n_1209924.html.

- Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 §951 (2010) [hereinafter Dodd-Frank Act]; 17 C.F.R. § 229.402 (2011).

- See Copland, supra note 5, at 13.

- See ISS, 2012 U.S. Proxy Voting Summary Guidelines 38, January 31, 2012, available at http://www.issgovernance.com/files/2012USSummaryGuidelines1312012.pdf (recommending that investors “[v]ote AGAINST or WITHHOLD from the members of the Compensation Committee and potentially the full board if . . . [t]he board fails to respond adequately to a previous MSOP proposal that received less than 70 percent support of votes cast”).

- Some academic researchers, most prominently Harvard’s Lucian Bebchuk, have generally praised expansions of the shareholder-proposal process, arguing that shareholders have inadequate rights vis-à-vis the corporation and that high agency costs limit equity owners from enforcing their interests against corporate management. See, e.g., Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Case for Increasing Shareholder Power, 118 Harv. L. Rev. 833 (2005) Others, notably UCLA’s Stephen Bainbridge, have argued that shareholders’ interests are adequately protected by their ability to sell their shares and sue for breaches of fiduciary duty, and worry that expanding shareholder voting rights could lead to politicized outcomes that hurt share value by interfering with business judgment better delegated to professional managers overseen by boards of directors. See, e.g., Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 547 (2003).

- See Copland, New Findings, ProxyMonitor.org., http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx (last visited Feb. 13, 2012).

- See Copland, supra note 5.

- In my Fall 2011 Proxy Monitor report, Copland, supra note 5 , I examined many of these questions based on the then-existing Proxy Monitor dataset, limited to the Fortune 150 companies, from 2008 through 2011. While I have not yet replicated each of the statistical tests conducted in the full 2011 report, preliminary observations tend to confirm the 2011 findings, in addition to the further insights discussed herein.

- For an academic article employing the term, see Charles M. Yablon, Overcompensating: The Corporate Lawyer and Executive Pay, 92 Colum. L. Rev. 1867, 1895 (1992). See also Jessica Holzer, Firms Try New Tack Against Gadflies, Wall St. J., Jun. 6, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304906004576367133865305262.html.

- See Copland, supra note 5, at 7.

- See id. at 8, 10-12, 17.

- See id. at 7-8.

- Citizens United, supra note 1.

- Vote totals for Goldman Sachs include counting abstentions as “no” votes, in keeping with that company’s practice. Among other companies listed, abstentions are counted at Occidental Petroleum but not counted at IBM, Pfizer, and Procter & Gamble.

- Citizens United, supra note 1.

- H.R. 5175, 111th Cong. (2nd Sess. 2010).

- See Sam Stein, Disclose Act: Super PAC Transparency Legislation to Be Introduced by House Democrats, Huffington Post (Jan. 25, 2012), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/25/disclose-act-super-pac-chris-van-hollen_n_1232008.html.

- Stephen Bainbridge, Keith Paul Bishop & Copland, Comment, on Proposed Change in ISS Policy on Political Spending (November 7, 2011), http://www.issgovernance.com/files/Comment-40.pdf.

- Id.

- Id.

- The adopting release is published as Facilitating Shareholder Director Nominations, SEC Rel. No. 34-62764 (Aug. 25, 2010), available at http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2010/33-9136.pdf, see also 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-11 (2011).

- See Abigail Caplovitz Field, Proxy Access Debate Far from Over,CorporateSecretary.com., (Sept. 9, 2011), http://www.corporatesecretary.com/articles/proxy-voting/12000/proxy-access-debate-far-over/.

- See Field, What the New Proxy Access Rules Mean for You ,CorporateSecretary.com., (Feb. 1, 2012), http://www.corporatesecretary.com/articles/proxy-voting/12139/what-new-proxy-access-rules-mean-you/.

- See id.

- See Ronald Barusch, Dealpolitik: Is H-P Setting a Trend for Proxy Access?, Wall St. J., Feb 7, 2012, http://blogs.wsj.com/deals/2012/02/07/dealpolitik-is-h-p-setting-a-trend-for-proxy-access/.

- Business Roundtable & Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. SEC, at 14 (D.C. Cir. July 22, 2011), available at http://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/89BE4D084BA5EBDA852578D5004FBBBE/$file/10-1305-1320103.pdf.

- See Kerber, supra note 6.

- Id.

- Id.

- Gates served as Microsoft’s chairman of the board as well as its president or chief executive officer, managing the company’s operations, from the time of its incorporation in Washington on June 25, 1981 through January 13, 2000, when he stepped down as CEO. See Joe Wilcox, Michael Kanellos & Aimee Male, Gates Turns Over Reins of His Empire, CNET News, Jan. 13, 2000, http://news.cnet.com/2100-1001-235639.html. Buffett has served as chairman and CEO at Berkshire Hathaway since 1970.

- See Copland, supra note 5, at 19.

- Id.

- See id.at 9-11.

- See Fabrizio Ferri & David Maber, Say on Pay Votes and CEO Compensation: Evidence from the United Kingdom (Oct. 15, 2010) (unpublished manuscript), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1420394.

- Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 7.

- See ISS, supra note 9, at 38.

- Copland, supra note 5, at 13.

- See Pradnya Joshi, We Knew They Got Raises. But This?, N.Y. Times, Jul. 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/03/business/03pay.html?pagewanted=all.

- Copland, supra note 5, at 13.

- OIG Department of Labor Report, Proxy-Voting May Not Be Solely for the Economic Benefit of Retirement Plans, Rpt. No. 09-11-001-12-121, intro (March 31, 2011), http://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2011/09-11-001-12-121.pdf.

- See Copland, supra note 5, at 9-11.

- See id. at 9-11.