PROXY MONITOR

REPORT

Fall 2017

Proxy Monitor 2017: Season Review

By James R. Copland and

Margaret M. O’Keefe

Mr. Copland is a senior fellow as well as the director of legal policy at the Manhattan Institute.

Ms. O’Keefe is the Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor project manager.

About the Authors

JAMES R. COPLAND is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, where he has served as director of legal policy since 2003. He develops and communicates novel, sound ideas on how to improve America’s civil- and criminal-justice systems. He has authored many policy reports, book chapters, articles in academic journals including the Harvard Business Law Review and Yale Journal on Regulation, and opinion pieces in publications including the Wall Street Journal, National Law Journal, and USA Today. Copland has testified before Congress as well as state and municipal legislatures. He speaks regularly on civil- and criminal-justice issues and has made hundreds of media appearances in such outlets as PBS, Fox News, MSNBC, CNBC, Fox Business, Bloomberg, C-SPAN, and NPR. Copland is frequently cited in news articles in periodicals including the New York Times, Washington Post, The Economist, and Forbes. In 2011 and 2012, he was named to the National Association of Corporate Directors “Directorship 100” list, which designates the individuals most influential over U.S. corporate governance.

Prior to joining the Manhattan Institute, Copland served as a management consultant with McKinsey & Company in New York and as a law clerk for Ralph K. Winter on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He has been a director of two privately held manufacturing companies since 1997 and has served on many government and nonprofit boards. Copland holds a J.D. and an M.B.A. from Yale, where he was an Olin Fellow in Law and Economics; an M.Sc. in politics of the world economy from the London School of Economics and Political Science; and a B.A. in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was a Morehead Scholar and recipient of the Honors Prize in Economics.

MARGARET M. O’KEEFE is the project manager for the Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor. Her previous employment includes executive-compensation and corporate-governance consulting at Pearl Meyer & Partners. Earlier, O’Keefe worked for more than ten years on proxy advisory consulting, both at the Proxy Advisory Group and at Morrow & Co. She began her legal career at the Chase Manhattan Bank, where she was an associate counsel. O’Keefe is a graduate of St. John’s University School of Law and received an LL.M. in financial-services law from New York Law School.

About Proxy Monitor

The Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive-compensation advisory votes[1] at America’s largest companies. Findings and reports, principally authored by Manhattan Institute Center for Legal Policy director James R. Copland, each draw upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-voting process[2].

|

Data

The ProxyMonitor.org database includes the 250 largest publicly traded American companies, by revenues, as determined by Fortune magazine. Although we loosely refer to this list as the “Fortune 250,” several of the actual Fortune 250 companies are not publicly traded and thus not subject to the proxy rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This means that some of the companies in the Proxy Monitor database are drawn from the broader Fortune 300 group.

Because the Fortune list changes annually, some companies in the Proxy Monitor database, while among the 250 largest companies in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, or 2015, fell out of the list in 2016, the baseline year for the 2017 proxy season.[3] (Other companies listed in the Proxy Monitor database for previous years no longer existed as independent U.S.-based publicly traded companies, due to going private, change of control, or relocation.)[4] Data for 2017 are current to Aug. 31, at which time 226 companies in the 2016 Fortune 250 had held their annual meetings.

Because the Proxy Monitor database is limited to the largest companies by revenues, the analysis in this report does not capture the full set of shareholder-proposal activism, although shareholder proposals tend to be significantly more common at the largest companies. Some commentators have objected to Proxy Monitor data as underinclusive,[5] but the companies in the Proxy Monitor database encompass the majority of holdings for most diversified investors in the equity markets, making this analysis appropriate for the average shareholder. Even among the large companies constituting the Proxy Monitor database, there are significant variations in market capitalization; the five largest companies in the Fortune 250 have a combined market capitalization almost 18 times as large as companies 246 through 250 on Fortune’s list. Thus, from the average shareholder’s perspective, the Proxy Monitor database paints a significantly more accurate picture than do the vote tallies of most shareholder activists, who simply average votes across a much larger data set of companies, without regard to market capitalization.

|

Abstract

Activists, including those motivated principally by social or political agendas, have long used the shareholder-proposal process at the meetings of publicly traded corporations. Under rules promulgated by the Securities and Exchange Commission, such companies must include shareholder proposals on their proxy ballots for consideration by all shareholders if the proposals conform to certain procedural and substantive requirements.

In 2017, several mutual fund companies—among them BlackRock and State Street, the world’s largest and third-largest institutional investors—announced partial agreement with such social activists regarding at least the issues of gender diversity on boards and climate change. For the first time in the 12 years covered by the Proxy Monitor database, two climate-change-related shareholder proposals received majority shareholder support at a Fortune 250 company over board opposition, at ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum.

This report reviews the 2017 proxy season to shed light on these trends. It finds:

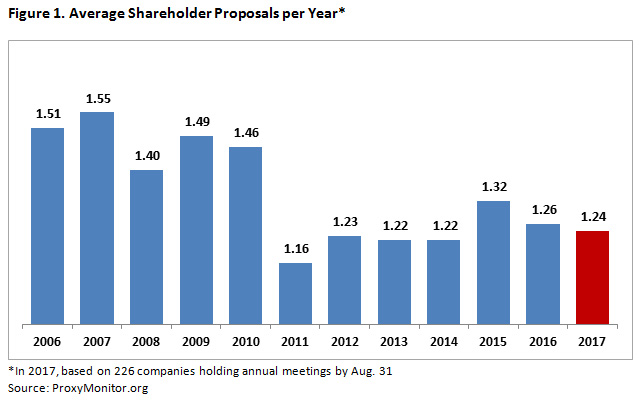

- The average company faced 1.24 shareholder proposals on its proxy ballot, down from 1.26 last year and 1.32 in 2015.

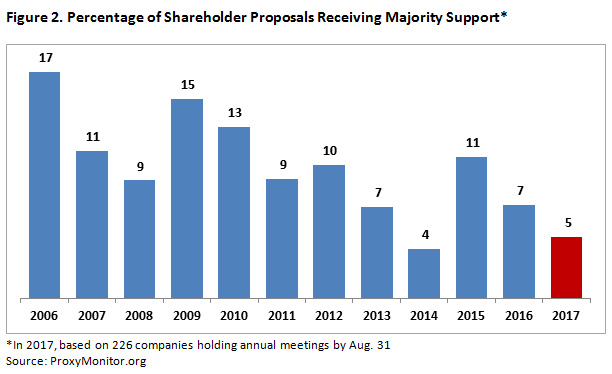

- Only 5% of shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders—down from 7% last year and 11% in 2015.

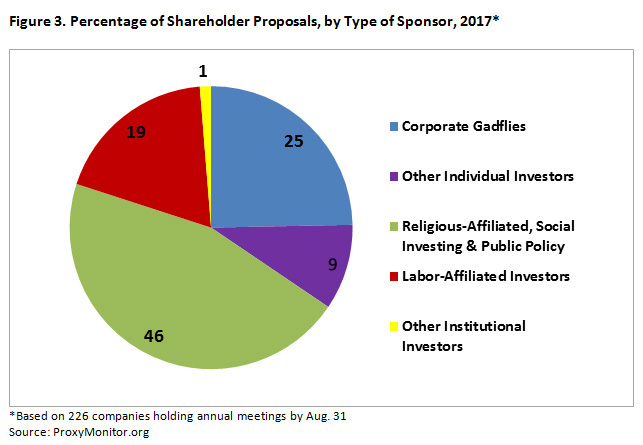

- A limited group of shareholders has submitted the overwhelming majority of shareholder proposals. Just three individuals and their family members sponsored 25% of all proposals.

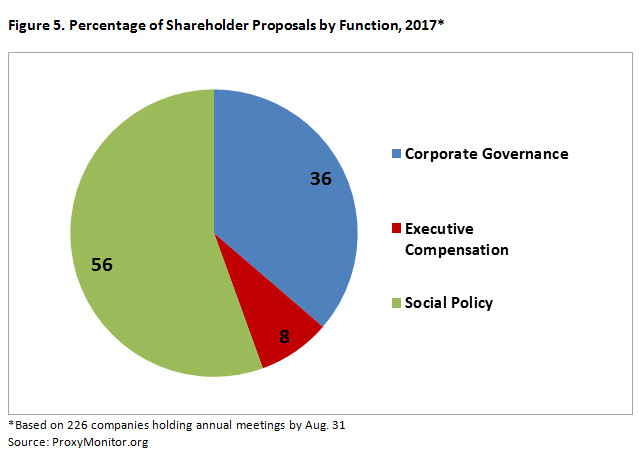

- Proposals related to social or policy concerns with a limited relationship to share value constituted 56% of all shareholder proposals in 2017.

Introduction

The 2017 proxy season was a watershed for social activists seeking to change the operations of large American businesses. On March 7, State Street Global Advisers, the world’s third-largest institutional investor,[6] launched a campaign to pressure companies to add more women to their boards—symbolically installing a bronze statue, “Fearless Girl,” facing the iconic “Charging Bull” that has graced Wall Street since 1989.[7] On March 13, BlackRock, the world’s largest mutual fund company,[8] announced that it, too, would prioritize talking with companies on “gender balance on boards,” as well as “climate risk.”[9]

During the proxy season, substantively identical environment-related shareholder proposals at ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum each received the support of a majority of shareholders. These proposals each asked the respective company to “publish an annual assessment of the long-term portfolio impacts of technological advances and global climate change policies.” These were the first two environment-related shareholder proposals to win majority shareholder support in the 12-year history tracked in the Proxy Monitor database.

The shareholder-proposal process has long enabled activists to put their pet issues on the agendas at the meetings of publicly traded corporations. Under rules promulgated by the Securities and Exchange Commission, such companies must include shareholder proposals on their proxy ballots for consideration by all shareholders if the proposals conform to certain procedural and substantive requirements.[10] A wide array of groups with social or political agendas—among them “social investing” funds seeking more than share-price returns, politicians overseeing public-employee investment funds, and groups of nuns pursuing their vision of the Christian gospel—have long sought to leverage this process to influence corporate behavior.

Until recently, these efforts never succeeded in persuading a majority of shareholders to support social activists’ agenda. In the decade from 2006 through 2015, companies in the Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor database faced 1,347 shareholder proposals principally involving social or policy goals; not a single such proposal received majority shareholder support over board opposition. In 2016, a proposal at Fluor seeking additional disclosures of corporate spending on politics received the support of a slight majority of shareholders. And in 2017, as discussed, both ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum saw shareholder majorities support climate-change-related proposals. (A third company in the Proxy Monitor database that fell outside the 2016 Fortune 250, PPL, also saw a shareholder majority support a similar shareholder-sponsored climate-change proposal.)

On Sept. 8, 2017, the office of the New York City comptroller launched its “Boardroom Accountability 2.0” campaign, designed to “ratchet up the pressure on some of the biggest companies in the world to make their boards more diverse, independent, and climate-competent.”[11] Democrat Scott Stringer—since 2014, New York City’s elected comptroller—oversees five pension funds for city employees. During the past three years, the comptroller’s office successfully campaigned for “proxy access,” which would grant shareholders—given ownership and holding-period requirements—the power to nominate board directors on the company’s proxy statement. Among the 151 companies that Stringer targeted for the coming 2018 proxy season, 139 previously adopted proxy-access rules.

This report reviews the 2017 proxy season to shed light on these trends. Section I looks at shareholder incidence and overall voting success. Section II looks at the sponsors of shareholder proposals. Section III looks at the subject matter of shareholder proposals. An Appendix looks at shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation, as well as votes on the frequency of such advisory votes, as required by the Dodd-Frank Act.[12]

I. Shareholder-Proposal Incidence and Summary Voting Data

In 2017, the average Fortune 250 company faced 1.24 shareholder proposals on its proxy ballot, down from 1.26 last year and 1.32 in 2015 (Figure 1). The number of shareholder proposals remains below the level seen before 2011. From 2006 and 2010, large companies regularly faced shareholder proposals seeking shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation (10% of all shareholder proposals in the period). Beginning in 2011, such advisory votes were required by Dodd-Frank,[13] which obviated any need for further shareholder proposals on that topic.

Among the 226 Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings by Aug. 31, 2017, only 5% of shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders—down from 7% last year and 11% in 2015 (Figure 2).[14] In part, this decrease is attributable to most companies facing a proxy-access proposal agreeing to adopt such a rule rather than contesting a shareholder-proposal on the subject.

II. Shareholder-Proposal Sponsors

Under current SEC rules, even very small shareholders can submit proposals on publicly traded companies’ proxy ballots, if they have held at least $2,000 in company shares for at least one year.[15] In 2017, as has been the case historically, a limited group of shareholders has submitted the overwhelming majority of shareholder proposals (Figure 3). This group includes:

- Corporate gadflies.[16] A few individuals, along with their family members, repeatedly file substantially similar proposals across a broad set of companies. Typically, these individual investors hold relatively small amounts of stock. In 2017, just three individuals and their family members—John Chevedden, the father-son team of William and Kenneth Steiner, and the husband-wife team of James McRitchie and Myra Young—sponsored 25% of all shareholder proposals.

- Social-policy investors. Certain institutional investors tend to file shareholder proposals oriented around social or policy agendas with an attenuated relationship to share value. Among these are “socially responsible” investing funds[17] that expressly concern themselves with more than just share-price maximization, as well as policy-oriented foundations and various retirement and investment vehicles associated with religious or public-policy organizations. This class of investors sponsored 46% of shareholder proposals in 2017.

- Labor-affiliated pension funds. Pension funds and other investment vehicles affiliated with organized labor regularly sponsor shareholder proposals. Among these are “multiemployer” pension plans affiliated with labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO); and state and municipal pension plans, particularly those representing New York City and State. This class of investors sponsored 19% of all shareholder proposals in 2017.

Individual investors apart from Chevedden, the Steiners, and McRitchie/Young sponsored 9% of shareholder proposals in 2017, though many of these could also be classified as “gadfly” investors with histories of repeated shareholder activism. In keeping with historical norms, only 1% of shareholder proposals in 2017 were sponsored by institutional investors without a social or policy orientation or an affiliation with organized labor.

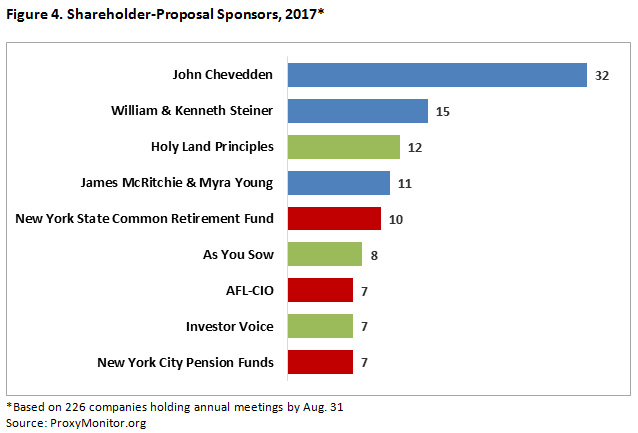

As was the case in 2016 and the full 12-year period dating back to 2006, John Chevedden was the most active sponsor of shareholder proposals in 2017—proposing 32 that made the ballots of Fortune 250 companies (Figure 4). The Steiners were the second-most active shareholder-proposal sponsors, and McRitchie and Young the fourth-most active. In 2017, Chevedden made the same voting-rights-related proposal at Ford Motor Company that he has made in each of the 12 years covered in the Proxy Monitor database; he owns approximately 0.00001% of the company’s stock.

The third-most active sponsor of shareholder proposals in 2017—and the most active social- or policy-focused sponsor—was Holy Land Principles, Inc. This is a nonprofit entity seeking to push companies to develop a code of conduct for employment practices in Israel and the Palestinian territories,[18] and its shareholder proposals have been exclusively focused on this topic. Other active socially oriented sponsors of shareholder proposals include the umbrella groups As You Sow and Investor Voice; large numbers of social-investing funds and Catholic orders filed a small number of shareholder proposals as well.

Labor-affiliated investors’ sponsorship of shareholder proposals in 2017 is down—from 21% in 2006 and 32% across the decade from 2006 to 2015. The AFL-CIO remains among the nine most active sponsors of shareholder proposals, but at least some of the private labor plans appear to have taken a less active role in sponsoring shareholder proposals than in earlier years, reflecting a possible shift in strategy. The pension plans for New York State and City remain among the most active sponsors of shareholder proposals and were the fifth- and ninth-most active sponsors, respectively, in 2017. Moreover, these totals understate the aggressive role undertaken by the New York City pension funds, which withdrew a large fraction of its shareholder proposals relating to proxy access as companies decided to adopt a proxy-access rule rather than contest the issue.

III. Shareholder-Proposal Subjects

Shareholder proposals can vary in type but can be classified depending on function (Figure 5):

- Corporate governance proposals focus on the rules governing the election, composition, or structure of boards of directors, or on shareholders’ powers to act independent of board meetings or action. This class of proposal constituted 36% of all shareholder proposals in 2017.

- Executive-compensation proposals seek to change the manner in which companies compensate senior executives, purportedly to better align management’s incentives with shareholders’ interests or to achieve other goals. In 2017, 8% of all shareholder proposals involved executive compensation.

- Social or policy proposals involve a goal beyond share value, though such proposals are often couched in terms of companies’ reputational risks or “sustainability.” These proposals constituted 56% of all shareholder proposals in 2017.

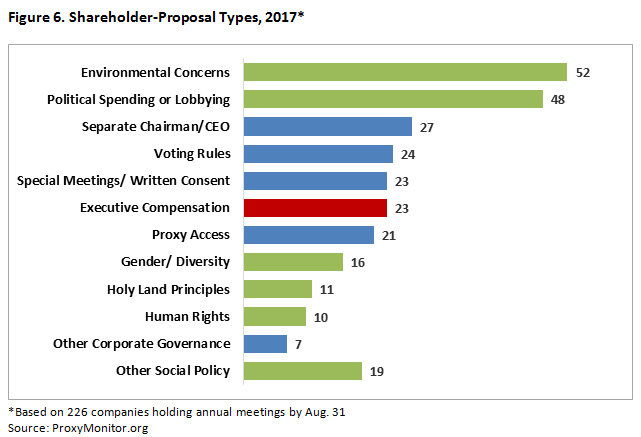

As was the case in 2016 and the prior decade, more shareholder proposals in 2017 involved environmental concerns than any other single type of proposal (Figure 6). Most of these involved greenhouse gas emissions, “portfolio risk” from climate-change regulation, or more general sustainability concerns. The second-most common type of shareholder proposal, as in 2016, involved a company’s political spending or lobbying.

Apart from these two most common types of social-oriented proposals, most shareholder proposals involved executive compensation or one of four corporate governance issues: (1) separating the company’s chairman and chief executive roles; (2) voting rules for director elections or shareholder actions; (3) shareholder powers to call special meetings or to act outside annual meetings by written consent; and (4) shareholder powers to nominate directors on corporate proxy ballots (proxy access). Less common but still regularly introduced social and policy proposals included those involving gender/diversity, employment practices in Israel, and human rights.

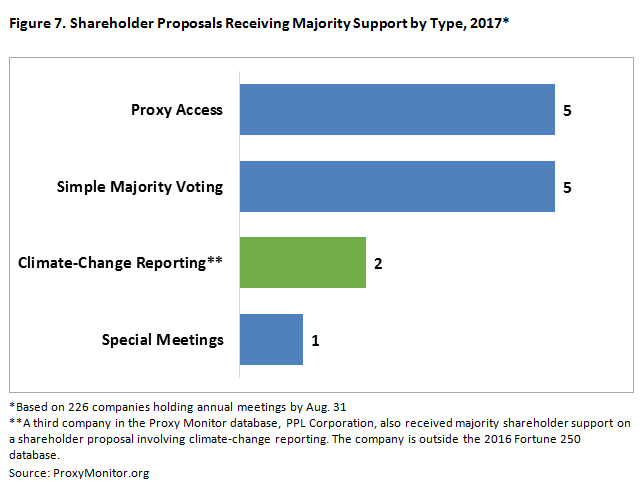

Only four types of shareholder proposals received majority shareholder support in 2017 (Figure 7):

- Proxy-access proposals (five of 21 proposals coming to a vote)

- Proposals seeking to authorize all corporate actions by simple majority vote (five of six proposals)

- Proposals asking for a report on the portfolio impact of climate-change regulations (two of seven proposals)

- Proposals seeking to empower shareholders to call special meetings (one of 15 proposals)

Shareholder support for eliminating supermajority voting requirements from bylaws is consistent with recent years. The percentage of proxy-access-related proposals to win majority shareholder support understates shareholder support on the issue. As discussed, many companies facing such a proposal in 2017 adopted their own proxy-access rule rather than face a contested shareholder vote on the subject. In addition, a majority of all proxy-access-related shareholder proposals in 2017 sought to loosen proxy-access requirements for companies that had already adopted a rule. Among those companies facing a proxy-access proposal that had not already adopted a rule, only two—PACCAR and Tyson Foods—saw a majority of shareholders vote against the proposal. (Tyson has a two-class stock structure that gives founding shareholders significant voting control.)

Appendix

Mandatory Shareholder Votes Advising on Executive Compensation and Voting Frequency

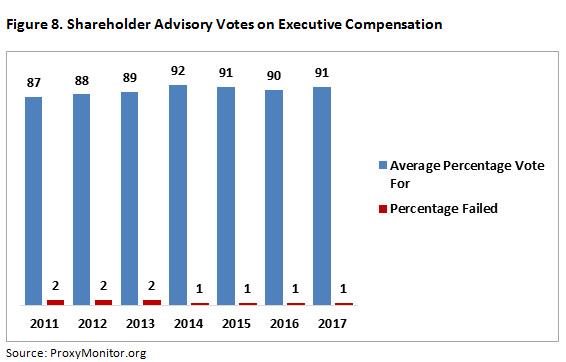

Since 2011, federal law has mandated that shareholders hold advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially.[19] Shareholders at most companies have opted to hold such votes annually. In 2017, 223 companies in the Fortune 250 met by Aug. 31 and held shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation.

For most large companies, management’s executive-compensation packages remain very likely to garner majority shareholder support in advisory votes (Figure 8). Among the 223 Fortune 250 companies holding an advisory vote on executive compensation in the first eight months of 2017, a majority of shareholders voted against management at only two companies: McKesson (26% support for management) and ConocoPhillips (32%). On average, 91% of shareholders at Fortune 250 companies supported management in executive-compensation votes in 2017, consistent with historical trends.

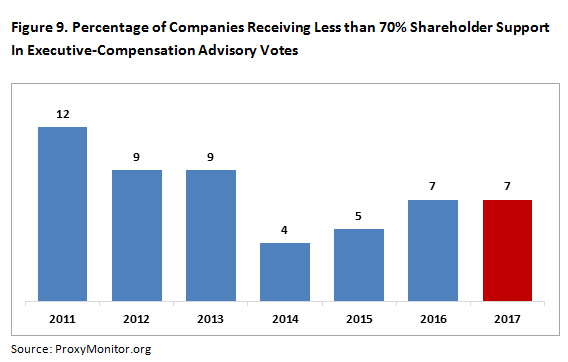

The largest proxy advisory firm, Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), has determined that any company that fails to win the support of at least 70% of shareholders in executive-compensation advisory votes needs to address compensation issues—and otherwise warrants a closer look in its vote the following year.[20] (This arbitrary cutoff is somewhat circular, given the percentage of the shareholder vote influenced on average by ISS’s own recommendations.)[21] In 2017, 7% of companies failed to win the support of at least 70% of shareholders in executive-compensation advisory votes, consistent with 2016 (Figure 9).

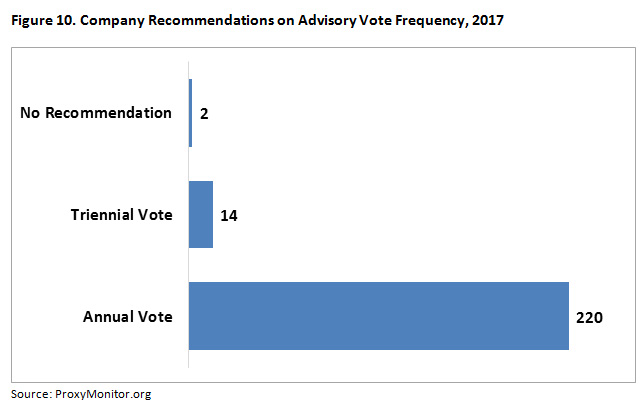

Under the terms of Dodd-Frank, companies are required every six years to return to shareholders to solicit their advice on how regularly to hold shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation. Most companies held these votes first in 2011—and again in 2017. Given that most shareholders supported annual votes on executive compensation in 2011, most companies recommended annual votes in 2017 (Figure 10). Two companies in the Proxy Monitor database made no recommendation in 2017, and shareholders in each company supported annual voting rights. The boards of 14 companies recommended triennial voting in lieu of annual votes. For the most part, shareholders nevertheless supported annual voting. A majority of shareholders supported annual advisory votes—against the board recommendation—at five of the 14 companies: Amazon, Dollar General, INTL FC Stone, Nucor, and PACCAR. Although triennial voting received majority shareholder support at the other nine companies, each had dual-class stock ownership or large, if not majority, insider holdings.

Endnotes

- Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders’ discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010) [hereinafter Dodd-Frank Act].

- See Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings.

- Those companies are: Applied Materials, Ashland, Avon, Coca-Cola Enterprises, Dean Foods, GameStop, Genworth Financial, HCA Holdings, ITT, KBR, Motorola Solutions, Oshkosh, Principal Financial Group, and Public Service Enterprise Group.

- Those companies include AMR, Aon, Constellation Energy, Coventry Health Care, Dell, Eaton, Hillshire Brands, H.J. Heinz, Medco, Smithfield Foods, Sunoco, URS, and US Airways.

- See Heidi Welsh, Accuracy in Proxy Monitoring, HLS Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, Sept. 16, 2013 (critiquing the Proxy Monitor database).

- See Liam Kennedy, Top 400 Asset Managers 2016: Global Assets Now €56.3trn, INVESTMENT & PENSIONS EUROPE (June 2016).

- Bethany McLean, The Backstory Behind That "Fearless Girl" Statue on Wall Street, THE ATLANTIC, Mar. 13, 2017.

- See Kennedy, supra note 6.

- Emily Chasan, BlackRock Finds Shareholder Action Goes Both Ways, BLOOMBERG BRIEFS, Mar. 16, 2017.

- See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007) [hereinafter 14a-8].

- Office of the New York City Comptroller, Comptroller Stringer, NYC Pension Funds Launch National Boardroom Accountability Project Campaign—Version 2.0, Sept. 8, 2017.

- SeeDodd-Frank Act, supra note 1.

- See id.

- In determining shareholder support for shareholder proposals, the Manhattan Institute counts votes consistent with the practice dictated in a company’s bylaws, consistent with state law. Some companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of votes for a proposal by the total number of shares present and voting, ignoring abstentions. Other companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of favorable votes by the number of shares present and entitled to vote—thus including abstentions in the denominator of the tally. Neither practice necessarily skews shareholder votes in management’s favor: whereas the latter method makes it relatively more difficult for shareholder resolutions to obtain majority support, it also makes it more difficult for management to win shareholder backing for its own proposals, such as equity-compensation plans.

Some shareholder-proposal activists and their advocates prefer to exclude abstentions consistently in tabulating vote totals, without regard to corporate bylaws; see Welsh, Accuracy in Proxy Monitoring. This metric necessarily inflates apparent support for shareholder proposals. But such a methodology is inconsistent with state and federal law. The SEC’s Schedule 14A specifies that for “each matter which is to be submitted to a vote of security holders,” corporate proxy statements must “[d]isclose the method by which votes will be counted, including the treatment and effect of abstentions and broker non-votes under applicable state law as well as registrant charter and bylaw provisions”—clearly indicating that corporations can adopt varying counting methodologies in assessing shareholder votes and that state substantive law governs the parameters of vote calculation. See Item 21, Voting Procedures, 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-101. Under the state law of Delaware, where most large public corporations are chartered, “the certificate of incorporation or bylaws of any corporation authorized to issue stock may specify the number of shares and/or the amount of other securities having voting power the holders of which shall be present or represented by proxy at any meeting in order to constitute a quorum for, and the votes that shall be necessary for, the transaction of any business.” Del. Gen. Corp. L. § 216. As a default rule, absent a bylaw specification, Delaware law specifies that “in all matters other than the election of directors,” companies should count “the affirmative vote of the majority of shares of such class or series or classes or series present in person or represented by proxy at the meeting,” id. at 216(4)—the precise inverse of shareholder-proposal activists’ preferred counting rule.

The SEC staff has adopted a permissive standard that “[o]nly votes for and against a proposal are included in the calculation of the shareholder vote of that proposal,” ignoring abstentions, SEC Staff Legal Bulletin No. 14, F.4., July 13, 2001; but only for the very limited purpose of determining whether a proposal has met the “resubmission threshold” to qualify for inclusion on the next year’s corporate ballot—a minimum 3%, 6%, or 10%, respectively, in successive years. See Amendments to Rules on Shareholder Proposals, Exchange Act Release No. 40,018; 63 Fed. Reg. 29,106, 29,108 (May 28, 1998) (codified at 17 C.F.R. pt. 240). Because this is a staff rule not voted on by the commission, because it exists for a limited purpose (with multiple rationales, including reducing workload in processing 14a-8 no-action petitions and adopting a permissive standard for ballot inclusion), and because it contravenes clear and long-standing deference to substantive state law in the field of corporate governance, the notion that this limited SEC staff vote-counting rule should dictate counting methodology, irrespective of state law and governing corporate bylaws, is untenable.

- See 14a-8, supra note 10.

- “Corporate gadflies,” as commonly used in Charles M. Yablon, Overcompensating: The Corporate Lawyer and Executive Pay, 92 COLUM. L. REV. 1867, 1895 (1992); and Jessica Holzer, Firms Try New Tack Against Gadflies, WALL ST. J., June 6, 2011.

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, FORBES, Apr. 24, 2013 (“In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about.”).

- See Holy Land Principles, Inc., About Holy Land Principles.

- See Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 1, at § 951.

- If a company falls below 70% support, then ISS expects its board to respond to investors’ concerns and, if insufficiently satisfied, the proxy advisor will punish the company in future say-on-pay vote recommendations as well as, potentially, by withholding support for the company’s nominees for director serving on the compensation committee. See ISS, 2017 United States Summary Proxy Voting Guidelines: 2017 Benchmark Policy Recommendations 13, 42 (Dec. 22, 2016).

- See James R. Copland et al., Proxy Monitor 2012: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism, 22–23 (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Fall 2012) (showing 19-percentage-point impact on executive-compensation advisory voting given ISS “for” recommendation).