PROXY MONITOR 2015

FINDING 3

Special Report: Public Pension Funds’ Shareholder-Proposal Activism

Public pension funds sponsored a record number of shareholder proposals in 2015; Large public pension funds’ prior shareholder-proposal activism has not generated share value

By James R. Copland

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive advisory votes at America’s largest companies. This is the 33rd publication in a series of reports by Manhattan Institute Center for Legal Policy director James R. Copland, each drawing upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-proposal process.[2]

|

America’s largest publicly traded companies are facing more shareholder proposals in 2015, driven principally by a “proxy access” campaign led by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer, who oversees the city’s $160 billion pension funds for public employees.[3] Elected in 2013, Stringer has launched a Boardroom Accountability Project seeking, in part, proxy access, which grants shareholders with a certain percentage of a company’s outstanding shares the right to list a certain number of candidates for the company’s board of directors on the company’s proxy statement.[4] As noted in an earlier finding, Comptroller Stringer’s proxy-access campaign has won substantial shareholder support at most companies where his proposal was introduced.

Although it is too soon to assess the impact of Comptroller Stringer’s push for proxy access, we can evaluate shareholder-proposal activism by state and municipal public employee pension funds in previous years. From 2006 to the present, state and municipal pension funds have sponsored 300 shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies. More than two-thirds of these were introduced by the pension funds for the public employees of New York City and State.

This special report examines the shareholder-proposal activism of the New York City and State funds as well as that of comparable large public-employee pension funds in California and Florida—each of which have also been involved in shareholder-proposal activism over the aforementioned period, albeit much more modestly, and which collectively with the New York funds comprise the five largest U.S. state and municipal public pension plans by assets.

Section I examines such funds’ shareholder-proposal activism, over time and by subject matter, as well as voting results. Section II looks at how their shareholder-proposal activism may have impacted subsequent share value in targeted companies. The study concludes that these publicly traded pension funds’ shareholder-proposal activism did not tend to create share value; and that the New York State fund’s activism—which traces to 2010 under current comptroller Thomas DiNapoli—has been negatively associated with subsequent share-price movement relative to the broader stock market.

I. Shareholder-Proposal Activism by Public-Employee Pension Funds

Pension plans for public employees are among the largest investors in the marketplace. Among the 200 largest defined-benefit pension plans[5] in the United States, two-thirds of total assets ($3.2 trillion of $4.8 trillion) are held by plans for public employees.[6] The largest public-employee fund, the Federal Retirement Thrift Savings Plan, serves federal-government employees,[7] and has not been involved in shareholder-proposal activism. The next five largest public-employee pension plans are:

- California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), with $297 billion in assets

- California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) ($187 billion)

- New York State Common Retirement Fund ($178 billion)

- New York City Retirement Systems ($159 billion)

- Florida State Board of Administration ($155 billion)[8]

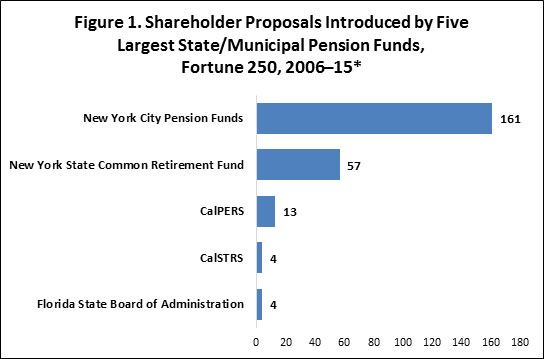

These funds can differ in investment strategy and approaches to shareholder activism,[9] as well as in commitment to “social investing” principles. As shown in Figure 1, the degree to which such funds have been involved in shareholder-proposal activism also varies markedly. Just as the shareholder-proposal process itself is dominated by a small subset of investors[10]—including almost no institutional investors without an affiliation with public officials, organized labor, or a “social investing” purpose or religious/policy orientation—most public-employee pension funds file no shareholder proposals. In addition to the state employees’ funds for California, New York, and Florida, six other state employee funds filed at least one shareholder proposal at a Fortune 250 company in the last ten years, introducing between one and nine proposals each over the decade.[11] Apart from the New York City funds, the only municipal funds to sponsor shareholder proposals have been the Philadelphia Public Employee Retirement System (14 proposals) and the firefighters’ pensions for Kansas City (15 proposals) and Miami (six proposals).

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

Trends over Time

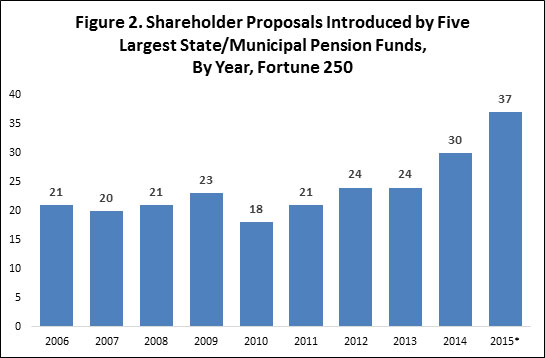

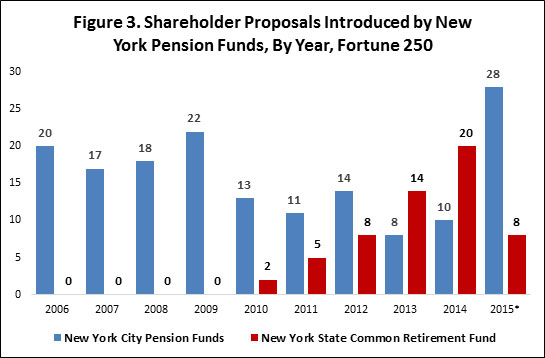

These public-employee pension funds have sponsored shareholder proposals throughout the past decade, though their activity has notably increased during the last two proxy seasons (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 3, this uptick is substantially attributable to a significant increase in shareholder-proposal activism by the New York State Common Retirement Fund, which sponsored no shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies during 2006–09 but then increased the number of proposals it introduced each year through 2014, when it sponsored 20 proposals, before reducing its activity in 2015, sponsoring only eight proposals to date.

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

The other cause of increased shareholder-proposal activism among public-employee pension funds is Comptroller Stringer’s proxy-access push for the New York City funds. During 2006–09, under then-comptroller William Thompson, the New York City funds sponsored 18–22 shareholder proposals annually at Fortune 250 companies. That number fell to 8–14 under Thompson’s successor, John Liu—a trend which continued last year after Stringer’s election in fall 2013. In 2015, Stringer’s first full proxy season since assuming office, the New York City funds sponsored 28 shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies, a record high for an institutional investor dating to 2006. Of the 28 proposals, 22 sought access (among 75 such proposals advanced at companies across the broader stock market).[12]

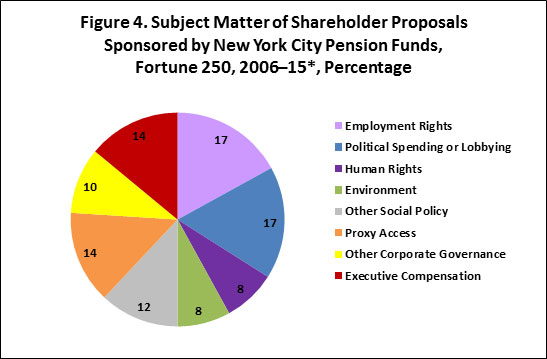

Proposal Subject Matter

Just as public employee pension funds vary in their propensity to introduce shareholder proposals, they vary in the types of proposals introduced. Although most of the 2015 New York City pension funds’ shareholder proposals involve proxy access, a corporate-governance concern, most of the City funds’ proposals historically have involved social or policy issues. As shown in Figure 4, 62 percent of the New York City funds’ shareholder activism over the last decade has involved social or policy concerns with an attenuated, if any, relationship to share value—a number deflated by this season’s proxy-access push. (While 14 percent of the shareholder proposals that New York City funds have introduced over the decade involve proxy access, 22 of the 23 proxy access proposals were filed in 2015.)

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

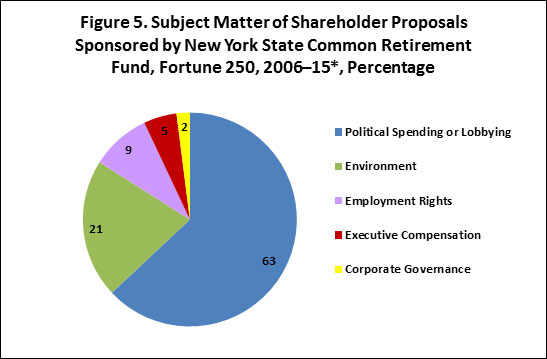

Shareholder proposals sponsored most often by the New York City pension funds involve employment rights (including companies’ sexual orientation and gender identity nondiscrimination policies, their disclosure of race and sex employee data, and their adherence to the Mac Bride Principles for nondiscrimination in Northern Ireland[13]) and the company’s disclosure of various expenditures related to political spending or lobbying. Social or policy issues have been even more dominant in the New York State fund’s shareholder activism—constituting 93 percent of all shareholder proposals sponsored over the period (Figure 5). 63 percent of the New York State fund’s shareholder proposals have involved the company’s political spending or lobbying.

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

In contrast to the New York City and State funds, CalPERS has been far less active in filing shareholder proposals: over the last decade, it has filed only 13 shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies. Eleven of these involved corporate-governance issues—most frequently voting rules—and two involved executive compensation. CalPERS sponsored no shareholder proposals with the largest companies in either 2013 or 2014, before sponsoring one proxy access proposal this year—and lending solicitation support to New York City’s efforts.[14]

CalSTRS and the Florida State Board of Administration were even less active in filing shareholder proposals, each sponsoring only four over the past decade. They also varied in approach. The Florida board’s four proposals each called for “declassifying” the board of directors—i.e., electing all directors annually instead of in staggered terms, thought by advocates to increase share value by making it harder for boards to resist takeovers.[15] The Florida board’s efforts were part of a coordinated campaign on this issue spearheaded by Harvard law professor Lucian Bebchuk, in concert with several multiple state and municipal pension funds,[16] including some of the smaller ones in the ProxyMonitor.org database that sponsored shareholder proposals. In contrast, CalSTRS, like the New York funds, focused its limited shareholder-proposal activism on social issues: three of its four shareholder proposals involved environmental concerns, in addition to a proposal seeking to empower shareholders to call special meetings.

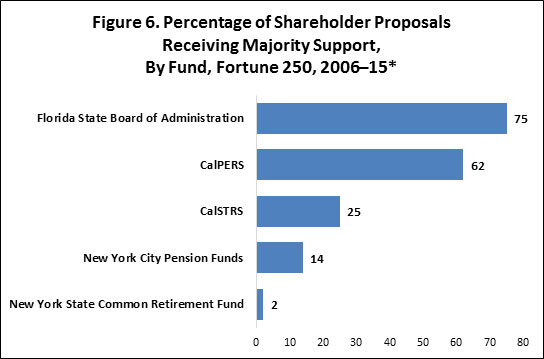

Voting Results

Given the disparate shareholder-investment strategies pursued by public pension funds, such funds’ ability to persuade a majority of fellow shareholders to support their proposals has also varied markedly (Figure 6). Three of the Florida board’s four board-declassification shareholder proposals received majority support, consistent with broad trends for such proposals at large companies.[17] Similarly, more than 60 percent of CalPERS’s proposals, focused on voting rules and other corporate-governance issues, won majority shareholder backing. At the other end of the spectrum, only one of the 57 shareholder proposals sponsored by the New York State Common Retirement Fund received majority support—a 2015 proposal at Staples seeking to limit the potential pay boards could offer executives in severance agreements. 23 of the 161 proposals sponsored by the New York City pension funds received majority support; 18 sought proxy access for director nominees (with 17 in 2015).

*For 2015, 216 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by June 10.

Source: Proxy Monitor

II. Stock Price Reactions to Public Pension Fund Shareholder-Proposal Activism

Pension funds that file shareholder proposals argue that they are an important corporate-governance mechanism for enhancing share value, given that these funds are large diversified investors that tend to “buy and hold” the shares of most large companies in the market, rather than actively entering and exiting positions.[18] Although this rationale most closely follows for corporate-governance proposals that affect director elections—including voting rules, director board terms, and proxy access—funds assert that their “social issue” shareholder activism also comports with share value.[19] (Consistent with this claim, the New York City pension funds expressly identified “climate change” and “board diversity,” in addition to executive compensation, as criteria used to determine which companies to target with shareholder proposals seeking proxy access.)[20]

Critics of pension funds’ shareholder activism worry that “unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value, can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value”[21]—a concern articulated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in 2011, when it threw out the Securities and Exchange Commission’s promulgated mandatory proxy access rule (one substantially similar to that currently being advanced by the New York City funds’ initiative). Perhaps owing to these concerns, the two largest mutual fund groups, Fidelity and Vanguard, have largely opposed the New York City funds’ proxy access proposals.[22]

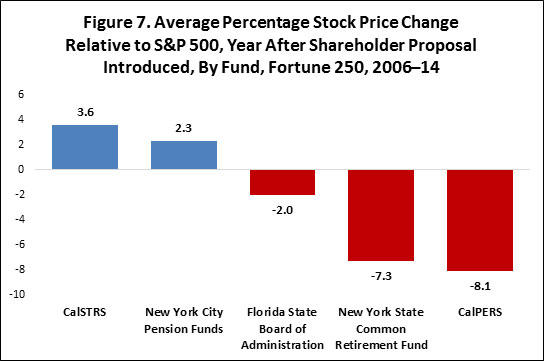

Indeed, the evidence does not support the public pension funds’ claims that their shareholder-proposal activism enhances share value: the Fortune 250 companies targeted by shareholder proposals sponsored by the five largest state and municipal pension funds saw their share price, in the subsequent year, underperform the broader S&P 500 index (by 0.9 percent),[23] with broad variations.

Given such broad variations—and the disparate strategies for shareholder-proposal activism adopted by different public pension funds—I disaggregated these results by fund. As shown in Figure 7, the negative overall results for these public pension funds’ shareholder activism is driven principally by the New York State Common Retirement Fund (7.3 percent below-market returns) and, to a lesser extent, by CalPERS (8.1 percent below, on substantially fewer observations). This result seems curious, given that the former focused its shareholder-proposal activism on never-passing proposals related to corporate political spending and other social issues, while the latter focused its activism on corporate-governance concerns, chiefly voting rules for directors. Through 2014, the companies targeted by the New York City funds’ proposals actually saw their shares outperform, by 2.3 percent, the broader market in the year after the proposal was introduced. (The CalSTRS and Florida board funds saw directionally opposite results, though in a small sample size, with only four proposals each in the dataset.)

Source: Proxy Monitor

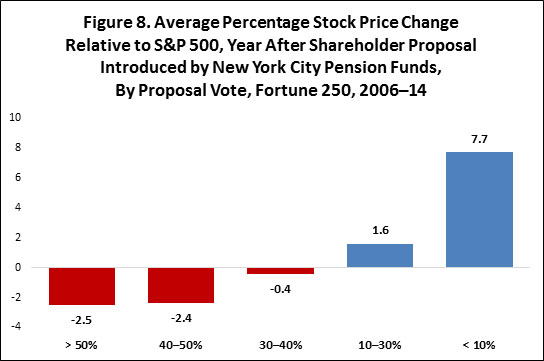

To examine whether the New York City funds’ shareholder proposals might be responsible for the targeted companies’ share-price gains, I segmented the proposals by shareholder support. Rather than supporting this hypothesis, the results strongly undercut it: as shown in Figure 8, the subsequent share-price performance of the companies targeted by New York City pension proposals, relative to broader market trends, is inversely correlated to shareholder support for those proposals. In cases in which the City funds’ proposal received 40 percent or more of the vote, the company’s shares underperformed the market by 2–3 percent, on average, the following year.

Source: Proxy Monitor

The positive overall returns in the New York City funds’ sample is driven heavily by the proposals that received the support of less than 10 percent of shareholders (outperforming the market by 7.7 percent). In essence, to believe that the funds’ shareholder proposals were responsible for that gain, one has to believe that Google’s sensational 83-percent annual stock price increase after its 2009 annual meeting was attributable to the New York City funds’ proposal concerning Internet censorship that had been rejected by 99 percent of shareholders (after being rejected by similarly sweeping margins the two prior years); and that Las Vegas Sands’ 82-percent single-year gain after its 2010 record date, as it continued to reemerge from its financial-crisis stock-price hammering,[24] was due to a proposal calling on the board to promulgate a “sustainability report” that was rejected by 90 percent of shareholders, even after the company returned a staggering 365 percent in the previous year.

If counterintuitive, the notion that shareholder proposals might be more injurious to share value when they receive more shareholder support is not illogical. Since shareholder proposals related to social or policy issues are overwhelmingly rejected by a majority of shareholders,[25] boards and managers should be expected to ignore them in most cases—at least when implementing the proposal was deleterious to share value. For shareholder proposals that garner broader support, however, boards must expend scarce time and resources communicating to investors. Moreover, boards ignore these more-popular proposals at their peril—risking potentially hostile proxy advisors and shareholders, “vote no” campaigns for directors, and the like.[26] Thus, even when a board has determined that the proposal is not in the shareholders’ interest—as is necessarily the case ex ante for any shareholder proposal the board recommends against—the board may capitulate to shareholders’ demands. Because shareholder activists’ leverage over boards and management is positively related to boards’ and managements’ sensitivity to a given proposal, shareholders that have motives unrelated to share value (as hypothesized by the D.C. Circuit) may be able to exploit such sensitivity to pressure management to take actions detrimental to share value. These pressures to act may be particularly heightened not only when shareholder proposals are likely to gain more shareholder support but also when proposals involve executive compensation or corporate leadership structure—essentially the terms by which managers are paid and how and to whom they report.[27]

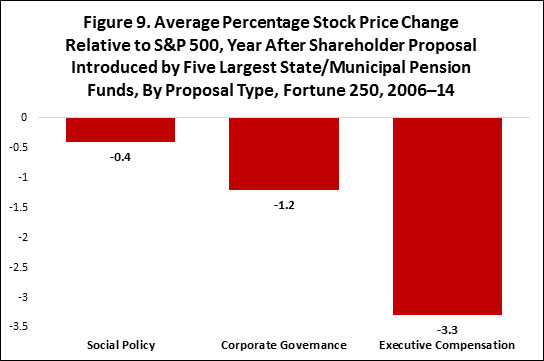

The results shown in Figure 9 conform to this hypothesis. Share-price movements in the wake of social-policy-related shareholder proposals introduced by public pension funds are only modestly negative; for corporate-governance-related proposals, more so; and for executive-compensation-related proposals, more so yet.

Source: Proxy Monitor

Conclusion

The observed negative relationship between public pension funds’ shareholder proposals and subsequent share-price movements for targeted companies may be a result of public pension activists’ pursuit of what the D.C. Circuit called “self-interested objectives” (including interests in pro-labor goals and political ends), or it may follow from a flawed strategy on the part of the funds. It may also be due to random noise—as the positive returns witnessed after the New York City pensions’ least-supported shareholder proposals would suggest. A more robust study would need to control for various factors explaining market valuations. To study this question, the Manhattan Institute Center for Legal Policy and its Proxy Monitor team have commissioned a forthcoming study using a more complex econometric methodology, the results of which largely confirm these initial findings.

These findings substantially undercut the hypothesis that public pension funds’ shareholder-proposal activism adds to share value for the average diversified investor—and suggest such efforts may actually destroy value. Unlike private pension plans, public pension funds are exempt from the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA)[28] and bound only by state-law obligations. Yet these funds collectively hold trillions of dollars in assets, providing for trillions of dollars of pension obligations for workers and retirees, with trillions of dollars of potential taxpayer liabilities: state policymakers should therefore consider adopting appropriate guidelines to mitigate risks.

ENDNOTES

- Under the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders’ discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, § 951 (2010).

- See Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings, http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx (last visited Jun. 19, 2015).

- The elected New York City comptroller manages the City’s pension funds, which serve to provide retirement benefits for the City’s public employees. See Office of the State Comptroller, Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller, http://www.osc.state.ny.us/pension/fiduciary.htm (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). Full fiduciary authority over the funds rests with various boards composed of political and union delegates. For example, the board of the $46 billion Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) includes the comptroller, two mayoral delegates, a delegate from the education chancellor, and three teacher delegates. See TRSNYC, Our Retirement Board, https://www.trsnyc.org/trsweb/aboutUs/ourRetirementBoard.html (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). The board of the $43 billion New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) includes the comptroller, the public advocate, a mayoral representative, each of the five New York City borough presidents, and three union delegates. See NYCERS, Board of Trustees, http://www.nycers.org/(S(azvv04mpy1qd2j5515dyny55))/about/Board.aspx (last visited Sept. 9, 2014).

- See New York City Comptroller, Boardroom Accountability Project, http://comptroller.nyc.gov/boardroom-accountability/ (last visited Apr. 14, 2015) [hereinafter “Boardroom Accountability Project”]; see also Press Release, Comptroller Stringer, NYC Pensions Funds Launch National Campaign To Give Shareowners A True Voice In How Corporate Boards Are Elected: New York City Pension Funds File 75 Proxy Access Shareowner Proposals to Kick Off the Boardroom Accountability Project, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/comptroller-stringer-nyc-pension-funds-launch-national- campaign-to-give-shareowners-a-true-voice-in-how-corporate-boards-are-elected/ [hereinafter “Stringer Press Release”].

- Defined-benefit pension plans have a fixed payment at retirement, paid by a guarantor, typically one’s employer. See Internal Revenue Service, Choosing a Retirement Plan: Defined Benefit Plans, http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/Choosing-a-Retirement-Plan:-Defined-Benefit-Plan. In contrast, defined-contribution plans, such as those under section 401(k) of the Internal Revenue Code, are portable retirement plans with variable outlays, and investments under the control of the retiree.

- Rob Kozlowski, Retirement Plan Assets Rise 8.5%, Pass $9 Trillion, PENSIONS & INVESTMENTS (Feb.9 2015), http://www.pionline.com/article/20150209/PRINT/302099984/retirement-plan-assets-rise-85-pass-9-trillion.

- The Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) is a tax-deferred retirement savings and investment plan that offers Federal employees the same type of savings and tax benefits that many private corporations offer their employees under 401(k) plans. By participating in the TSP, Federal employees have the opportunity to save part of their income for retirement, receive matching agency contributions, and reduce their current taxes. See Thrift Savings Plan, https://www.tsp.gov/index.shtml.

- See Kozlowski, supra note 6.

- For example, the two large California public-employee pension funds, CalPERS and CalSTRS, differ dramatically on how the respond to activist hedge funds’ efforts to influence corporate management, as witnessed by their being on opposite sides of Trian Fund Management’s effort to break up DuPont. See Liz Hoffman & Timothy W. Martin, Largest U.S. Pensions Divided on Activism, WALL ST. J., May 19, 2015, available at http://www.wsj.com/articles/largest-u-s-pensions-divided-on-activism-1432075445.

- See James R. Copland, Proxy Monitor Finding 1: 2015 Proxy Season Early Report (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Spring 2015), http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/2015Finding1.aspx (observing that “in each of the last 10 years, most shareholder proposals . . . have been introduced by a small class of shareholders”).

- States whose funds were involved in at least some shareholder-proposal activism since 2006 are Connecticut, Indiana, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and North Carolina.

- See Stringer Press Release, supra note 4.

- “The MacBride Principles — consisting of nine fair employment principles — are a corporate code of conduct for U.S. Companies doing business in Northern Ireland and have become the Congressional standard for all U.S. aid to, or economic dealings with, Northern Ireland.” Irish National Caucus, MacBride Principles, http://www.irishnationalcaucus.org/principle/the-macbride-principles-the-essence/.

- As discussed in Finding 2, to support the New York City pension funds’ 2015 proxy access proposals, CalPERS has regularly “filed an SEC Form PX14A6G, permitting oral and written communication in support of the proposal, exempt from proxy solicitation rules as long as the investor does not collect actual voting proxies.” James R. Copland, Proxy Monitor Finding 2: 2015 Mid-Season Report (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Spring 2015), http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/2015Finding2.aspx. See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-6(g) (2007) (requiring investors engaging in exempt solicitations to file materials with the SEC).

- See, e.g., Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alma Cohen & Charles C.Y. Wang, Staggered Boards and the Wealth of Shareholders: Evidence from Two Natural Experiments (Nat'l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 17127, June 2011), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w17127. But see, e.g., Martijn Cremers, Lubomir P. Litov, and Simone M. Sepe, Staggered Boards and Firm Value, Revisited, Social Science Research Network, Dec. 19, 2013, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2364165.

- See Shareholder Rights Project, Investors Working with the SRP Clinic, http://srp.law.harvard.edu/clients.shtml.

- See James R. Copland & Margaret M. O’Keefe, Proxy Monitor Report Fall 2013: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Fall 2013) (observing that six of seven proposals seeking board declassification that year received majority shareholder support).

- See Boardroom Accountability Project, supra note 4 (citing objective “to ensure that companies are truly managed for the long-term” and contrasting “short-term investors” that allegedly may “manipulate corporate governance at the expense of those seeking long-term value”).

- See id. (listing “climate change” and “board diversity” among the criteria used for determining which companies to target with proxy access proposals).

- See Stringer Press Release, supra note 4.

- Business Roundtable & Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. SEC, 647 F.3d 1144, 1152 (D.C. Cir. 2011).

- See Gretchen Morgenson, Mutual Fund Giants Vote to Keep the Insiders In, N.Y. Times, May 31, 2015, at BU1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/business/fund-giants-resist-proxy-access-board-shake-ups.html.

- Sample size was 193 proposals, which includes all shareholder proposals available in the Proxy Monitor database from the five largest public-employee pension funds, excluding 2015 proposals and 2014 proposals with a record date after May 2014, and excluding any company that underwent a significant change of control within one year of the record date for the proposal at issue. Share prices were adjusted for stock splits.

- Liz Benston, Las Vegas Sands: A Big Rise, A Big Fall (Jan. 18, 2009), http://lasvegassun.com/news/2009/jan/18/las-vegas-sands-big-rise-big-fall/.

- James R. Copland, Getting the Politics Out Of Proxy Season, WALL ST. J., Apr. 23, 2015, available at http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/miarticle.htm?id=11468 (observing that among Fortune 250 companies, “[n]ot one of the 1,150 shareholder proposals concerning social or policy issues since 2006 got the support of a majority of voting shareholders over board opposition”).

- See ISS, 2015 U.S. Proxy Voting Summary Guidelines 14 (Mar. 4, 2015) (observing that ISS will recommend, on a case-by-case basis, withholding support for directors who do not respond to shareholder proposals receiving the support of a majority of sharheolders), http://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/1_2015-us-summary-voting-guidelines-updated.pdf.

- “Proposals to split the roles of chairman and CEO are particularly sensitive for boards and management because, to implement the proposal, the board would, in effect, have to demote the company’s boss (giving him a formal overseer as chairman) or wrest away his day-to-day management of the corporation. A majority vote in favor of such a proposal is thus often viewed as, in essence, a vote of no confidence in corporate management. The high stakes involved in such proposals may partly explain their particular appeal to investors affiliated with organized labor . . . .” James R. Copland, Proxy Monitor Finding 1, Watching the 2013 Proxy Season (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Spring 2013), http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/2013Finding1.aspx.

- Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), fiduciary duties governing employee benefit plan investment portfolios require that “in voting proxies. . . the responsible fiduciary shall consider only those factors that relate to the economic value of the plan’s investment and shall not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income to unrelated objectives.” 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008). State and municipal public employee plans are exempt from this requirement. See 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).