PROXY MONITOR

REPORT

Fall 2011

A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism

SUMMARY

This report reveals that in recent years, activist groups, including labor unions, are exploiting the shareholder proposal process to exert influence over corporate management and to pursue policy goals in an end run around the legislative process.

Copland's analysis draws upon information from the recently expanded ProxyMonitor.org shareholder proposal database of all Fortune 150 companies (January 2008 to August 2011.) Copland suggests that activists are reshaping American corporate governance both directly and by influencing legislation such as the new shareholder votes mandated by "say-on-pay" in Dodd-Frank. He finds that special interests may be gaining leverage over management, and there is reason to believe that these activists' agendas might be adverse to the interests of the typical diversified shareholder.

PRESS RELEASE

EVENT

At a forum in New York, James Copland presented his new report to media and industry insiders. The event also featured a panel discussion on trends in shareholder activism including: William Allen, professor of Law and Ethics at NYU; Stephen Brown, director of corporate governance at TIA-CREF; Shelley J. Dropkin, deputy corporate secretary & general counsel for Citigroup, Inc.; John Siemann, president and partner of Phoenix Advisory Partners; Lori Zyskowski, corporate and securities counsel for General Electric. View event video.

PODCAST

Harvey Pitt, former chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and James Copland discuss shareholder proposal trends over the last four years and how the SEC has changed since Dodd-Frank. Listen to their discussion.

OP-ED

Political activism meets corporate governance, James Copland, Washington Examiner, 9-21-11

SELECT MEDIA COVERAGE

Calpers and Calstrs launch diversity drive, Financial Times Online, 9-27-11

Corporate Governance/Shareholder Activism, RealClearMarkets.com, 9-23-11

Report: Shareholder Activists Abuse Dodd-Frank Regs, Daily Caller, 9-21-11

Study Says Majority of Shareholder Proposals Submitted by Four Individuals, Their Affiliates, BNA's Daily Report for Executives, 9-21-11 (subscription only)

RADIO

WABC's "John Batchelor Show," 9-29-11

SBA's "Small Business Advocate," 9-26-11

Executive Summary

In recent years, a small number of activist shareholders have increasingly sought to use their equity stock holdings to exert influence over business management. Proponents of “shareholder democracy” have successfully pushed shareholder proposals offered for votes at the annual meetings of public corporations that change the manner in which directors are elected and in which shareholders can force corporate action outside those annual meetings. Proponents of “corporate social responsibility” have pushed companies to change their behavior with a clear interest in pursuing policy goals rather than share-price maximization. Critics of management’s pay levels have pushed for shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation—a practice borrowed from Britain but unheard of in the United States a decade ago—and such “say on pay” votes are now mandated under federal law by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010.

Academics and investors alike have debated shareholder activism generally and these proposals specifically; but to date, hard data have generally not been publicly available about this phenomenon. To fill in this informational gap and to uncover and analyze trends in this aspect of shareholder activism and its influence over corporate governance, the Manhattan Institute launched its Proxy Monitor project. The ProxyMonitor.org database assembles information on the 150 largest corporations (by revenues, as ranked by Fortune magazine) and currently includes searchable and sortable information on every shareholder proposal submitted at each company from 2008 through August 1, 2011. (Earlier years’ proposals, and a broader data set of companies, will be added to the database in the months ahead.)

This report is an early analysis drawn from the database as of the end of the 2011 proxy season. Among its key findings:

- Shareholder proposals are sponsored by a small subset of shareholders. The overwhelming majority of shareholder proposals since 2008—98 percent—were offered by three very specific types of stock owner:

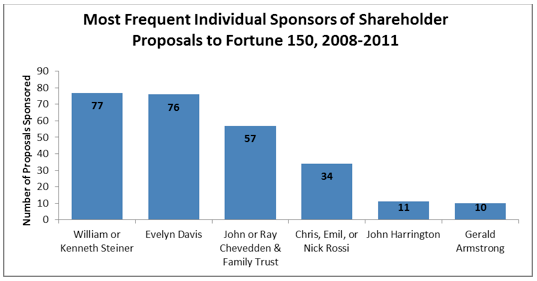

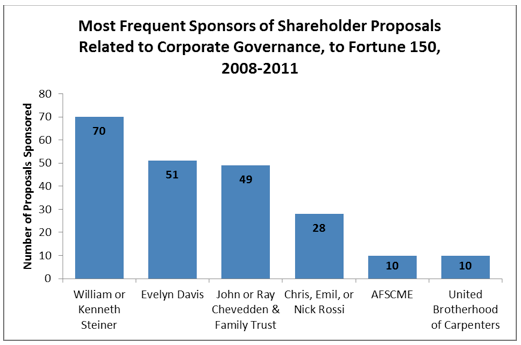

- A small number of individuals widely known as “corporate gadflies”—small investors who provoke management by repeatedly filing multiple substantially similar shareholder proposals at many companies (more than two-thirds of all proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies by individual investors came from Evelyn Davis and members of the Steiner, Chevedden, and Rossi families).

- Pension funds and other investment vehicles affiliated with labor unions, in both the public and private sectors.

- Social investment vehicles affiliated with religious organizations or public policy groups, or otherwise organized as social-interest funds focused on policy goals other than share-price maximization.

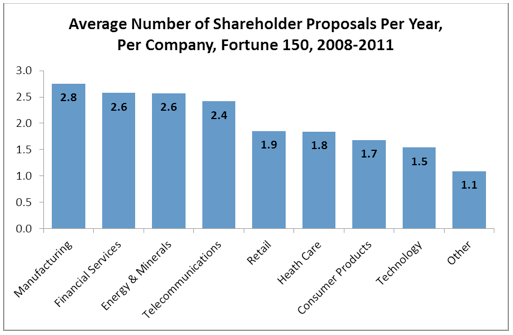

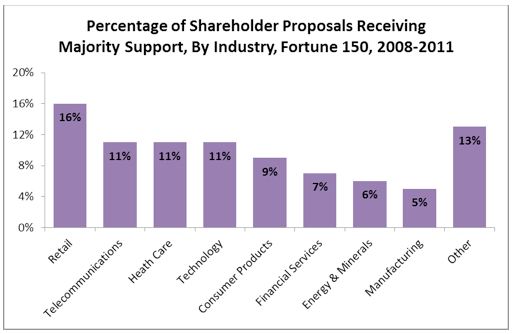

- Different industries face different levels of shareholder activism. Manufacturing companies dealt with nearly twice as many shareholder proposals as did technology companies during the study period. Energy and financial-services companies also face more proposals than do companies in other sectors. Shareholder proposals were more likely to pass in the retail sector than in others.

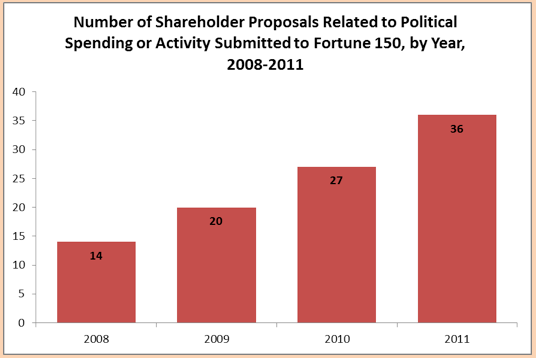

- The types of shareholder proposals introduced vary over time.Proposals related to executive compensation fell markedly in 2011, after advisory shareholder votes on management pay plans and golden parachutes were mandated in Dodd-Frank. Proposals seeking to authorize shareholders to act outside of annual meetings by written consent were first introduced in 2010, and their numbers increased in 2011. Proposals seeking social or policy goals vary in type, based on the broader political discourse—often involving “health-care principles” during the debates over federal health-insurance reform and increasingly involving corporations’ political spending in the wake of the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

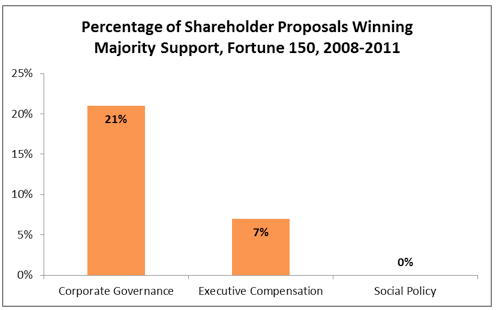

- Success rates of shareholder proposals vary greatly according to subject.In the study period, 21 percent of proposals related to general process-based corporate-governance concerns passed, but only 7 percent of those on executive compensation succeeded. None of the proposals related to social or policy goals, including proposals relating to corporations’ political spending, were supported by a majority of a company’s shareholders.

- Labor unions’ shareholder activism appears potentially linked to union organizing campaigns and motivated by concerns other than shareholder return. Labor-affiliated funds disproportionately introduced shareholder proposals at companies that are in industrial sectors publicly targeted by union organizing campaigns. Labor-affiliated funds’ shareholder proposals also tend to focus on executive compensation and the separation of the chairman and CEO position for companies—management-sensitive topics that potentially signal an effort to use the shareholder-proposal process as leverage over management to the benefit of union workers rather than in the interests of the broader class of shareholders.

On balance, the empirical evidence analyzed in this report tends to throw into question the push for “shareholder democracy” and suggests that shareholder activism in the form of shareholder proposals submitted on the proxy ballots of publicly traded companies may be more a vehicle for interest-group capture of corporations rather than for mitigating agency costs and improving shareholder returns. Further studies are necessary, however, to solidify this conclusion.

In recent years, publicly traded American companies increasingly have found themselves confronted by shareholders who want to influence corporate management[1]. Simultaneously, the federal government has sought more influence over corporations by increasing its role in the enforcement of corporate law, first through the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley reforms[2] (enacted in the wake of the collapsed Internet stock bubble and frauds at Enron and other large companies), and second through the 2010 Dodd-Frank measures[3] enacted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The new federal rules have themselves empowered shareholders and reinforced a particular form of shareholder activism, namely, proposals submitted by shareholders at the annual meetings of publicly traded corporations.

The rise of such activism has been praised by some scholars and investors but excoriated by others[4]. Their ongoing debate has raised new theoretical arguments but has offered little empirical analysis of actual activity by shareholders[5]. Basic factual questions have gone unanswered: Who are the shareholders involved in shareholder activism? What do they propose, and whom do they target? How, if at all, do their proposals benefit shareholders at large?

To fill this gap, the Manhattan Institute launched the Proxy Monitor project, to uncover and analyze actual trends in shareholder-proposal activity and its influence over corporate governance. The ProxyMonitor.org database assembles information on the 150 largest publicly traded American corporations by revenues, as ranked by Fortune magazine, including searchable and sortable information on every shareholder proposal submitted at each company from 2008 through August 1, 2011. Thus, the data for 2011 cover all Fortune 150 companies that mailed proxy materials in advance of an annual meeting, or that held such a meeting, as of August 1. Because most corporations hold their annual meetings between mid-April and mid-June, the data set includes most companies: shareholder proposals for 134 of the Fortune 150; and voting results for 133.

This report is an early analysis drawn from information contained in the database. We have used the information to create an empirical assessment of current shareholder activity as it relates to corporate governance, with a focus on revealing:

- Who is driving shareholder activism—i.e., who are the most frequent sponsors of shareholder proposals?

- Where is shareholder activism focused—i.e., which companies and industries are being targeted with shareholder proposals?

- What is the subject of shareholder activism—i.e., what are the principal agendas being advanced through shareholder proposals?

The database reveals that most shareholder activism is sponsored by very few investors: a subset tied to organized labor, religious institutions, and “social investing” funds sponsors most proposals. The rest comes from a handful of “corporate gadflies,” small investors who provoke management by repeatedly filing multiple substantially similar shareholder proposals at many companies. Institutional investors outside the social-investing sector largely eschew the shareholder-proposal process. This pattern, along with early returns on Dodd-Frank-mandated advisory votes on executive pay, suggests that much of today’s shareholder-proposal activity is, at best, loosely related to most shareholders’ financial interests

Background

Traditionally, corporate law in the United States has largely resided at the state level. In the Great Depression, Congress enacted an overarching federal regulatory regime, through the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934[6], but the federal role was largely oriented toward corporate disclosure. Substantive corporate-law rules and processes were still governed by the states.

In the 1970s, the federalist structure of corporate law came under attack from academics who argued that allowing corporations to choose their state of incorporation—and thus the state law that regulated corporate-governance issues—created a “race to the bottom” effect that enabled management to exploit shareholders. Corporations, the argument ran, gravitated to a single state, Delaware, because its rules were the most indifferent to shareholders’ interests.[7]

A counterargument, raised initially by Yale law professor Ralph Winter (now of the Second Circuit United States Court of Appeals), argued that, conversely, the federalist structure of corporate law created a “race to the top,” since investors would demand a premium to compensate them for legal rules adverse to their interests, thus raising a corporation’s cost of capital if it chose to incorporate in a state hostile to investors.[8] The fact that corporations could choose to leave Delaware—as they had left New Jersey in the early twentieth century, after Governor Woodrow Wilson tried to leverage the state’s dominance as the site of companies’ incorporation for antitrust enforcement—is, under this theory, viewed as an asset rather than a defect of the corporate-law regime. It is supposed to be part of what makes such a regime superior to a single, national framework.[9]

Though scholars did not agree, the very fact of the debate had an effect. It opened corporate law and corporate culture to the notion that traditional federalist corporate regulation might be inadequate to protect shareholders from “agency costs”—management activity contrary to their interests (see sidebar: Why Stock Equity Ownership?).

As the academic debate raged, private enterprise was also taking aim at agency costs, via a wave of corporate takeovers in the 1980s.[19] Private equity firms and other public companies offered a premium price to existing shareholders to gain control of a majority of public corporations’ stock, and then exercised their voting rights to oust existing management and boards. Companies thought to be bloated were broken up into smaller pieces, and others’ operations were downsized or their management approaches substantially modified. Corporate management largely fought such takeover measures; but in the aggregate, they seemed to add substantially to share value, based on stock-market performance.[20]

Following on the heels of the 1980s takeover movement—largely predicated upon using a “stick” to reduce agency costs—corporate boards began to experiment with “carrots,” by modifying executive-compensation structures better to align management’s incentives with those of shareholders. For example, boards of directors began to experiment with stock options and other equity-compensation plans that transferred some portion of companies’ ownership to chief executives and other top management, in lieu of cash compensation.[21] Moreover, boards began to offer “golden parachutes” and other vehicles that would pay executives in the event of a change of corporate control, so that managers would be active partners rather than impediments to a company’s prospective sale that offered sizable rewards to shareholders.[22]

Why Stock Equity Ownership?

The rise of modern capitalism is largely associated with the emergence of the joint stock corporation in Holland and Britain.[10] Equity capital enables entrepreneurs undertaking risky ventures to raise funds from dispersed sources, who maintain limited liability for the ventures’ losses, without placing any obligation on the entrepreneurs to pay funders an immediate or regular cash flow. Public stock exchanges further facilitate capital formation by enabling equity investors to exit their investments easily and by allowing founder-entrepreneurs to liquidate and diversify themselves, as well as to turn over corporate management to successor leaders.

Equity investors are, by definition, entitled to a corporation’s residual earnings.[11]But because corporate dividend payments are discretionary rather than mandatory and because equity investors are otherwise unable to protect their interests contractually, owners of common stock face significant agency costs, or obstacles to enforcing their interests against corporate management. Absent additional protections for equity owners, managers may choose to pay themselves salaries that deplete the residual earnings available to shareholders. Management may choose to avoid risks that investors might prefer they take. Corporate managers may also choose to avoid choices that imperil their own interests—such as selling the company to a prospective acquirer—even if such choices would create value for shareholders[12].

To protect against these agency costs, owners of equity shares have traditionally been aided by common law “fiduciary duties.”[13] Among these are a duty of loyalty, prohibiting management self-dealing;[14] and a duty of care, obligating managers to handle corporate affairs prudently[15] (though courts typically afford management significant discretion in the exercise of business judgment).[16] Moreover, shareholders are protected by their voting rights—chiefly, the ability to elect directors who oversee management and enforce fiduciary duties.[17] Thus, equity shareholders are protected by their ability to exit (i.e., to sell their shares), their ability to vote (i.e., to throw out directors who are insufficiently protecting their interests), and their ability to sue (i.e., to enforce fiduciary duties through judicial action).

While agency costs are real, corporate legal rules have traditionally avoided other ownership costs inherent in other organizational structures (chiefly, conflicts of interests that arise among various owners) by orienting corporate managers’ fiduciary duties around a single objective of share value.[18] That the corporate form so predominates for large entities suggests that traditional equity ownership oriented around share-value maximization is advantageous in reducing such conflicts. |

As the stock market continued to rise rapidly in the 1990s, many corporate managers made large gains on their stock option plans, even if their companies’ relative performance was middling.[23] A new wave of academic commentary argued that rather than mitigating agency costs, executive-compensation plans were magnifying them by transferring shareholders’ wealth to managers without realizing appreciable benefits in return.[24] Some commentators argued for a shift from shareholder to “stakeholder” capitalism,[25] or for a renewed focus on “corporate social responsibility,”[26] changing the traditional alignment of fiduciary duties exclusively with shareholders’ interests. Others, such as Harvard Law School’s Lucian Bebchuk, have pushed for an increased “shareholder democracy,”[27] arguing that boards of directors were complicit with management and asserting that expanding shareholder voting rights over boards would rein in management abuses and increase shareholder value.

In short, in recent decades both government (with regulation) and the private sector (with its carrots and sticks) have been willing to rewrite corporate rules in the name of “shareholder rights,” and some of the private sector’s efforts in this direction have provoked further arguments for government regulation of corporate management.

These political, cultural, and legal changes combined to encourage use of a device known as the shareholder proposal: stockholders who have owned at least $2,000 in shares for at least one year can place items on a company’s proxy ballot—submitted to all shareholders in advance of annual meetings—for a vote.[28] Whether such measures are appropriate is determined by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC);[29] the substantive rights governing such measures and how they can force boards to act remain largely a question of state corporate law.[30]

Critics of shareholder democracy generally, and of these shareholder proposals specifically, have argued that they are subject to capture by particular interest groups whose priorities are not the interests of their fellow investors.31 For example, in March 2011, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. Department of Labor released a report noting that it could not rule out the possibility that the managers of labor pension plans were using “plan assets to support or pursue proxy proposals for personal, social, legislative, regulatory, or public policy agendas, which have no clear connection to increasing the value of investments used for the payment of benefits or plan administrative expenses.”[32]

Notwithstanding these skeptics, Congress has taken steps over the last decade that expand shareholder voting rights as part of its assertion of a greater federal role in corporate governance, first through the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley reform and second through the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform.

Empirical Analysis

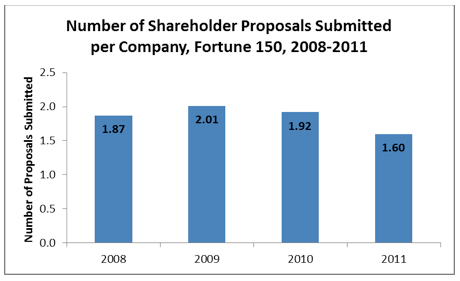

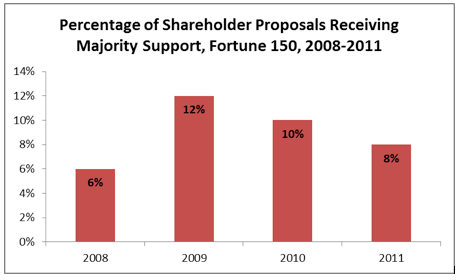

This report assesses empirically all shareholder proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies from 2008 to the present. Proposal activity has held rather steady over the time period—picking up slightly in 2009 and decreasing somewhat in 2011. The percentage of shareholder proposals gaining the support of at least 50 percent of shareholders, however, has varied markedly over the time period, doubling from 2008 to 2009, before declining each year thereafter.

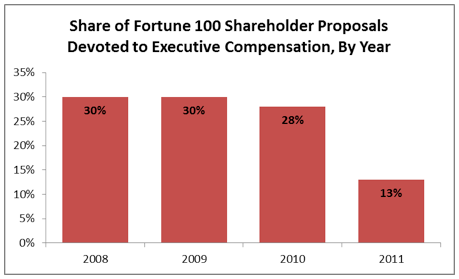

The most probable explanation for the modest decline in the number of shareholder proposals sponsored in 2011 lies in the 2010 passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which, in Section 951, mandates that all publicly traded corporations submit their executive-compensation plans to shareholders for an advisory vote.[33] Because such “say on pay” proposals had been among the most sponsored shareholder proposals in previous years, the new law has likely caused a decline in the sheer number of proposals by obviating the need for this particular proposal type.

There are other drivers of variation from year to year. Success is one: ideas that win proxy votes and are adopted by boards are no longer germane for those corporations, and some of the more successful proposal types may be adopted without a vote of shareholder support at other corporations, precluding the need to introduce them as shareholder proposals. Shareholders may also learn by experience, modifying their proposals or focusing their efforts on those more likely to pass. And, of course, fluctuations in stock-market performance might affect shareholder behavior—both by encouraging a shift in the nature of proposals sponsored and by changing shareholders’ receptiveness to certain classes of proposal.

A closer look at the data offers clear answers to questions about who the shareholder activists are, which companies and industries they target, and the subject matter of their proposals.

a. Who is driving shareholder activism?

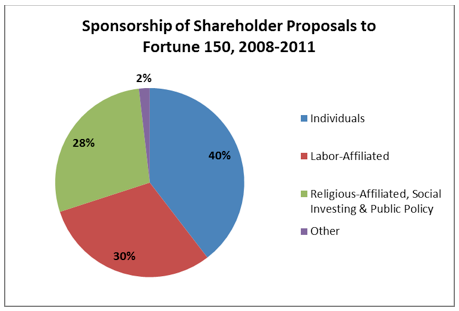

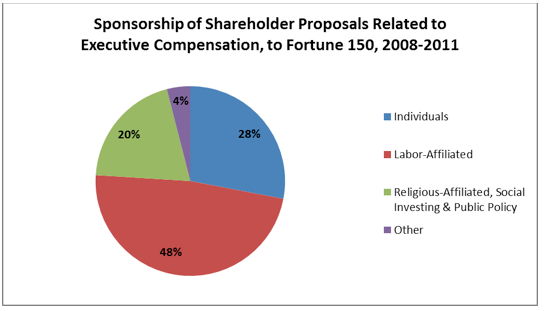

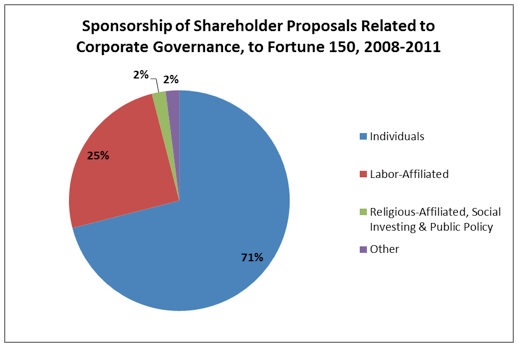

Since 2008, 98 percent of all shareholder proposals submitted to Fortune 150 corporations have been sponsored by three subsets of shareholders:

- A small number of individual “corporate gadflies”;

- Pension funds and other investment vehicles affiliated with labor unions, in both the public and private sectors; and

- Investment vehicles affiliated with religious organizations or public policy groups, or otherwise organized as “social investment” funds, with express interests beyond mere share-price maximization.

The dearth of proposals filed by large institutional investors without an express social policy orientation—hedge funds, mutual funds, and the like—suggests that they are largely indifferent to the shareholder-proposal process and view such proposals as ineffective tools in driving shareholder returns.

A deeper analysis of each subset of proposal sponsor reveals other significant trends. For example, more than two-thirds of all proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies by individual investors came from Evelyn Davis and members of the Steiner, Chevedden, and Rossi families. These investors, often dubbed “corporate gadflies,”[34] annually sponsor numerous essentially identical shareholder proposals across multiple companies. Their objective seems to be to force changes in corporate management, and their proposals often focus on reinforcing procedural mechanisms that increase shareholder voting power and weaken the discretion of boards of directors. Proposals sponsored by the Steiner, Chevedden, and Rossi families often cover parallel concerns, whereas Ms. Davis typically focuses her proposals on substantially different topics. The subject matter of these corporate gadflies’ proposals will be explored in more detail below.

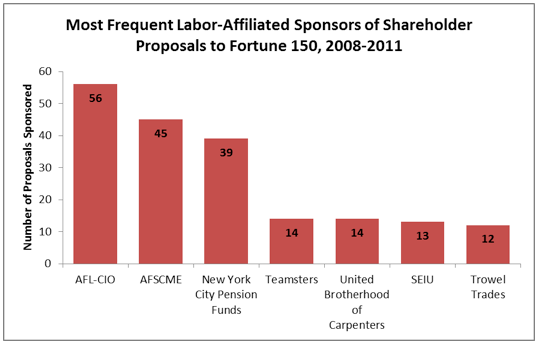

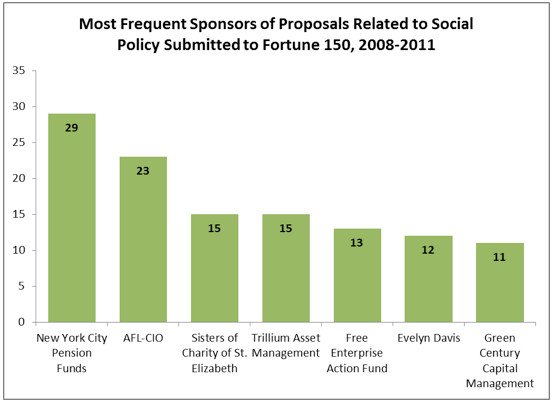

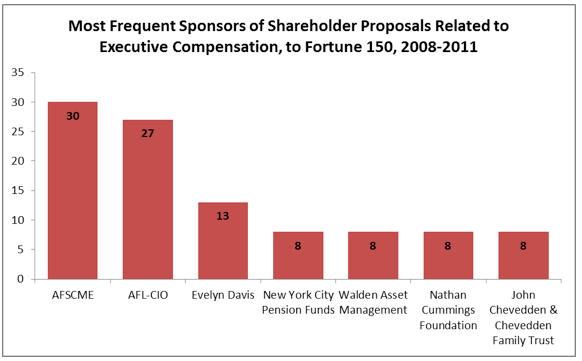

Apart from individual investors, led by the corporate gadflies, labor unions have been the next most active sponsors of shareholder proposals submitted to the Fortune 150 since 2008. Labor unions typically exert their influence through the stock holdings of employee pension funds. A diverse array of labor unions have been active in sponsoring shareholder proposals, led by the large private-sector union American Federal of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) and the large public-sector union American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). The New York City employee pension funds, under the management of the city’s comptroller, have also been very active sponsors of shareholder proposals.

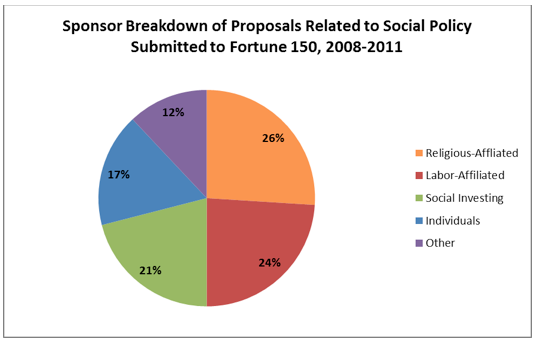

The third major class of shareholder-proposal sponsors encompasses investors who expressly advocate for interests beyond share-price appreciation. Some 45 percent of such proposals emanate from funds with a clear “social policy” orientation. Most of these funds explicitly push “social justice” concerns such as environmental issues or human rights; among these are Trillium Asset Management, Green Century Capital Management, and Walden Asset Management. Such policy funds do not occupy only one end of the ideological spectrum: the Free Enterprise Action Fund, conversely, pushes companies not to engage in social causes, apart from profit maximization.

Another 45 percent of shareholder proposals in this class are sponsored by religious-affiliated investors. Almost 70 percent of these are affiliated with the Catholic church,[35] predominantly religious orders of nuns, led by the most active sponsor of proposals in this class, the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth. Like individual corporate gadflies, groups of nuns are regular attendees of annual corporate meetings.[36]

The remaining 10 percent of shareholder proposals sponsored by socially oriented entities come from nonreligious issue-advocacy organizations not principally organized as investing vehicles. Among such sponsors that regularly introduce shareholder proposals are the National Legal and Policy Center, the Humane Society, and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

b. Where is shareholder activism focused?

The number of shareholder proposals submitted to companies varies according to industry. Manufacturing companies are almost twice as likely to face a shareholder proposal in any given year as are technology companies; other sectors facing a relatively higher number of shareholder proposals include financial services and energy and minerals.

These data suggest that some industries, because they attract more political scrutiny, will collect a higher share of social policy proposals unrelated to executive compensation or corporate governance (for a more detailed discussion of different types of proposal, see section C below). Leading that field are companies in the energy and mineral sector, for which more than two-thirds of all shareholder proposals relate to social policy topics. These companies tend to attract such proposals because they are among the largest corporations, even among the Fortune 150, and because their businesses are often the subject of environmental and geopolitical scrutiny.

After energy and minerals, the sector that attracts the most social policy proposals is technology. These companies also tend to draw scrutiny for their environmental policies, as well as for issues associated with the uses and manufacturing conditions of their technology.

Social policy proposals do not predominate as much in the manufacturing and financial-services sectors. Therefore, these companies attract shareholder proposals for different reasons from those of energy and technology corporations. Manufacturing and financial-services companies are among the largest companies, and the financial crisis has drawn attention to financial companies’ business practices. In addition, the manufacturing sector involves many mature companies and conglomerates, such as General Electric, that may attract special attention—as well as companies related to the automotive sector, which itself underwent an attention-grabbing crisis in 2008.

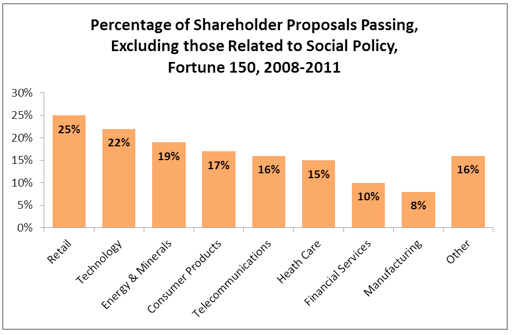

The industrial sectors whose companies receive the largest number of proposals—energy, financial services, and manufacturing—tend to have the smallest percentage of proposals pass. For the energy sector, this phenomenon is partly explained by the number of social policy proposals in its proposal pool (social policy proposals, unlike other kinds, have never been approved by a majority of the shareholders of any Fortune 150 company since 2008). Still, companies in the financial-services and manufacturing sectors remain among those whose proposals are least likely to gain shareholder support even after controlling for the share of social policy proposals submitted. The explanation is likely that many of the additional proposals submitted for these companies are generally not well-regarded among shareholders.

The one sector in which shareholder proposals are most likely to pass is retail. While shareholders at the nation’s largest retailer, Wal-Mart, passed no shareholder proposals—likely because of the company’s sizable family holdings—a “who’s who” of other retailers saw one or more shareholder proposals pass from 2008 through 2011: CVS Caremark, The Home Depot, J. C. Penney, Kohl’s, Kroger, Lowe’s, Macy’s, McDonald’s, Safeway, Staples, Supervalu, TJX, and Walgreens. The types of proposals receiving majority support at retail companies include executive-compensation proposals calling for “say on pay” or restricting “golden parachutes,” as well as corporate-governance proposals calling for majority voting, board declassification, and shareholders’ ability to call special meetings or act by written consent. It is not clear from the data at hand why companies in the retail sector are more likely to see these shareholder proposals pass than those in other sectors. These companies may have had different preexisting norms for corporate governance and executive compensation, they may have had different share-price performance, or they may be owned by different classes of investor.

The data also reveal that labor pension funds and other labor-affiliated investors tend to concentrate their shareholder proposals in particular sectors, which may correlate to union organizing activity. Companies in service-oriented fields (telecommunications, retail, and financial services) are much more likely to receive shareholder proposals sponsored by labor groups than are companies in the manufacturing fields (including general manufacturing as well as energy, health care, and consumer products). Interestingly, the sectors in which labor unions concentrate their shareholder proposals are less likely to be unionized: only 5.6 percent of Americans employed in retail trade and 2.5 percent of those employed in the financial sector are unionized, as compared with 8.8 percent in oil and gas extraction and 11.6 percent in manufacturing.[37] Moreover, unions have made well-publicized recent efforts to organize these lightly unionized sectors.[38] Unions’ particular focus on these sectors therefore may be related more to organizing campaigns than to maximizing share returns.[39]

c. What is the subject of shareholder activism?

The content of shareholder proposals in the ProxyMonitor.org data set has largely aligned across three major categories:

- Substance-based shareholder proposals relating to questions of executive compensation. These types of proposals seek to increase shareholder power over executive-compensation decisions, including overall pay packages, equity compensation, golden parachutes, or “golden coffins” (i.e., insurance-type payouts given to executives’ estates in the event of untimely death).

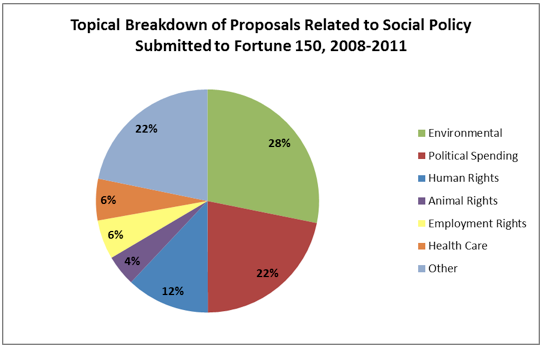

- Substance-based shareholder proposals related to social or policy goals unrelated to traditional agency-cost concerns. These types of proposals have covered such topics as corporate environmental policies; corporate support for health-care reform; human rights, animal rights, and employment rights; and, increasingly, corporate political spending and lobbying.

- Process-based shareholder proposals relating to questions of corporate governance. These types of proposals seek to increase shareholder value by changing the power of shareholders relative to boards, either by modifying voting rules, insisting that all directors are elected annually, enabling shareholders to take action outside the annual meeting process, or separating the positions of chairman and chief executive officer.

Overall, 35 percent of all shareholder proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies from 2008 through 2011 related to process-based corporate-governance, 26 percent related to executive compensation, and 39 percent related to other social or policy goals.

Beyond that overall picture, however, the composition of proposals varied significantly year to year, and such variation explains much of the year-to-year variation in the number of shareholder proposals introduced and their passage rates. As noted previously, the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform mandated that companies themselves regularly submit their executive-pay packages to shareholders for a nonbinding vote. This change doubtless explains, to a large extent, why the number of shareholder proposals relating to executive compensation submitted to Fortune 150 companies fell from 80 in 2010 to 28 for the 134 companies in the data set to have mailed proxy materials by August 1, 2011.

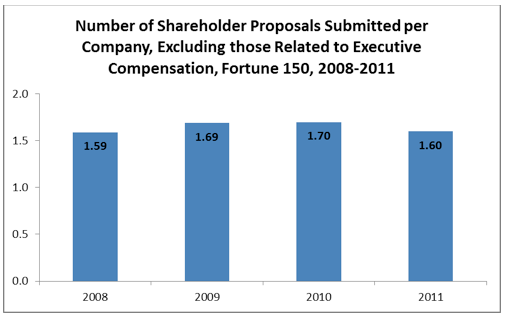

Moreover, the drop-off in proposals related to executive compensation in 2011 is itself sufficient to explain most of the year-on-year variance in the number of shareholder proposals submitted to the Fortune 150. Ignoring proposals related to executive compensation, the number of proposals per company in the data set varied from a low of 1.59 in 2008 to a high of 1.70 in 2010.

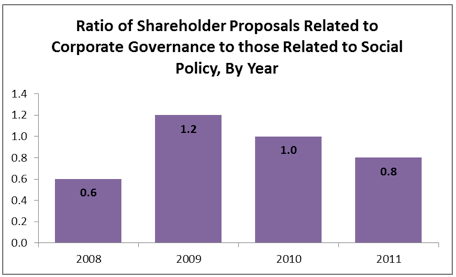

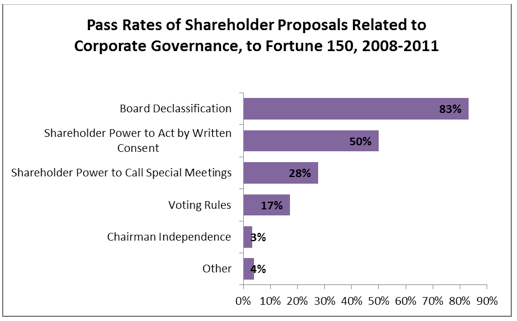

Similarly, shifts in the composition of proposals submitted can explain much of the variation in majority-adoption rates by shareholders across time. Across the entire time period, 21 percent of all shareholder proposals related to process-based corporate-governance changes were embraced by a majority of shareholders, versus only 7 percent of those related to executive compensation. None of the social policy proposals passed during the period studied. The relative number of proposals related to social policy and to corporate-governance questions varied markedly from 2008 to 2011. The ratio of proposals related to corporate governance rather than social policy doubled from 2008 to 2009, before declining somewhat in each of the two following years. The reasons that the number of shareholder proposals varied so much is beyond the scope of this analysis, but likely related to market movement, shareholder voting patterns that influence subsequent proposal efforts, and changes in social and public policy priorities, such as health-care reform and global warming, on the part of sponsoring shareholder activists.

Special Focus: Say on Pay 2011

In recent years, drawing upon British practice, an increasing number of shareholder proposals called for “say on pay” votes, giving shareholders the power to pass advice on senior executives’ compensation packages. Section 951 of Dodd-Frank made such practice mandatory,[40] and in 2011, all public corporations with annual meetings falling after January 21 had to submit their executive-pay packages to shareholders for an advisory vote. In addition, shareholders were permitted to decide whether they wanted to review compensation packages annually, biennially, or triennially.

Shareholders’ response to these two ballot questions revealed somewhat contradictory results: shareholders overwhelmingly preferred to review executive pay annually, but even more overwhelmingly approved of corporate-pay proposals. Although boards of directors variously recommended triennial and biennial pay review, the shareholders of only six companies of the Fortune 150 to have considered the question to date opted for other than annual review: Berkshire Hathaway, Google, Tyson Foods, UPS, Comcast, and Nucor. Notably, and in keeping with trends among a broader subset of companies,[41] these companies have concentrated ownership by founders (e.g., Berkshire Hathaway, Google) or tiered stock-voting structures that empower family founders, employees, or insiders (e.g., Tyson, UPS, and Comcast).

Even as shareholders preferred annual pay review, they overwhelmingly backed executive-pay plans. At only two companies in the Fortune 150—Hewlett Packard and Freeport McMoRan Copper & Gold—did a majority of shareholders disapprove of pay packages, an overall approval rate to date of 98.5 percent, in keeping with broader market trends.[42] Some 53 percent of companies in the Fortune 150 received at least 90 percent shareholder support for their pay plans, and 78 percent received at least 75 percent backing.

The pass rate of pay packages in the ProxyMonitor.org database was close to the rate of passage in broader samples of American companies (e.g., the shareholders at only 1.5 percent of the companies in the ProxyMonitor.org database rejected their boards’ executive-pay proposals, compared with 1.7 percent of companies in the Russell 3000 Index[43] ). However, the large companies in our data set were more likely to face contested votes than the average company overall, as a significantly larger fraction of companies in the Fortune 150 sample passed their compensation plans with less than 75 percent support. This phenomenon is due in no small part to campaigns by organized labor. AFSCME publicly opposed pay packages at five companies—Alcoa, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer—and four of these received under 70 percent shareholder support for their executive-compensation plans.[44] (Alcoa received over 84 percent support, but only after modifying its proposed plan in reaction to labor complaints.)

Overall, though, the first year of mandatory say-on-pay throws into question the rationale for the new rule. Executive pay rose markedly—as much as 23 percent, according to some reports[45]—and was broadly supported by investors. Either such pay packages are not actually destructive of share value, as CEO pay critics claim, or the shareholder-proxy process would seem to be an ineffective means of moderating executive compensation. |

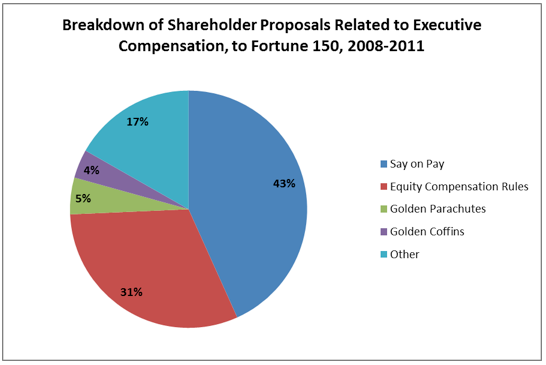

(1) Executive Compensation

Before 2011, shareholder proposals related to executive compensation constituted a sizable percentage of all such proposals. Fully 43 percent of all executive-compensation-related proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies since 2008 have been so-called say-on-pay proposals, calling upon companies to submit executive-compensation packages to shareholders for an advisory vote. As already discussed, these proposals—as well as another common class of proposals, calling for a shareholder vote on golden parachutes (payouts to management in the event of a change in corporate control)—are now required under federal law through the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform (see above: Say on Pay 2011). Other commonly sponsored proposals attempt to limit or place shareholder control over various forms of equity compensation and so-called golden coffins—effectively, insurance-type payouts to the families of prematurely deceased executives.

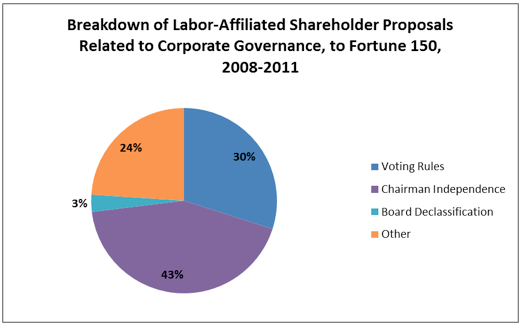

Labor unions have played the dominant role in sponsoring shareholder proposals related to executive compensation, backing 48 percent of all such proposals submitted to Fortune 150 companies since 2008. AFSCME and the AFL-CIO are by far the most frequent sponsors of executive-compensation-related proposals over the period studied. The fact that union pension funds play such an active role in directly challenging management-pay packages could suggest that in these proposals, they seek to gain negotiating leverage over management, rather than merely seeking to maximize share return.

(2) Social Policy

Shareholder proposals related to social policy have covered a variety of topics, including the environment, human rights, animal rights, employment rights, national health-care policy, foreign military sales, and, increasingly, corporations’ political spending and activities. In contrast to other proposals that are, at least theoretically, related to mitigating corporate agency costs, these proposals’ relationship to share value is typically attenuated, at best.

The most common class of social policy proposals relates to environmental issues, typically global warming or general concerns about “sustainability.” The second most common class of proposals revolves around the disclosure of corporate political spending—a class of proposals that has been sponsored with greater frequency over time, no doubt given impetus by the Supreme Court’s controversial 2010 decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,[46] which determined that independent political expenditures by corporations were free speech protected by the First Amendment (see sidebar: Special Focus: Political Spending Proposals).

Social policy proposals, unsurprisingly, are most commonly sponsored by social-investing funds and religious-affiliated groups. They have proposed half of all such proposals. That said, the most frequent individual sponsors of shareholder proposals related to social policy are both labor-affiliated: the New York City pension funds[47] and the AFL-CIO. Fifteen of the 23 such proposals backed by the AFL-CIO related to the political fight over national health-care reform, calling on corporations to adopt “health-care principles.” The New York City pension funds’ concerns included a broad array of topics, including global human rights standards, amending corporate nondiscrimination policy to include sexual and gender-identity discrimination, environmental issues, political contributions and spending, and the MacBride Principles for Equal Employment, Justice, and Peace in Northern Ireland.

No social policy proposal submitted to a Fortune 150 company since 2008 has passed, perhaps because such proposals are far afield from the traditional concerns of corporate law: attempting to mitigate manager-shareholder agency costs.[48]

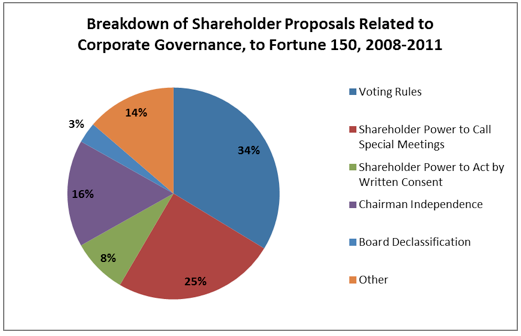

(3) Corporate Governance

Corporate-governance-related proposals seek to improve corporate performance or mitigate agency costs by changing the processes through which boards are governed. A plurality of these proposals submitted to the Fortune 150 since 2008 related to voting rules. Most voting-rule proposals were of one of two types:

- “Majority voting” proposals sought to ensure that directors would only be elected upon receiving a majority of votes—thus enabling shareholder activists to defeat proposed directors’ election, without mounting a proxy contest in which they propose an alternative candidate; at companies without such majority-voting provisions, board-nominated directors are elected as long as they receive a plurality of votes. Some of these majority-voting proposals include, or are limited to, company bylaws.

- “Cumulative-voting” proposals, in contrast, would enable shareholders to aggregate their votes behind a single candidate. For example, in a nine-director board, shareholders could cast all nine of their director votes per share for a single individual. Cumulative voting would enable certain shareholders, such as labor-union-affiliated funds, to pool their votes and elect a minority slate of their own candidates to the board in a contested election—for example, by nominating three candidates and then aggregating all their votes behind those three candidates.[52]

About one-quarter of all proposals related to corporate governance would enable shareholders to call special meetings, outside the annual meeting process. Proponents of greater shareholder influence argue that such mechanisms are important to empowering shareholders year-round, while opponents typically contend that such mechanisms are unnecessary and would permit small groups of shareholders to impose costs on other shareholders to push agendas unrelated to corporate performance.[53] Typically, special-meeting requirements insist on a percentage-ownership threshold before a special meeting would be authorized, and the issue at play in many such proposals is whether a smaller percentage—as low as 10 percent of outstanding shares—should be sufficient to call a meeting.

Special Focus: Political Spending Proposals

In recent years, public corporations have faced a rising number of proposals regarding their political spending, lobbying, or public policy priorities. Such efforts doubtless gained momentum from the Supreme Court’s controversial 2010 decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission,[49] which determined that corporate political expenditures were free speech protected by the First Amendment.

Views on the appropriateness of such proposals tend to depend on views about the scope of shareholder voting rights. Harvard’s Lucian Bebchuk and other leaders of the “shareholder democracy” movement have welcomed the push for greater shareholder input into corporate political speech.[50] Other corporate-law scholars, including Illinois’s Larry Ribstein, have been skeptical that “shareholder voting on corporate speech could amplify activist business skeptics while muting the diversified shareholders who would prefer that business views be heard” and have worried that “[t]he most likely effect (and possible intent) of requiring shareholder voting on corporate contributions would be to burden and therefore reduce corporations’ ability to speak at all.”[51]

Shareholder proposals related to political spending are overwhelmingly backed by labor-affiliated and social-investing funds, each of which tends to support public-policy agendas and candidates at odds with those backed by most of the large corporations in which they hold shares. To date, no shareholder proposal concerning corporate political speech has approached majority support, though several such proposals have garnered backing from at least 30 percent of shareholders, and the submission of such proposals deserves careful attention going forward.

|

A related shareholder proposal would enable shareholders to act outside the annual meeting process not by calling meetings but by written consent. Such proposals first appeared at Fortune 150 in 2010, and the number of proposals seeking shareholder action by written consent nearly doubled in 2011.

About one in six shareholder proposals called for separating the position of chairman and CEO at the corporation. Sponsors of these proposals argue that individuals serving jointly as chairman and CEO face an inherent conflict between their management and shareholder-protection roles. Opponents of these proposals argue that combining the role of chairman and CEO has long been standard practice at some companies and can be more appropriate than separating the positions, depending on a company’s circumstances, including the value added by inside-management knowledge in leading board activities. Essentially, opponents of such proposals assert, there is no one-size-fits-all solution most appropriate for board leadership.[54]

A final significant corporate-governance-related proposal calls on boards to “declassify,” i.e., to eliminate staggered director terms so that each director is subject to annual shareholder election. Supporters of these proposals argue that staggered board terms insulate boards against potentially hostile acquirers and thus exacerbate agency costs to shareholders’ disadvantage. These proposals’ opponents defend board continuity as important to protecting shareholders and are typically defenders of board discretion in considering takeover bids.[55]

Proposals to declassify the board, while a small percentage of corporate-governance proposals, are by far the most likely to receive support from a majority of shareholders. Fully five in six such proposals were approved at Fortune 150 companies from 2008 to 2011. The next most regularly adopted proposals were those calling for shareholder action by written consent, which were supported by a majority of shareholders half the time. More than a quarter of all proposals seeking to expand shareholders’ power to call special meetings were supported by a majority of shareholders. Although only one in six proposals related to voting rules was approved, the total adoption rate of such proposals is skewed by the fact that a majority of such proposals called for cumulative voting, and several others called for the reimbursement of proxy expenses, none of which received majority shareholder support. More than 50 percent of all proposals that called for the majority election of directors received support from a majority of shareholders.

Individual investors sponsored over 70 percent of all proposals related to corporate-governance rules, led by the chief corporate gadflies, Evelyn Davis and members of the Steiner, Chevedden, and Rossi families. Labor unions backed one-quarter of all such proposals, led by AFSCME and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters. Religious groups and socially oriented investors sponsored a mere 2 percent of these proposals.

The interests of individual investors and labor unions appear substantially different, based on the shareholder proposals in this category that they propose, and there is variation among individual corporate gadflies in the types of proposals that they sponsor. The subset of proposals backed by the Steiners and Cheveddens is almost identical, with particular focus placed upon enabling shareholder action outside the annual meeting process, by calling special meetings or through written consent, and on voting rules, predominantly those calling for the majority voting of directors. Evelyn Davis, in contrast, has focused her corporate-governance-related shareholder proposals on voting rules, and her proposals in that area exclusively call for cumulative voting.

Special Focus: Proxy Access

The subset of shareholders who want a greater say over corporate management gained potential traction when Section 971 of Dodd-Frank authorized the SEC to adopt a “proxy access” rule forcing public companies to list shareholder-proposed directors on the companies’ own proxy ballots.[56] Shortly after Dodd-Frank was signed into law, on August 25, 2010, the SEC issued Rule 14a-11, by a divided 3–2 vote,[57] which, as adopted in the final rule making, would have required companies to list on their ballots directors proposed by any shareholder that held at least 3 percent of a company’s stock for a minimum of three years.[58] The proposed rule did not take effect for the 2011 proxy season, being stayed pending a court challenge.

The SEC’s proposed proxy access rule appeared likely to empower activist shareholders with an agenda potentially contrary to most stock owners concerned solely with share value: the low ownership and high holding-period threshold would give substantial clout to labor-affiliated funds (which hold sizable shares for long periods of time), while excluding corporate raiders who might actually be creating share value through a prospective takeover (given that such raiders would not hold shares for three years in a takeover situation). On July 22, 2011, a unanimous panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit rejected the SEC’s proposed rule, holding that the commission had acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” in failing to assess adequately the likely economic effects of the proposed regulation.[59] The court recognized the problems with the SEC’s proposed rule, holding that “the Commission failed to respond to comments arguing that investors with a special interest, such as unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value, can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value, and will likely cause companies to incur costs even when their nominee is unlikely to be elected.”[60] At the time that this report went to press, the SEC had not announced whether it would seek review in the Supreme Court of the D.C. Circuit decision.

Although mandatory proxy access appears off the table for now, shareholders could always submit proposals calling on their boards to list shareholder-nominated directors on proxy ballots. Historically, the SEC has rejected such efforts, but given its recent inclination in favor of proxy access, and the enabling language of Dodd-Frank, there is reason to believe that the commission could give 14a-8 approval to shareholder proposals seeking a vote on the question.

|

Labor unions, in sharp contrast to the individual investors, focus substantially on separating the chairman and CEO positions. Indeed, 59 percent of all such proposals are sponsored by labor-affiliated investors. Because such proposals are, like executive compensation, highly sensitive for corporate leaders, labor’s role in backing this class of proposals raises the prospect that unions are attempting to leverage the shareholder-proposal process to gain negotiating position over management.

Conclusion

The empirical evidence analyzed in this report, drawn from the ProxyMonitor.org database, leads to some fairly striking conclusions about shareholder proposals being introduced at large public companies. Overall, the evidence tends to throw into question the motives of shareholder activists submitting proposals for consideration at corporations’ annual meetings and suggests that such shareholder activism may be more a vehicle for interest-group capture of corporations rather than for mitigating agency costs and improving shareholder returns.

First, a very limited group of investors is introducing the overwhelming majority of shareholder proposals at large public companies. Over two-thirds of the proposals introduced by individual investors come from one of four shareholders and their families. Hedge funds, mutual funds, and other institutional investors without ties to organized labor or express “social” purposes unrelated to shareholder return account for only 2 percent of all shareholder proposals introduced at Fortune 150 companies over the last four annual meeting cycles.

Second, there is significant reason to question whether many of the shareholder proposals being introduced are in the interests of the typical diversified investor. Social-investing and religious-affiliated funds are explicitly pursuing goals other than share-price performance. Most proposals being pushed by these investors, as well as politically linked investors such as the New York City Comptroller’s Office, bear little apparent relationship to shareholder return. Labor-affiliated funds’ shareholder proposals tend to involve executive compensation and the separation of the chairman and CEO positions, topics highly sensitive to upper corporate management. Moreover, union funds have tended to introduce more shareholder proposals at companies in industries targeted by ongoing, public labor-organizing campaigns. The evidence thus raises questions about whether labor funds’ role in the shareholder-proposal process is at least somewhat intended to extract concessions from management for the benefit of current union employees rather than for the broader class of shareholders.

The early returns in 2011 say-on-pay voting also throw into question the effectiveness of shareholders’ playing a broader role in corporate governance. That shareholders approved 98.5 percent of all executive-compensation packages, even as managers’ pay increased markedly year over year, suggests either that shareholders overwhelmingly view executive-pay plans as appropriately aligned with their interests or that shareholder voting is an ineffective mechanism for evaluating pay plans’ relationship to share value.

The push among a small subset of shareholders to force disclosure of various aspects of corporate political spending, lobbying, and trade-association membership has generated even less enthusiasm across the broad class of shareholders than the say-on-pay proposals: not a single such proposal has garnered support from a majority of shareholders, with most falling well below the 50 percent threshold. Nevertheless, the increasing incidence of such proposals warrants careful scrutiny in coming years.

The question analyzed by this report is not whether concerns about climate change or health-care reform are well-founded or whether executive pay is too high, but whether such topics are appropriately regulated by shareholder votes in the corporate-governance process. Many issues being raised through shareholder proposals would seem better suited to political rather than corporate elections, and the evidence to date suggests that shareholders are ill-suited to adding value in regulating executive-pay packages.

Much of today’s shareholder activism may be criticized as both undermining the traditional corporate-law focus on managing agency costs and aligning around equity owners’ common interest in shareholder return, as well as facilitating interest-group capture of corporations in an end run around the legislative process. Future analyses drawn from the ProxyMonitor.org database, with an expanded data set, should shed additional light on these important questions.

ENDNOTES

- See, e.g., Paul Rose, Common Agency and the Public Corporation, 63 Vand. L. Rev. 1355, 1356 (2010) (observing that “general trends have supported increased shareholder power and influence within public companies in recent years”).

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (2002).

- The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010) [hereinafter Dodd-Frank Act].

- Compare Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Case for Increasing Shareholder Power, 118 HARV. L. REV. 833 (2005) (arguing for increased shareholder power over corporate governace) with Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 NW. U. L. REV. 547 (2003) (arguing for a traditional director-centered approach to corporate governance).

- But see, e.g., Yonca Ertimur et al., Board of Directors’ Responsiveness to Shareholders: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals, 16 J. CORP. FIN. 53 (2010); and Joao Dos Santos and Chen Song, "Analysis of the Wealth Effects of Shareholder Proposals",VOL. II (U.S. Chamber of Commerce/Workforce Freedom Initiative), May 2009 available at http://www.workforcefreedom.com/sites/default/files/analysis_wealth_effects_volume2.pdf.

- Securities Act of 1933, Pub. L. No. 73-22, Ch. 38, 48 Stat. 74 (1933) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 77a–77aa (2006 & Supp. II 2009)); Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-291, Ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78a–78oo (2006 & Supp. II 2009)) [hereinafter Exchange Act].

- The seminal article attacking a purported “race to the bottom” in American corporate law, centered in Delaware, was written by a former chairman of the federal Securities and Exchange Commission, William Cary, in the 1974 Yale Law Journal. See William L. Cary, Federalism and Corporate Law: Reflections upon Delaware, 83 YALE L.J. 663, 663, 705 (1974) (calling Delaware “both the sponsor and the victim of a system contributing to the deterioration of corporation standards” and decrying corporate law’s “race for the bottom, with Delaware in the lead”).

- See generally Ralph K. Winter, State Law, Shareholder Protection, and the Theory of the Corporation, 6 J. LEGAL STUD. 251 (1977); Winter, The “Race for the Top” Revisited: A Comment on Eisenberg, 89 COLUM. L. REV. 1526 (1989). See also Roberta Romano, Law as a Product: Some Pieces of the Incorporation Puzzle, 1 J.L. ECON. & ORG. 225 (1985) (finding the “race to the top” hypothesis more supported than the “race to the bottom” hypothesis in empirical testing).

- See Roberta Romano, The Genius of American Corporate Law 1 (1993).

- See generally Larry Neal, The Rise of Financial Capitalism: International Capital Markets in the Age of Reason, 118 (1990) (“The East India companies of the Dutch and of the English represented the most successful examples of merchant organization in the early modern era. . . . [T]he most important institutional innovation made by the two companies [was] the transformation of merchant trading or working capital committed initially to the duration of a particular voyage into fixed or permanent capital committed perpetually to the enterprise. The transformation was effected quickly by the Dutch company, apparently by 1612, whereas the English company had certainly made the transition by 1659. After that transformation, both companies were joint-stock corporations whose shares were actively traded in surprisingly modern stock exchanges in both Amsterdam and London.”).

- In accounting, corporate finance, and bankruptcy law, equity owners have the lowest priority claim to a corporation’s assets; i.e., owners of equity capital are only paid after all other creditors and claimants in a corporate liquidation. Cf. Eugene F. Fama, Agency Problems and the Theory of the Firm, 88 J. Pol. Econ. 288, 288-89 (1980) (arguing against “the typical presumption that a corporation has owners in any meaningful sense” and instead defining equity owners by their entitlement only to a residual claim on the corporation).

- See generally Adolph A. Berle & Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (The MacMillan Company, 1932) (a classical exploration of agency costs in the American corporation which remains a principle focus of corporate-law literature).

- See, e.g., Guth v. Loft, Inc., 5 A.2d 503 (Del. 1939) (“Corporate officers and directors . . . . stand in a fiduciary relation to the corporation and its stockholders.”).

- See, e.g., Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d 858, 872 (Del. 1985) (“Since a director is vested with the responsibility for the management of the affairs of the corporation, he must execute that duty with the recognition that he acts on behalf of others. Such obligation does not tolerate faithlessness or self-dealing.”), overruled in other part by Gantler v. Stephens, 965 A.2d 695, 713 (Del. 2009) (restoring Delaware law to “classic” form “where a fully informed shareholder vote approves director action that does not legally require shareholder approval in order to become legally effective”).

- See Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d at 872 (“[F]ulfillment of the fiduciary function requires more than the mere absence of bad faith or fraud. Representation of the financial interests of others imposes on a director an affirmative duty to protect those interests . . . .”).

- See id. (“The business judgment rule exists to protect and promote the full and free exercise of the managerial power granted to Delaware directors. The rule itself is a presumption that in making a business decision, the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company. Thus, the party attacking a board decision as uninformed must rebut the presumption that its business judgment was an informed one.” (citations and internal quotation marks omitted)).

- See, e.g., DEL. CODE ANN., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (“Unless directors are elected by written consent in lieu of an annual meeting as permitted by this subsection, an annual meeting of stockholders shall be held for the election of directors on a date and at a time designated by or in the manner provided in the bylaws.”).

- In Dodge v. Ford Motor Company, 170 N.W. 668. (Mich. 1919), the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that Henry Ford had a fiduciary duty to manage Ford Motor Company for the benefit of shareholders rather than employees or the broader community. In the academic literature, Adoph Berle and Gardiner Means were early defenders of the primacy of shareholders’ interests in governing corporate managers’ fiduciary duties, see supra note 12, and shareholder primacy was buttressed by later law and economics articles conceiving of the corporate form as a nexus of contracts. See, e.g., Armen A. Alchian & Harold Demsetz, Production, Information Costs, and Economic Organization, 62 AM. ECON. REV. 777 (1972); Michael C. Jensen & William H. Meckling, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure, 3 J. FIN. ECON. 305 (1976).

- See, e.g., Jeffrey N. Gordon, The Rise of Independent Directors in the United States, 1950-2005: Of Shareholder Value and Stock Market Prices, 59 Stan. L. Rev. 1465, 1520-26 (2007) (“The hostile takeover movement of the 1980s brought unprecedented emphasis to shareholder value as the ultimate corporate objective.”). See also John C. Coffee, Jr., Shareholders Versus Managers: The Strain in the Corporate Web, 85 MICH. L. REV. 1, 2-7 (1986).

- See, e.g., Roberta Romano, A Guide to Takeovers: Theory, Evidence, and Regulation, 9 YALE J. ON REG. 119, 120 (1992) (“The empirical evidence is most consistent with value-maximizing, efficiency-based explanations of takeovers.”).

- See Gordon, supra note 19, at 1530 (“The 1990s board undertook . . . . to fashion executive compensation contracts that better aligned managerial and shareholder objectives, to give managers high-powered incentives to maximize shareholder value. In light of other institutional constraints, this meant stock options.” (footnote omitted)).

- See id. at 1533-34 (“[Another] element of the 1990s board’s focus on shareholder value in the market for managerial services was the ‘golden parachute,’ a generous severance package that was another alignment mechanism. . . . In the case of an uninvited premium takeover bid, such packages often converted CEOs from opposition to acquiescence.”).

- See John C. Coffee, What Caused Enron? A Capsule Social and Economic History of the 1990s, 89 CORNELL L. REV. 269, 297 (2004)( “…between 1992 and 1998, the median compensation of Standard and Poor's (S&P) 500 chief executives increased by approximately 150%, with option-based compensation accounting for most of this increase. (footnote omitted) The critical point is that in the 1990s, senior executive compensation shifted from being primarily cash-based to primarily stock-based.”). See also Eric Dash, Stock Options at Wholesale, N.Y. TIMES, Apr. 29, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/29/business/29options.html?pagewanted=print.

- See, e.g., Lucien A. Bebchuk et al., Managerial Power and Rent Extraction in the Design of Executive Compensation, 69 U. CHI. L. REV. 751 (2002) (“Analyzing the large body of empirical evidence on executive compensation, we have concluded that the evidence supports the view that managerial power plays a significant role [in inflating executive salaries].”).

- Reacting to public hostility to the wave of hostile takeovers in the 1980s, many states enacted “constituency” or “stakeholder” statutes that would “allow a board to take non-stockholder/non-monetary considerations into account when contemplating a takeover offer,” including the interests “of corporate employees, customers, creditors, suppliers, and the local communities where the corporations are located.” Mark G. Robilotti, Codetermination, Stakeholder Rights, and Hostile Takeovers: A Reevaluation of the Evidence from Abroad, 38 HARV. INT'L L.J. 536, 536-37 (1997). Largely conceived as borrowing from corporate models in Germany and Japan, stakeholder statutes were defended by some scholars in an American context, see, e.g., Morey W. McDaniel, Stockholders and Stakeholders, 21 STETSON L. REV. 121, 151 (1991) (defending such legislation as consistent with early nineteenth-century norms), while other commentators were more critical, see, e.g., Mark E. Van Der Weide, Against Fiduciary Duties to Corporate Stakeholders, 21 DEL. J. CORP. L. 27, 86 (1996) (“Restricting the scope of managers' fiduciary duties to shareholders alone will increase social wealth.”).

- Parallel to and overlapping with calls for stakeholder capitalism is the push for “corporate social responsibility.” The debate about the social obligations of corporations, if any, is deeply rooted: during the Great Depression, Harvard professor Merrick Dodd called for “a view of the business corporation as an economic institution which has a social service as well as a profit-making function.” E. Merrick Dodd, Jr., For Whom are Corporate Managers Trustees?, 45 HARV. L. REV. 1145, 1148 (1932); Columbia law professor Adolph Berle attacked Dodd’s notion, arguing that if “the fiduciary obligation of the corporate management and ‘control’ to stockholders is weakened or eliminated, the management and ‘control’ become for all practical purposes absolute.” Adolf A. Berle, Jr., For Whom Corporate Managers Are Trustees: A Note, 45 HARV. L. REV. 1365, 1367 (1932). The modern push for “corporate social responsibility” generally traces to a pair of 1970s books, Where the Law Ends, by Christopher Stone (1975), and Taming the Giant Corporation, by Ralph Nader, Mark Green, and Joel Seligman (1976). For a critique of the early concept of corporate social responsibility advocated by these authors, see David L. Engel, An Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility, 32 STAN. L. REV. 1, 1 (1979) (“Any mandatory governance reforms intended to spur more corporate altruism are almost sure to have general institutional costs within the corporate system itself. . . . But the proponents of “more” corporate social responsibility have never bothered to analyze or examine, from any clearly defined starting point, even just the benefits they anticipate from reform . . . .”). Such debates continue on in the present day. See, e.g., Peter Muchilinski, Corporate Social Responsibility and International Law: the Case of Human Rights and Multinational Enterprises, in THE NEW CORPORATE ACCOUNTABILITY 431 (Doreen McBarnet et al. eds., 2007).

- See, e.g., Lucian A. Bebchuk, The Myth of the Shareholder Franchise, 93 VA. L. REV. 675 (2007); and idem, The Case for Increasing Shareholder Power, 118 HARV. L. REV. 833 (2005), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=387940.

- 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007).

- Pursuant to Exchange Act, supra note 6, at §§ 78m, 78n & 78u; 15 U.S.C. §§ 80a-1 to 80a-64 (2000) (pursuant to, Investment Company Act of 1940, Pub. L. No. 76-768, 54 Stat. 841(1940)).

- See Milton V. Freeman, An Estimate of the Practical Consequences of the Stockholder's Proposal Rule, 34 U. DET. L.J. 549, 549 (1957) (characterizing Rule 14a-8 as “merely a recognition of rights granted by state law”). Cf. DEL. CODE ANN., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”).

- See also generally Roberta Romano, Less Is More: Making Shareholder Activism a Valued Mechanism of Corporate Governance, 18 Yale J. Reg. 174, 231-32 (2001) (“It is quite probable that private benefits accrue to some investors from sponsoring at least some shareholder proposals. The disparity in identity of sponsors—the predominance of public and union funds, which, in contrast to private sector funds, are not in competition for investor dollars—is strongly suggestive of their presence.”).

- OIG Department of Labor Report, Proxy-Voting May Not Be Solely for the Economic Benefit of Retirement Plans, Rpt. No. 09-11-001-12-121, intro (March 31, 2011), http://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2011/09-11-001-12-121.pdf. Under the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), fiduciary duties governing employee benefit plan investment portfolios require that “in voting proxies. . . the responsible fiduciary shall consider only those factors that relate to the economic value of the plan's investment and shall not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income to unrelated objectives.” 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008).

- See Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 3, at §951 (2010); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402 (2011).

- “Corporate Gadflies” as commonly used in Charles M. Yablon, Overcompensating: The Corporate Lawyer and Executive Pay, 92 COLUM. L. REV. 1867, 1895 (1992); see also Jessica Holzer, Firms Try New Tack Against Gadflies, WALL ST. J., Jun. 6, 2011,

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304906004576367133865305262.html.

- In the aggregate, Catholic-affiliated entities sponsor more shareholder proposals than any single proponent (though Catholic organizations sponsor fewer than one-third as many proposals as labor-affiliated organizations, in the aggregate).

- See Stephen Gandel, Nuns vs. Bankers: The Shareholder Proxy Wars, TIME MAG., Apr. 21, 2010, http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1981861,00.html (reporting on the shareholder activism of religious orders of nuns in anticipation of the 2010 proxy season).

- See United States Department of Labor, Union Affiliation of Employed Wage and Salary Workers by Occupation and Industry (2010), http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t03.htm.

- See, e.g., Steven Greenhouse, Union Effort Turns Its Focus to Target, N.Y. TIMES, May 23, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/24/business/economy/24target.html?pagewanted=all; Mike Elk, Too Big Not to Organize: SEIU-International Coalition Try to Unionize the Banks, HUFFINGTON POST, July 29, 2010, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mike-elk/too-big-not-to-organize_b_663940.html.

- For union shareholder activism, see, e.g., Stephen M. Bainbridge, Shareholder Activism in the Obama Era, UCLA School of Law, Law-Econ Research Paper No. 09-14 (July 22, 2009), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1437791; and idem, Unions Abusing Pension Funds for Politics, WASH. EXAMINER (Sept. 6, 2007), http://washingtonexaminer.com/node/421936. For a specific discussion of public-union fund activism, see also Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Trial Lawyers, Inc.: California 12-13 (2005), http://www.triallawyersinc.com/ca/ca06.html.

- See Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 3, at §951 (2010); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402 (2011).

- See Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, Updated Say-on-Pay Scorecard: Reprise (July 8, 2011), http://www.davispolk.com/briefing/corporategovernance/blog.aspx?topic=2&All=null&IsListParentTopic=true.

- See Ted Allen, U.S. Proxy Season Review: ‘Say on Pay’ Votes (June 28, 2010), http://blog.issgovernance.com/gov/2011/06/us-proxy-season-review-say-on-pay-votes.html.

- Id.

- See Id.

- See Pradnya Joshi, We Knew They Got Raises. But This?, N.Y. TIMES, JUL. 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/03/business/03pay.html?pagewanted=all.

- Citizens United v. Fed. Election Comm'n, 130 S. Ct. 876 (2010) [hereinafter Citizens United].

- Unlike traditional labor unions, many state- or local-managed pension funds are overseen by boards that mix union representatives. The New York City Employees’ Retirement System, for example, is governed by a board comprised of three union representatives, the city’s comptroller and public advocate, each borough president, and the mayor’s delegate. See NYC Employees’ Retirement Systems, Board of Trustees, http://www.nycers.org/(S(2xvoix55fy2piu45i3e4hm55))/about/Board.aspx (last visited Sept. 1, 2011).

- Rather than mitigating agency costs, these proposals seem to be largely a part of a larger political, social, or litigation strategy. See, Jonathan Drimmer, Think Globally, Sue Locally: Out-of-Court Tactics Employed by Plaintiffs, Their Lawyers, and Their Advocates in Transnational Tort Cases (U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, June 2010), http://www.instituteforlegalreform.com/../images/stories/documents/pdf/international/thinkgloballysuelocally.pdf.

- Citizens United, supra note 46 (2010).

- See Lucian A. Bebchuk & Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Corporate Political Speech: Who Decides?, 124 HARV. L. REV. 83-117 (2010), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1670085.

- See Larry E. Ribstein, The First Amendment and Corporate Governance (Illinois PUB. LAW. Research Paper NO. 10-24, 2011) available at http://truthonthemarket.com/2011/05/24/the-first-amendment-and-corporate-governance-2/, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1739264.

- The utility of cumulative voting would be multiplied were shareholders of a certain segment of a company’s stock able to list their own preferred candidates for director on companies’ own proxy ballots. The possibility that federal rules would permit such proxy access has been a significant battle in recent years (see sidebar: Special Focus: Proxy Access), which may help to explain the incidence of cumulative-voting proposals.

- See, e.g., Citigroup Inc., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposal 11 (March 12, 2010), available at http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/831001/000119312510055351/ddef14a.htm#toc91376_37.htm (Steiner’s statement: “A special meeting allows shareowners to vote on important matters, such as electing new directors, that can arise between annual meetings. If shareowners cannot call a special meeting investor returns may suffer.”) But see management’s statement: “Holding a special meeting of our stockholders would be a costly undertaking, involve substantial planning, and require us to commit significant resources and attention to the legal and logistical elements of such a meeting. Moreover, lowering the percentage to 10% would permit one or a few stockholders who own a smaller percentage of Citi’s common stock to call a special meeting that may serve their narrow purposes rather than those of the majority of our stockholders.”

- See e.g., Citigroup Inc., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the