Before joining MI, Copland was a management consultant with McKinsey and Company in New York. Earlier, he was a law clerk for Ralph K. Winter on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Copland has been a director of two privately held manufacturing companies since 1997 and has served on many public and nonprofit boards. He holds a J.D. and an M.B.A. from Yale University, where he was an Olin Fellow in Law and Economics; an M.Sc. in the politics of the world economy from the London School of Economics; and a B.A. in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was a Morehead Scholar. Copland owns a diversified investment portfolio that may include, in small-percentage concentrations, the equities of companies named in this or other Proxy Monitor reports.

Although the November election upended political expectations in Washington, corporate America’s “proxy season” is proceeding apace and not dissimilarly from the norm in recent years. From late April to early June, most large publicly traded corporations in the United States hold annual meetings to vote on company business. In the first quarter of 2017, 28 of America’s 250 largest publicly traded companies by revenues, as ranked by Fortune magazine, held their annual meetings. Twelve more will have met through April 23—followed by 32 more in the last week of April. By June 15, most of America’s 250 largest publicly traded companies will have met to conduct their business.

“Proxy season” gets its moniker from the proxy statements distributed by companies to their equity shareholders, which, for publicly traded companies, contain disclosures required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)[1]; as well as the proxy ballots through which shareholders can vote on issues of corporate concern presented to them. Some such issues involve business presented to shareholders by corporate boards—including the election of directors and selection of corporate auditors—but shareholders can also place resolutions on the proxy. Under current SEC rules, these shareholder resolutions can be introduced by any shareholder holding equity valued at $2,000 or more for at least one year.[2]

Although shareholders may not intervene in the ordinary business of the corporation, the SEC has tended to give a rather broad berth to shareholders in recent decades. Under current SEC interpretive guidance, shareholder proposals are presumptively valid if they “involve any substantial policy or other considerations,”[3] unless they are “not significantly related to the business of the issuer or not within its control.”[4] Thus, in recent years, shareholders interested in concerns other than share value—including social and policy issues of general concern—have regularly utilized the shareholder-proposal rules to try to influence corporate behavior.

This report gives a final review of shareholder-proposal activism in the 2016 proxy season and previews the 2017 season. Empirical evidence is based on data in the Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor database, available online at ProxyMonitor.org, which catalogs shareholder proposals submitted to the 250 largest U.S. publicly traded companies (see box).[5] Key findings include:

- A very small number of shareholders sponsor most shareholder proposals. In 2017, three shareholders—John Chevedden, Kenneth Steiner, and James McRitchie—have sponsored more than one-third of all shareholder proposals.

- Most shareholders are not engaged in shareholder-proposal activism. In 2016 and 2017 to date, no institutional investor has sponsored a shareholder proposal, except for those affiliated with a labor union or public-employee pension plan or those with a social-investing, public-policy, or religious purpose. Such institutional investors have sponsored only 1% of all shareholder proposals dating back to 2006.

- Shareholder activism related to social and policy concerns is up. In 2016, a majority of all shareholder proposals involved social or policy concerns with an attenuated connection to share value.

- Most large publicly traded companies are adopting proxy access, but they have some scope in how to structure these rules. Following a substantial shareholder-proposal effort by the New York City pension funds to prod companies to adopt “proxy access”—allowing shareholders holding a certain fraction of company stock for a certain period to place director nominees on company proxy ballots—most large companies are responding to shareholder sentiment and adopting proxy-access rules. However, companies have been able to adopt rules that are less permissive than those sought by some shareholder activists. In 2017, multiple shareholder proposals seeking to adopt more permissive standards than those selected by the company have been introduced, thus far without attracting majority shareholder support.

- No shareholder proposal has received majority support to date in 2017. Among the 28 Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings in the first quarter of 2017, none has seen a shareholder proposal receive majority shareholder support.

Section II of this report summarizes shareholder-proposal activity in 2016, with a focus on who sponsored the proposals, their subject matter, and voting results. Section III previews the 2017 season, based on the 72 Fortune 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled by April 30 and the early voting results at the 28 of those companies that had held annual meetings by March 31. Section IV highlights upcoming annual meetings at which shareholder-proposal items of interest are coming up for a vote in the last week in April: proxy-access proposals, proposals relating to corporate political spending or lobbying, proposals to separate corporate chairman and CEO positions, proposals seeking to modify various shareholder voting rules, and proposals seeking to empower shareholders to call special meetings or act by written consent.

About Proxy Monitor

The Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive-advisory votes[6] at America’s largest companies. The database is overseen by Margaret M. O’Keefe, who has more than two decades’ experience in executive-compensation, corporate-governance, and proxy-advisory consulting. This is the seventh annual report previewing the annual proxy season by Manhattan Institute’s program on legal policy, directed by James R. Copland. This report and other reports and findings in the Proxy Monitor series draw upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-proposal process.[7]

|

II. 2016 Proxy Season Review

Number of Proposals

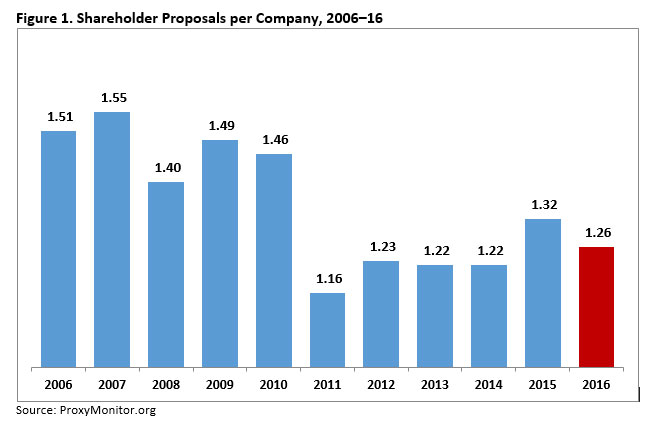

The average Fortune 250 company faced 1.26 shareholder proposals, on average, in 2016—down slightly from 2015 but more than in any other year since 2010 (Figure 1). (The decline in the number of shareholder proposals since 2010 is explained by the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act that year.[8] Dodd-Frank mandated that companies hold annual, biennial, or triennial shareholder-advisory votes on executive compensation; this obviated shareholder proposals seeking such votes, which had been commonplace prior to the statute.) Overall, the 250 largest American companies faced 315 shareholder proposals in 2016, down from 330 in 2015 but up from 305 in 2014 and 306 in 2013.

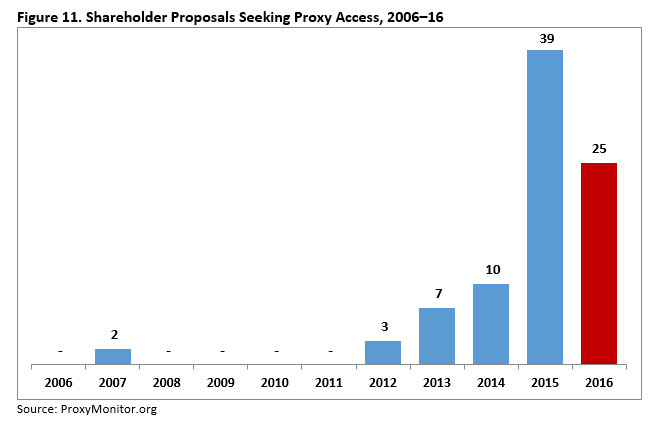

The year-over-year drop in the number of shareholder proposals is attributable to different corporate behavior in response to shareholder proposals seeking “proxy access,” the idea that shareholders should have the right to place their own nominees for director on corporate proxy ballots to compete with boards’ own director nominees. In November 2014, the office of New York City comptroller Scott Stringer—an elected official who oversees the pension fund assets that underlie retirement benefits for the city’s public employees[9]—announced that proxy access would be the linchpin of the new “Boardroom Accountability Project” purportedly designed “to ensure that companies are truly managed for the long-term.”[10] In 2015, the New York City funds introduced shareholder proposals seeking proxy access at 75 companies.[11] Although the comptroller’s office again introduced 72 proxy-access proposals in 2016, companies receiving these proposals were much more likely to adopt their own proxy-access proposal—and negotiate with the proposal sponsor to withdraw the proposal—after most such proposals received majority shareholder support the preceding year. Thus, the number of proxy-access shareholder proposals actually filed on Fortune 250 companies’ proxy ballots fell from 39 in 2015 to 25 in 2016.

Voting Results

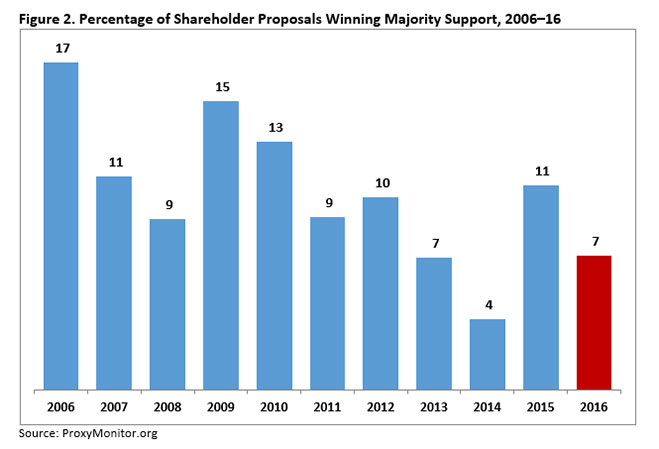

In 2016, 7% of shareholder proposals received majority shareholder support, down from 11% in 2015 but up from 4% in 2014 (Figure 2). These shifts in support are also attributable to proxy-access proposals. Less than 4% of shareholder proposals excluding proxy-access proposals received majority shareholder support in either 2015 or 2016.

Proposal Sponsors

In 2016, as in each of the 10 preceding years in the Proxy Monitor database, a small group of shareholders sponsored most shareholder proposals:

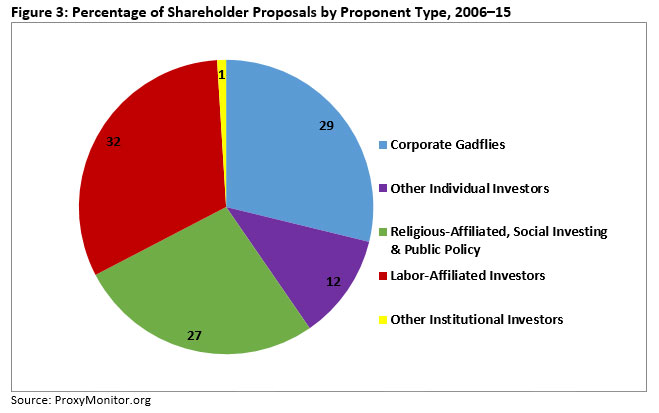

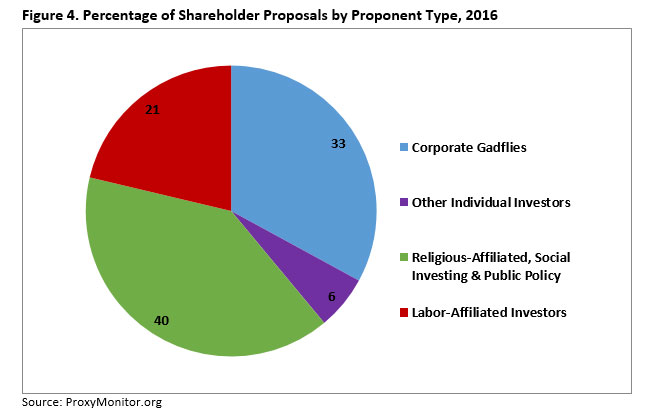

- Corporate gadflies. Small investors commonly called “corporate gadflies” regularly file common proposals, on their own or in conjunction with family members and family trusts, at large numbers of publicly traded companies.[12] The five most active gadfly investors sponsored 29% of all shareholder proposals in the 2006–15 period (Figure 3). In 2016, the six most active gadflies and their family members—John Chevedden; William Steiner (and son Kenneth); James McRitchie (and wife, Myra Young); John Harrington (who also introduces proposals through his social-investing fund, Harrington Investments); Gerald Armstrong; and Jonathan Kalodimos (a new corporate gadfly in 2016)—sponsored 33% of all shareholder proposals (Figure 4).

- Social investors. A variety of institutional investors that focus on “socially responsible” investing,[13] as well as various retirement and investment vehicles associated with religious or public-policy organizations, are active sponsors of shareholder proposals. Unsurprisingly, these investors tend to sponsor shareholder proposals more focused on issues of broad social, political, or economic concern than with traditional issues relating to corporate governance. In the 2006–15 period, these social-oriented investors sponsored 27% of all shareholder proposals. That percentage rose to 40% in 2016.

- Labor-affiliated investors. Two kinds of labor-affiliated pension funds commonly sponsor shareholder proposals: “multiemployer” plans affiliated with labor unions, such as the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO); and state and municipal pension plans holding assets in trust for public employees, such as the New York City pension funds. (Corporate-sponsored private pension plans almost never file shareholder proposals.) In total, labor-affiliated pension plans sponsored 21% of shareholder proposals introduced at Fortune 250 companies in 2016—down from 32% annually over the prior decade and 28% in 2015. This decline is attributable to fewer ballot proposals on proxy access sponsored by the New York City pension funds—owing to companies’ decisions to moot the proposal by adopting their own proxy-access rule—as well as less activity among private multiemployer pension plans affiliated with labor unions, continuing a recent trend.

Aside from this small group of shareholder-proposal activists, very few stockholders introduce proposals on corporate proxy ballots. Institutional investors without a connection to public- or private-employee pensions or a social, religious, or policy orientation sponsored no shareholder proposals in 2016 and less than 1% of all shareholder proposals in the preceding 2006–15 decade.

The three most active sponsors of shareholder proposals in 2016 were the corporate gadflies Chevedden, Steiner, and McRitchie, who, among them, sponsored 68 shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies (Figure 5). After these gadfly investors, the most frequent sponsors of shareholder proposals were investment vehicles associated with the AFL-CIO and its multiemployer pensions and the social-investing vehicle Newground Social Investment.[14] Two other investors sponsored eight proposals each: the New York State Common Retirement Fund and Holy Land Principles (the latter a newly formed nonprofit entity seeking to push companies to develop a code of conduct for employment practices in areas governed by Israel and the Palestinian Authority).[15] As discussed, the New York City pension funds were significantly more active in sponsoring shareholder proposals than their raw total—six proposals sponsored—would suggest; most companies facing a proxy-access proposal sponsored by the New York City pension funds in 2016 adopted their own proxy-access rule and negotiated with the city comptroller’s office to withdraw the proposal.

Proposal Subject Matter

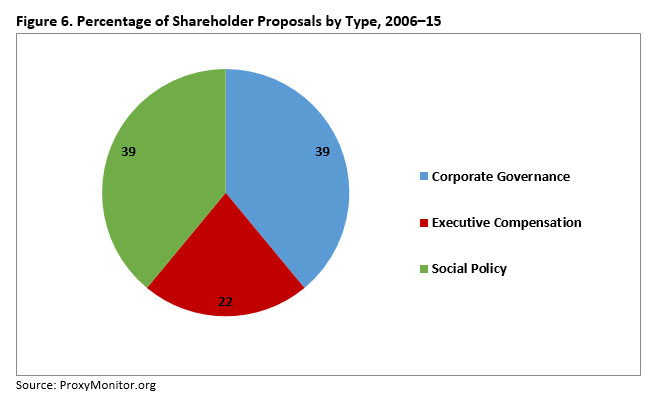

Historically, shareholder proposals have been evenly split between those focusing on corporate governance questions (such as proxy access, rules for electing directors or taking other shareholder actions, and other questions of board structure and governance) and those involving social or policy concerns with only an attenuated connection to shareholder value (such as disclosure of corporate political spending or lobbying, environmental issues, and human rights). Each of these broad classes of proposal constituted 39% of all proposals over the decade from 2006 through 2015 (Figure 6). Proposals relating to executive compensation constituted 22% of all shareholder proposals in the period.

In 2016, the fraction of shareholder proposals devoted to social and policy issues was well above prior norms: a majority of all shareholder proposals focused on these issues (Figure 7). Thirty-eight percent of all shareholder proposals last year focused on corporate governance questions, and 11% on executive compensation. The percentage of shareholder proposals related to executive compensation is down, as compared with the 2006–15 period, largely because proposals seeking shareholder-advisory votes on executive compensation, which were commonly introduced through 2010, were mooted by Dodd-Frank’s rule mandating such votes.[16]

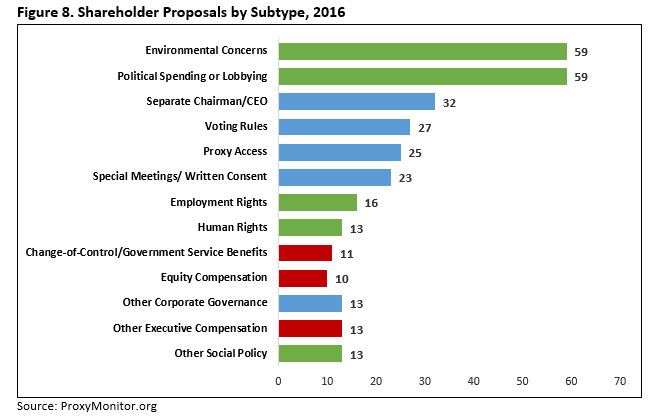

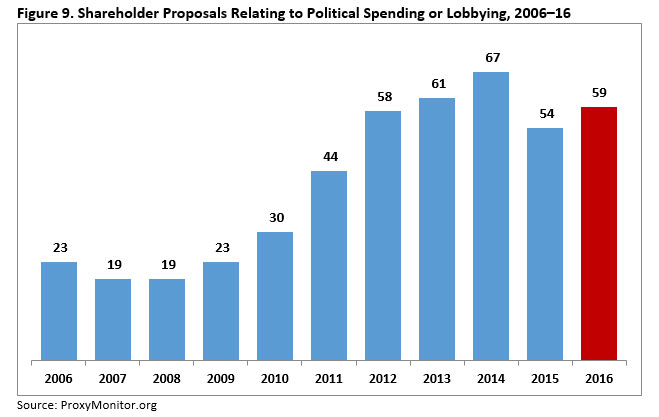

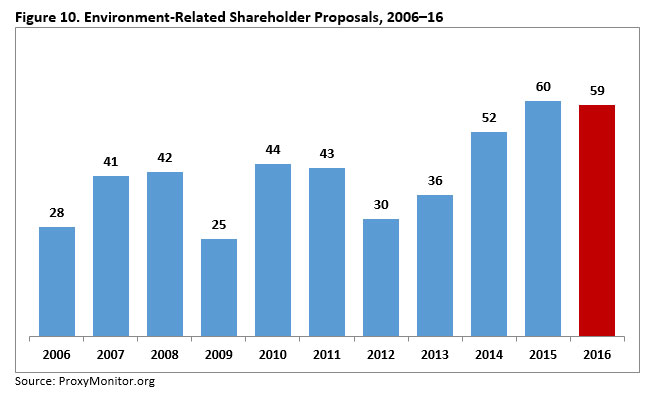

Looking at narrower groupings of shareholder proposals, the most common types of proposal involved environmental concerns, corporate political spending or lobbying, and separating the company’s chairman and chief executive roles (Figure 8)—types of proposals seen commonly throughout the broader 2006–15 period. There were somewhat more shareholder proposals relating to corporate political spending or lobbying in 2016 than 2015, though still considerably below the peak year in 2014 (Figure 9). Shareholder proposals involving environmental issues also remained common in 2016; the 59 proposals related to this subject were just one below a record year for activity in 2015 (Figure 10). Proxy-access proposals remained common in 2016, though somewhat less so than in 2015, when they were first sponsored en masse by the New York City pension funds (Figure 11); again, this fall in proxy-access proposal sponsorship is more attributable to companies’ decisions to adopt their own proxy-access policies and negotiate with sponsors to withdraw their shareholder proposals.

Voting Results by Proposal Type

Among the 22 shareholder proposals to receive majority shareholder support at Fortune 250 companies in 2016, 13 involved proxy access (Figure 12). By comparison, 26 proxy-access proposals received majority votes in 2015—thus explaining the year-over-year decline in the percentage of shareholder proposals receiving majority support (from 11% in 2015 to 7% in 2016). Excluding proxy-access proposals, just over 3% of 2016 shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders. One of those, though receiving majority shareholder support, failed: it was structured as an amendment to the company’s certificate of incorporation and required unanimous support. Another shareholder proposal received majority support after it was endorsed by the company’s board of directors: an animal-rights proposal at Kellogg that did no more than applaud the company for switching to eggs produced by cage-free chickens. Thus, overall among Fortune 250 companies, only seven precatory shareholder proposals involving issues other than proxy access “passed” over board opposition in 2016.

Executive-Compensation Advisory Votes

Since 2011, U.S. publicly traded companies have held advisory shareholder votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, as required under the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. Shareholders at most companies have opted to hold these votes annually. A majority of shareholders have voted in favor of executive compensation at 98% or more of Fortune 250 companies in each of the last six years. In 2016, shareholders voted disapproval for executive compensation at four Fortune 250 companies: Bed Bath & Beyond, Community Health Systems, Exelon, and Oracle. The first three companies’ votes were discussed in more detail in the fall 2016 Proxy Monitor report.[17] A majority of shareholders voted disapproval of Oracle’s executive compensation for the fifth consecutive year; CEO and founder Larry Ellison owns more than one-quarter of the company’s outstanding shares.

III. 2017 Early Filings and Voting Returns

In the first three months of 2017, 28 publicly traded Fortune 250 companies held annual meetings. These companies faced 25 shareholder proposals that came up for a vote.

Another 44 companies are holding annual meetings in April 2017. Of these, 42 are holding meetings in the last two weeks of the month, and 32 in the last week of April alone, as proxy season begins in earnest.

Thus, by the end of April, 72 of the Fortune 250 companies will have held their annual meetings. These early filing data shed some light on the 2017 proxy season—though historically, early filing data do not necessarily reflect the full picture of the proxy season, which will become clearer once the companies that are meeting in May—the heart of the proxy season—have filed their proxy statements.

Early Filing Data

The 72 Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings by April 30, 2017, will have faced 79 shareholder proposals—1.10 per company, on average. In comparison, the average company faced 1.26 shareholder proposals in all of 2016. These early returns, however, may not be illustrative; the comparable early period in 2016 saw 1.42 shareholder proposals per company, but the comparable period in 2015 and 2014 saw only 0.96 and 0.98 shareholder proposals per company, respectively.

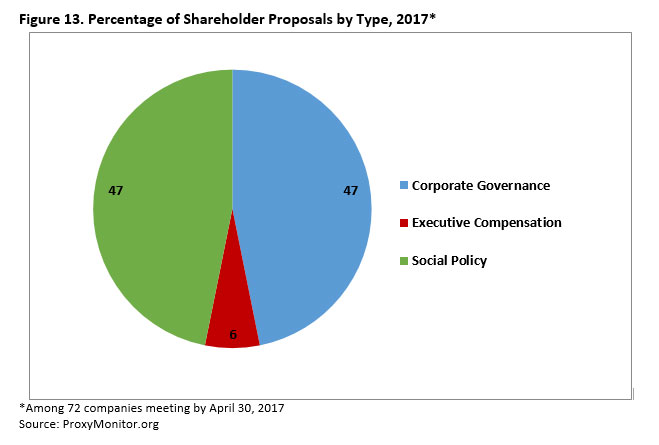

Among early-meeting companies, proposals are evenly split between those relating to corporate governance (47%) and those relating to social-policy concerns (47%) (Figure 13). Only 6% of proposals to date have involved executive compensation. By comparison, the total mix of shareholder proposals in 2016 skewed somewhat more heavily toward social-policy issues (51%).

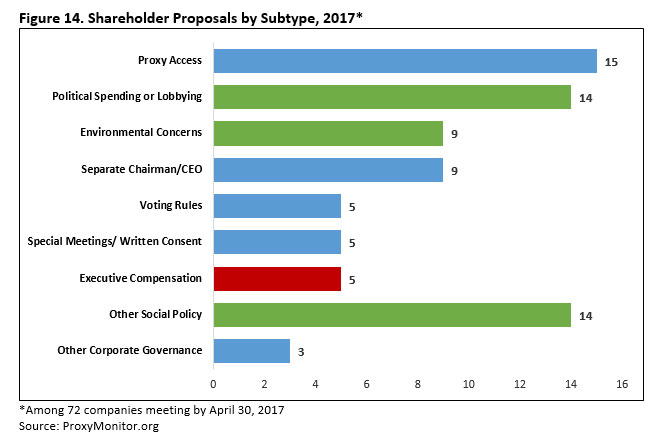

The increased prevalence of shareholder proposals related to corporate governance has been driven principally by an increased number of proposals related to proxy access. In 2015, a wave of proxy-access proposals was introduced, chiefly by the New York City pension funds. The number of such proposals making proxy ballots dropped in 2016 because most companies agreed to adopt a proxy-access rule on their own, prompting the proposal sponsor to withdraw the proposal. The resurgence in proxy-access-related proposals in 2017 has been driven by proposals seeking to modify companies’ already-adopted proxy-access rule in favor of a more permissive standard; such proposals are a majority of those relating to proxy access this year. Overall, a plurality of proposals (15) have related to proxy access, with 14 relating to corporate political spending or lobbying, nine relating to environmental concerns, and nine seeking to separate the company’s chairman and CEO roles (Figure 14). The percentage of shareholder proposals relating to environmental issues can be expected to rise when May proxy statements are incorporated into the data, as most of the large oil and gas concerns hold annual meetings later in the proxy season.

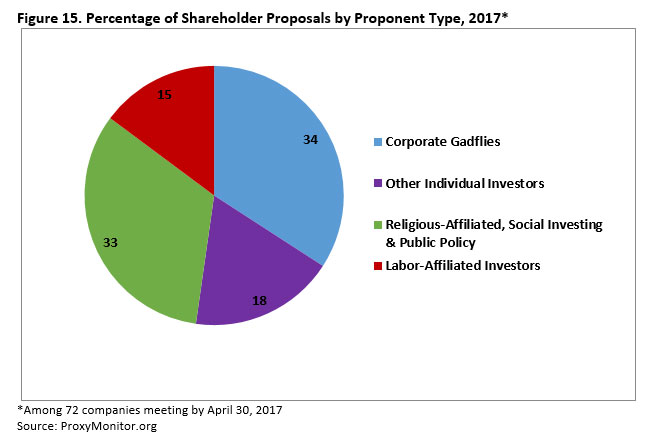

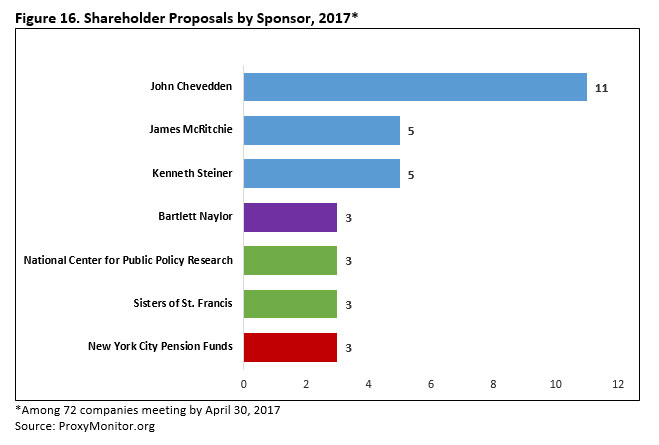

To date in 2017, three corporate gadflies—John Chevedden, James McRitchie, and Kenneth Steiner—have filed more than one-third of all shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies (Figure 15). Among the 18% of all proposals sponsored by other individual investors, some were sponsored by other traditionally active gadflies, Gerald Armstrong and John Harrington. Three 2017 proposals to date were sponsored by Bartlett Naylor, a 61-year-old staffer at Public Citizen who, in recent years, has emerged as a gadfly of large financial institutions, introducing proposals designed to encourage big banks to break up (Figure 16).[18] If Armstrong, Harrington, and Naylor are included among the corporate gadflies, those six gadfly investors have sponsored more than 44% of all shareholder proposals.

Almost one-third of all 2017 shareholder proposals filed for companies holding annual meetings have been sponsored by institutional investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation. As is often the case, there are many more investors active in this class; most have filed just one or two proposals to date. Two investors with a policy or religious orientation have sponsored three proposals to date: the conservative National Center for Public Policy Research, which has sponsored proposals prodding companies to review their approaches to charitable giving and human rights; and the Sisters of St. Francis, an order of nuns that has sponsored proposals asking companies to separate their chairman and CEO roles, as well as a proposal asking Wells Fargo to assess reputational risks flowing from the bank’s retail banking sales practices.

Labor-affiliated investors have traditionally focused their efforts later during the main proxy season. The New York City pension funds have introduced three shareholder proposals at companies meeting through the end of April, two seeking proxy access and one asking NRG Energy to produce a report on its political spending.

Early Voting Results

Twenty-eight Fortune 250 companies had held 2017 annual meetings by the end of March, holding votes on 34 shareholder proposals. None of those shareholder proposals received the support of a majority of shareholders; indeed, none received the support of even 40% of shareholders. On average, more than 78% of shareholders voted against each shareholder proposal on company proxy ballots. Nine shareholder proposals received the support of 30%–40% of shareholders: three seeking to amend the company’s proxy-access rules in favor of a more permissive standard for shareholders to nominate directors, three seeking additional corporate disclosures concerning political spending or lobbying, one seeking to separate the company’s chairman and CEO, one seeking to empower shareholders to act by written consent, and one seeking a report on food waste (at Whole Foods).

Executive-Compensation Advisory Votes

In 2017, through the end of March, a majority of shareholders voted for each Fortune 250 company’s executive compensation. The average shareholder support was just under 92%, slightly above the 90% average for all of 2016. More than 90% of shareholders have supported executive compensation at 81% of companies, up from 72% in all of 2016—and more than in any complete year since compensation advisory votes began en masse in 2011.

Only two companies to date have received less than 70% shareholder support, the level at which the proxy-advisory firm ISS expects a company response to registered shareholder disapproval with compensation: AECOM and Johnson Controls. AECOM, meeting on March 1, received the support of just 52% of shareholders in its executive-compensation advisory vote. This marked the third consecutive year that the company’s say-on-pay voting support declined; the company noted in its proxy statement that it had consulted with shareholders representing a majority of shares, reduced executive-compensation levels, and added a relative total stockholder return metric in setting executive pay.[19] At Johnson Controls, meeting on March 8, more than 36% of shareholders voted disapproval for the company’s executive compensation. Shareholders may have been registering disapproval of executive payouts stemming from the company’s August 2016 reverse merger with Tyco International.[20]

Also, in 2017, most companies have had to resolicit shareholder opinion on whether executive votes should be held annually, biennially, or triennially, as required under Dodd-Frank—including all but seven of the 72 Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings by the end of April. Among the 22 companies holding votes on how often to hold executive-compensation advisory votes by the end of March, 19 recommended annual shareholder-advisory votes; 88%–97% of shareholders agreed with these board recommendations. The boards of three companies—the financial-services firm INTL FCStone, the food company Tyson Foods, and the media conglomerate Viacom—recommended triennial votes. Tyson and Viacom each have two-tiered stock-ownership structures that give effective voting control to the Tyson founding heirs[21] and Sumner Redstone’s National Amusements,[22] respectively; 95% of Viacom’s voting shareholders and 79% of Tyson’s voted with the board recommendation. At INTL FCStone, only 40% of shareholders supported the board recommendation.[23]

IV. Upcoming Meetings to Watch

In the last two weeks of April 2017, 42 Fortune 250 companies are holding annual meetings. These 42 companies face a total of 52 shareholder proposals; eight face three or more shareholder proposals: AT&T, Bank of America, Citigroup, General Electric, IBM, Marathon Petroleum, Pfizer, and Wells Fargo (Wells Fargo faces six, and AT&T, Citigroup, and GE each face four).

Nine of these late-April proposals involve corporate political spending or lobbying, eight involve proxy access, seven seek to separate the company’s chairman and chief executive officer roles, five involve voting rules, and four seek to empower shareholders to call special meetings or act through written consent.

Political Spending and Lobbying

In the last week of April, eight Fortune 250 companies face nine shareholder proposals involving corporate political spending or lobbying. These proposals were sponsored by the New York State Common Retirement Fund, the New York City Employees’ Retirement System, the Philadelphia Public Employee Retirement System, the labor-union-affiliated Change-to-Win investment group, the social-investing fund Walden Asset Management, and the socially oriented Nathan Cummings Foundation.

- Honeywell—April 24

- Citigroup—April 25

- IBM—April 25

- Wells Fargo—April 25

- General Electric—April 26

- Textron—April 26

- NRG Energy—April 27

- AT&T—April 28

AT&T faces two separate proposals, one involving corporate political spending and one involving corporate lobbying. NRG’s proposal involves disclosure of political spending but not lobbying; all other companies’ proposals involve lobbying.

Proxy Access

Eight Fortune 250 companies face shareholder proposals relating to proxy access in the last two weeks of April. These proposals were sponsored by the New York City pension funds and corporate gadflies John Chevedden and James McRitchie.

- AES Corporation--April 20

- Humana--April 20

- IBM—April 25

- PACCAR—April 25

- Cigna—April 26

- Edison International—April 27

- AT&T—April 28

- Kellogg—April 28

The proposals at IBM and PACCAR were each sponsored by the New York City pension funds, and each asks the board to adopt a proxy-access rule modeled on the SEC’s former rule. Each company’s board has opposed the proposal; the New York City funds also introduced a proxy-access proposal at PACCAR in both 2015 and 2016, each of which failed to garner majority shareholder support. Cigna and Humana also face proposals asking the board to adopt a proxy-access rule; each company has opposed the proposal, and Cigna in its proxy statement states that the board intends to formulate its own proxy-access rule and submit it to shareholders at the 2018 annual meeting. The proposals at AES, Edison, AT&T, and Kellogg each seek to modify an existing proxy-access rule already adopted by the board. AES's and Edison’s proposals are sponsored by John Chevedden, Edison's would allow up to 50 shareholders to aggregate shares to hit the company’s required 3% ownership threshold to nominate directors (up from 20 in the company’s existing rule), and AES's would allow any number of shareholders to aggregate shares; proposals at AT&T and Kellogg, sponsored by James McRitchie, would allow any number of shareholders to aggregate shares to hit the threshold.

Splitting Chairman and CEO Roles

Six shareholder proposals seeking to separate companies’ chairman and CEO positions are going to be considered by shareholders at Fortune 250 companies’ meetings in the last week of April. (A seventh was introduced at U.S. Bancorp, which will be meeting on April 18, before this report’s release but after it went to press.) These proposals were sponsored by corporate gadflies Kenneth Steiner, Gerald Armstrong, and John Chevedden; by a fund operated by the Teamsters Union; and by the pension fund for the Catholic order the Sisters of St. Francis.

- Honeywell—April 24

- Bank of America—April 26

- General Electric—April 26

- Johnson & Johnson—April 27

- Pfizer—April 27

- Abbott Laboratories—April 28

Honeywell, General Electric, and Johnson & Johnson received similar proposals in 2016; Johnson & Johnson received one as well in 2015, and Honeywell has received one every year dating back to 2012. None of these has received majority shareholder support.

Voting Rules

Five Fortune 250 companies meeting in the last week of April face shareholder proposals, sponsored by various gadfly and individual investors, that ask the board to modify various shareholder voting rights.

- BB&T—April 25

- PACCAR—April 25

- Wells Fargo—April 25

- General Electric—April 26

- Marathon Petroleum—April 26

The proposals at PACCAR and Marathon Petroleum seek to require prospective directors to receive a majority of shareholder votes in uncontested director elections to be seated to the board. The proposals at Wells Fargo and General Electric seek a rule that would permit “cumulative voting,” i.e., allowing shareholders to cast more than one director vote for a single director nominee, up to the number of outstanding board seats being contested. The proposal at BB&T seeks to eliminate all supermajority voting provisions in the company bylaws.

Special Meetings/Written Consent

Four Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings in the last week of April face shareholder proposals sponsored by corporate gadflies John Chevedden and Kenneth Steiner that seek shareholder rights to call special meetings or act through written consent.

- IBM—April 25

- HCA Holdings—April 27

- Pfizer—April 27

- AT&T—April 28

IBM, HCA, and Pfizer each face Chevedden-sponsored proposals seeking to permit 10% of outstanding shareholders to call a special meeting. IBM and Pfizer already have a rule permitting 25% of shareholders to call such a meeting; HCA has proposed a competing 25% special-meeting rule in its 2017 proxy. AT&T faces a proposal by Steiner to permit a majority of shareholders to act by written consent.

V. Conclusion

Despite the sea change in Washington’s policy environment, the 2017 proxy season thus far looks to be “business as usual.” To date, there is no observable uptick in the number of shareholder resolutions and no increase in shareholder support for resolutions. Indeed, at least for the large companies in the Proxy Monitor database, the push for proxy access has largely run its course. Most large companies are adopting proxy-access rules, and the major activity in 2017 surrounds shareholder efforts to revise existing proxy-access standards in favor of more relaxed standards—so-called fix-it efforts, which, to date, have failed to garner majority shareholder support.

The main proxy season beginning in late April will shed light on whether most shareholders continue to reject shareholder proposals related to political spending or lobbying. In 2016, a majority of shareholders of the Texas-based Fluor Corporation supported a shareholder resolution calling for increased disclosures of corporate political spending, which the company subsequently executed.[24] The Fluor vote is the only instance over the last 11 years in which a majority of shareholders supported a political-spending-related shareholder proposal, and the average shareholder support for political-spending and lobbying proposals has remained below 25%, with no noticeable uptick. The 2017 proxy votes will shed significant light on whether the 2017 Fluor vote was indeed an outlier.

Although the percentage of environment-related shareholder proposals introduced in 2017 to date is below that in recent years, this trend should reverse when the large oil and gas companies file their proxy statements; these companies tend to hold annual meetings later in May. As observed in the 2016 Proxy Monitor report, last year “five environmental-policy proposals received at least 40% shareholder support—as compared to only two in the entire decade from 2006 through 2015.”[25] The extent to which this trend continues in 2017 will be interesting to observe—especially in light of a new administration in Washington that places significantly less regulatory emphasis on climate change than its predecessor. Such a shift may be expected to increase the activity of shareholder-proposal activists seeking to influence through corporate governance what they cannot influence through ordinary legislative and regulatory channels—though increased filings, if any, may not be observable until 2018, given that the 2016 presidential-election results were largely unexpected. In shareholder voting, however, the shift in Washington might encourage less support for shareholder resolutions involving climate change, assuming that institutional investors are voting as fiduciaries focused on share value: regulatory risks involving climate change, which are the principal rationale connecting the issue to shareholders’ interests,[26] are significantly lower today than they were in 2016.

Finally, outside the proxy season itself, the new leadership of the SEC, once confirmed, may take some interest in various regulatory matters that affect shareholder-proposal activity, and they may choose to review various issues relating directly to that process. In June 2014, the SEC staff promulgated a legal bulletin clarifying how its rules applied to proxy advisors,[27] but Congress has been looking at this issue in more detail; 2016 legislation advanced in the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services would subject proxy-advisory firms to greater oversight.[28] The House has also held hearings on reforming the 14a-8 shareholder-proposal process, including one in September 2016, at which this report’s primary author testified.[29] In addition to the proxy season itself, we will be watching legislative and regulatory developments closely in 2017.

Endnotes

- Although corporate governance in the U.S. is mostly governed by substantive state law, cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”); the federal SEC controls the process of proxy solicitation under rules promulgated under section 14(a) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, 4, Pub. L. No. 73-291, ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934).

- See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007).

- See Adoption of Amendments Relating to Proposals by Security Holders, Exchange Act Release No. 12,999, 41 Fed. Reg. 52,994, 52,997–98 (1976).

- See Exchange Act Release No. 9784, 37 Fed. Reg. 23,178, 23,180 (1972). Notably, this interpretation inverts the SEC’s prior rule, which permitted companies to exclude from proxy ballots shareholder proposals that were introduced “primarily for the purpose of promoting general economic, political, racial, religious, social, or similar causes.” Exchange Act Release No. 4775, 17 Fed. Reg. 11,431, 11,433 (1952).

In 1970, the U.S. Court of Appeals remanded to the SEC for further consideration the no-action letter that the agency had granted to Dow Chemical permitting it to exclude a shareholder proposal seeking to have the company cease producing napalm, then in use in the Vietnam War. The circuit decision did not strike down the SEC’s rule but rather asked the agency to articulate a rationale so that “the basis for [its] decision [may] appear clearly on the record, not in conclusory terms but in sufficient detail to permit prompt and effective review.” See Med. Comm. for Human Rights v. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, 432 F.2d 659, 682 (D.C. Cir. 1970). Dow decided to include the proposal on its proxy ballot, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari to review the case, vacating the D.C. Circuit opinion as moot. See 404 U.S. 403 (1972).

- Cf. Fortune 500.

- Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder-advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders’ discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010) [hereinafter “Dodd-Frank Act”].

- See Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings.

- See Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 6.

- See Office of the State Comptroller, Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller. Full fiduciary authority over the funds rests with various boards composed of political and union delegates. For example, the board of the $43 billion New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) includes the comptroller, the public advocate, a mayoral representative, each of the five New York City borough presidents, and three union delegates. See NYCERS, Board of Trustees.

- New York City Comptroller, Boardroom Accountability Project; see also Press Release, Comptroller Stringer, NYC Pension Funds Launch National Campaign to Give Shareowners a True Voice in How Corporate Boards Are Elected: New York City Pension Funds File 75 Proxy Access Shareowner Proposals to Kick Off the Boardroom Accountability Project, Nov. 6, 2014.

- See id.

- “Corporate gadflies,” as commonly used in Charles M. Yablon, Overcompensating: The Corporate Lawyer and Executive Pay, 92 COLUM. L. REV. 1867, 1895 (1992); and Jessica Holzer, Firms Try New Tack Against Gadflies, WALL ST. J. (June 6, 2011).

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, FORBES (Apr. 24, 2013) (“In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about”).

- Newground sponsored proposals relating to political spending and the environment; but most of its proposals have focused on trying to push companies to modify bylaw rules that tabulate the percentage vote for shareholder proposals. Under Newground’s preferred vote-counting rule, the number of shareholder votes “for” a proposal should be divided by the number of votes “for” or “against” to calculate percentage support; many companies instead calculate voting support based on Delaware’s default rule, which divides votes “for” by all voting proxies, including abstentions. (Of course, Newground’s preferred vote-counting rule would increase the apparent shareholder support for social-oriented, as well as other, shareholder proposals.)

- See Holy Land Principles, Inc.: About Holy Land Principles.

- See Dodd-Frank Act, supra note 6.

- See James R. Copland & Margaret M. O’Keefe, Proxy Monitor 2016: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism, Manhattan Inst., at App., pp. 28–29.

- See Hugh Son, Bicycle-Riding Bank Antagonist Naylor Scores Two Proxy Proposals, BLOOMBERG, Mar. 19, 2015.

- See AECOM, Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Jan. 17, 2016), at 1–2.

- See Johnson Controls, Inc., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of

the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (July 6, 2016). The reverse merger relocated the company’s corporate headquarters to Ireland. As such, the new Johnson Controls International will not be in the Fortune 250 beginning with this year’s list and will no longer be included in Proxy Monitor analyses after 2017.

- Tyson has two classes of stock, with Class B shares, controlled by the founding family, having 10 votes per share. The founding family’s ownership of both Class A and B shares gives them effective 70% voting control of the company.

- Only 10% of Viacom’s outstanding equity comprises Class A shares with voting rights; 80% of these voting shares are owned by National Amusements, according to the National Amusements website.

- INTL FCDStone is an unusual company in the Proxy Monitor database, with a market capitalization of less than $1 billion. It is listed in the Fortune 500 owing to the way its commodities-derivatives business books revenues, which forms the basis of Fortune’s list.

- See Mitchell Schnurman, Shareholders Pushed Irving's Fluor Corp. to Reveal Its Political Spending, and Here’s What They Found, DALLAS MORNING NEWS, Mar. 14, 2017.

- See Copland and O’Keefe, supra note 17, at 25.

- See, e.g., James R. Copland, Against an SEC-Mandated Rule on Political Spending Disclosure: A Reply to Bebchuk and Jackson, 3 HARV. BUS. L. REV. 381, 399 n. 66 (2013) (“[E]ven if the costs imposed by climate change risks per se would be minimal to shareholders, given reasonable stock-market discount-rate assumptions, the legislative and regulatory risks related to climate change concerns could be quite significant to many businesses. Thus, a mandatory disclosure rule related to climate change, unlike that for political spending, would seem to meet a basic materiality threshold”).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Proxy Voting: Proxy Voting Responsibilities of Investment Advisers and Availability of Exemptions from the Proxy Rules for Proxy Advisory Firms, Staff Legal Bulletin no. 20 (IM/CF) (June 30, 2014).

- See Press Release, Duffy Advances Corporate Governance Reform Bill, June 16, 2016.

- See James R. Copland, Testimony Before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on SEC Rule 14a-8, Sept. 21, 2016.