PROXY MONITOR 2016

FINDING 2

Environmental Issues

By James R. Copland and Margaret M. O’Keefe

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute’s Proxy Monitor database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive-compensation advisory votes[1] at America’s largest publicly traded companies. The database is overseen by Margaret M. O’Keefe, who has more than two decades’ experience in executive-compensation, corporate-governance, and proxy-advisory consulting. This is the 38th publication in a series of findings and reports written solely or jointly by Manhattan Institute legal-policy director James R. Copland, each drawing upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-proposal process[2].

|

Introduction

Environmental activists last year stepped up efforts to target companies in the energy sector in a coordinated campaign,[3] assisted by legal attacks against Exxon Mobil launched by state attorneys general and the attorney general of the U.S. Virgin Islands.[4] In addition, as has been the case for many years, shareholder activists who are focused on social and environmental concerns have targeted publicly traded companies with shareholder proposals placed on company proxy ballots under rules promulgated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[5] Under such rules, shareholders may place items on ballots to be voted on in corporate annual meetings if they have owned $2,000 or more company shares for at least one year.[6]

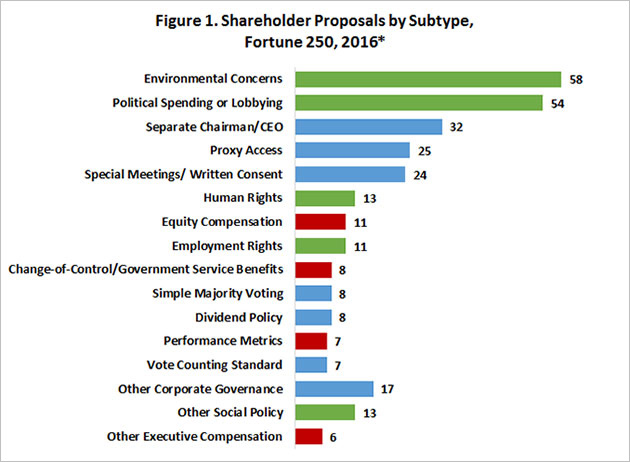

As in 2015, a plurality of shareholder proposals in 2016 have involved environmental concerns (Figure 1).[7] These proposals addressed issues including climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, “sustainability,” recycling, water quality, genetically modified organisms (GMO), fossil fuels, nuclear power, and methane emissions. Some of these proposals ask the board of directors to produce a report—including on general environmental concerns—and others seek specific actions such as lowering greenhouse gas emissions or labeling GMO products.

*228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

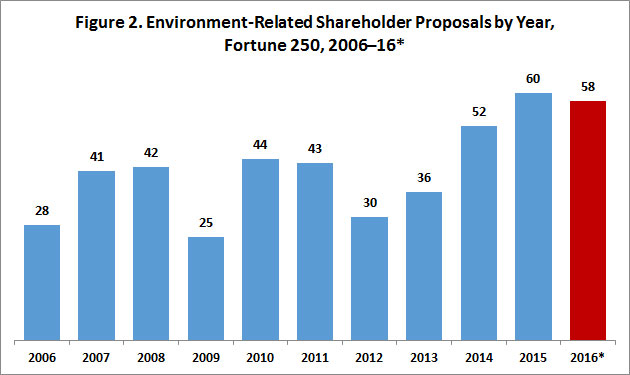

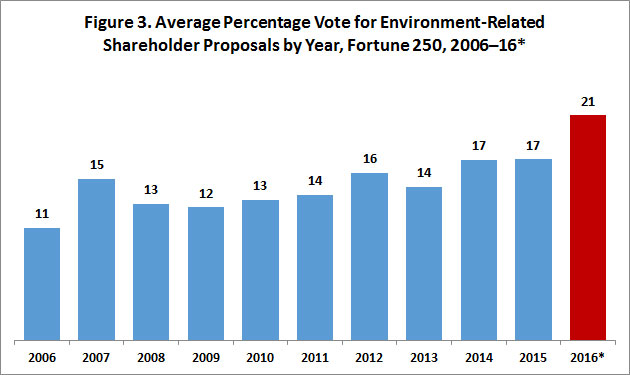

The number of environment-related proposals has been rising in recent years, and 2016—with 228 of 250 Fortune 250 companies having filed proxy statements to date—is on pace to set a record (Figure 2). For all years covered in the Proxy Monitor database, not a single environment-related shareholder proposal has received majority shareholder support over board opposition; however, the average shareholder vote for such proposals is up in 2016 (Figure 3).[8] In addition, five environment-related shareholder proposals received at least 40 percent shareholder support (a record number); four of these five proposals involved climate change or greenhouse gas emissions. Overall, the 23 shareholder proposals related to climate change or greenhouse gas emissions voted on to date at Fortune 250 companies in 2016 received the support of 26 percent of shareholders, up from 16 percent support in 2015 and 14 percent during 2006–15. This finding explores the recent push by certain shareholders in light of overall climate-change activism and examines the 2016 proxy-access proposals and voting results in historical context.

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 219 of 250 companies holding annual meetings by June 10

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

Focus: Environment-Related Shareholder Activism

Background

Responding to pressure from certain shareholder activists, the SEC in 2010 adopted guidelines requiring publicly traded corporations to make new disclosures related to “climate risks.”[9] Since then, however, shareholder activists who are focused on environmental concerns have continued applying pressure on corporations through shareholder proposals. In November 2015, New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman announced an investigation of Exxon Mobil over its funding of research related to climate change. On January 8, 2016, various environmental activists and members of the Rockefeller family attended a closed-door meeting in Manhattan with the stated goal of “establish[ing] in the public’s mind that Exxon is a corrupt institution,” “delegitimize[ing] [Exxon] as a political actor,” and “driv[ing] Exxon & climate into [the] center of [the] 2016 election.”[10]

Shortly thereafter, California attorney general Kamala Harris, who is seeking election to the U.S. Senate in November, announced her own climate-change investigation parallel to Schneiderman’s. Other state attorneys general followed suit, as well as Virgin Islands attorney general Claude E. Walker.[11] Some of these attorneys general also sought documents from various nonprofit groups that had published research and opinion on climate change. Thus, although proposals relating to climate change, global warming, and greenhouse gas emissions have long been the subject of shareholder-proposal activism, the 2016 proxy season began with a very different backdrop.

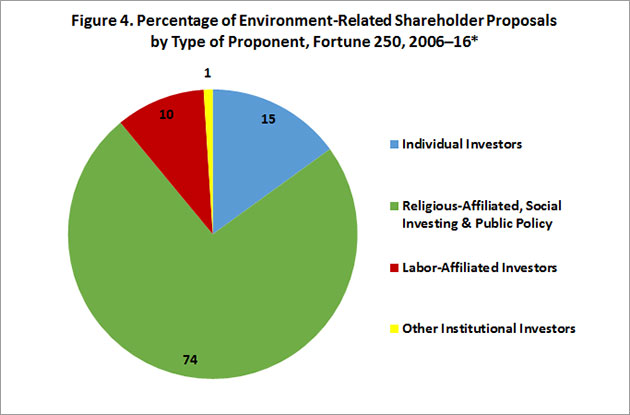

Environment-Related Shareholder Proposal-Activism: 2006–16

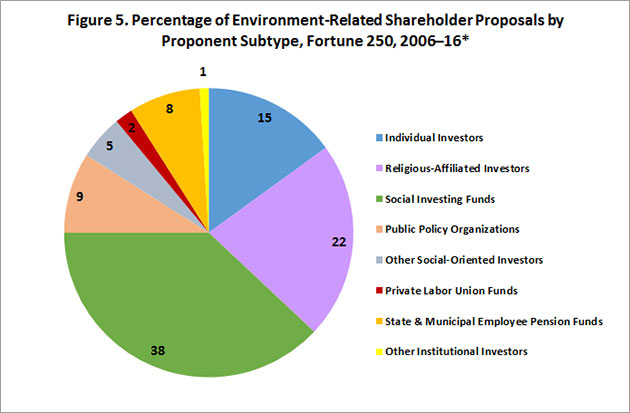

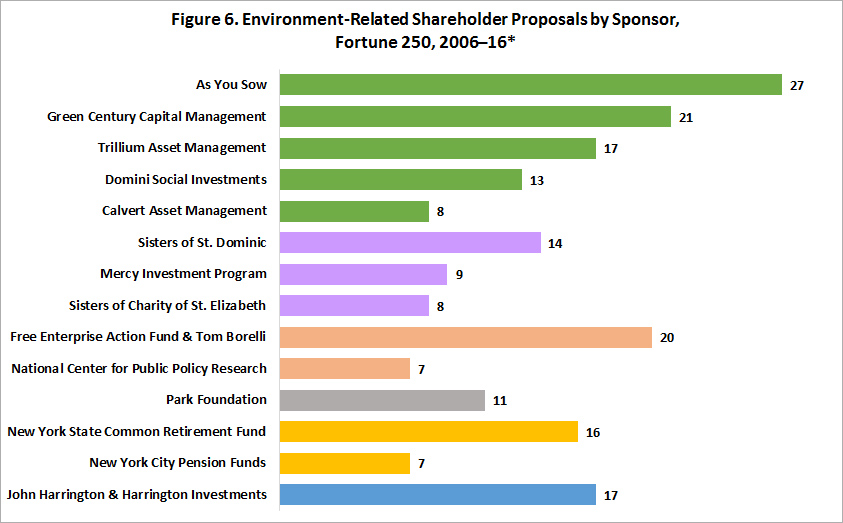

Since 2006, the first year covered in the Proxy Monitor database, the vast majority of shareholder proposals involving the environment (74 percent) have been sponsored by shareholders with a social, religious, or environmental purpose (Figure 4). Social-investing funds—which focus on “socially responsible investing,” with an express purpose beyond maximizing share value[12]—have sponsored 38 percent of environment-related shareholder proposals over the period (Figure 5). Religious-affiliated investors—typically, the pension funds of Catholic orders of nuns or other church-based institutions[13]—have sponsored 22 percent of shareholder proposals in that time; and investment vehicles affiliated with public-policy organizations have sponsored 9 percent. The most active sponsors among these social-oriented investors have been the umbrella social-investment nonprofit As You Sow, which explicitly focuses on shareholder-proposal activism;[14] the social-investing funds Green Century Capital Management and Trillium Asset Management; the Catholic order Sisters of St. Dominic; and the Free Enterprise Action Fund, a policy-oriented investment vehicle organized by free-market advocate Tom Borelli (Figure 6). Other investors particularly active in sponsoring environment-related shareholder proposals include John Harrington, a “corporate gadfly” individual investor who also has a social-investing fund; and the New York State Common Retirement Fund, which holds assets in trust for the New York State & Local Retirement System.

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

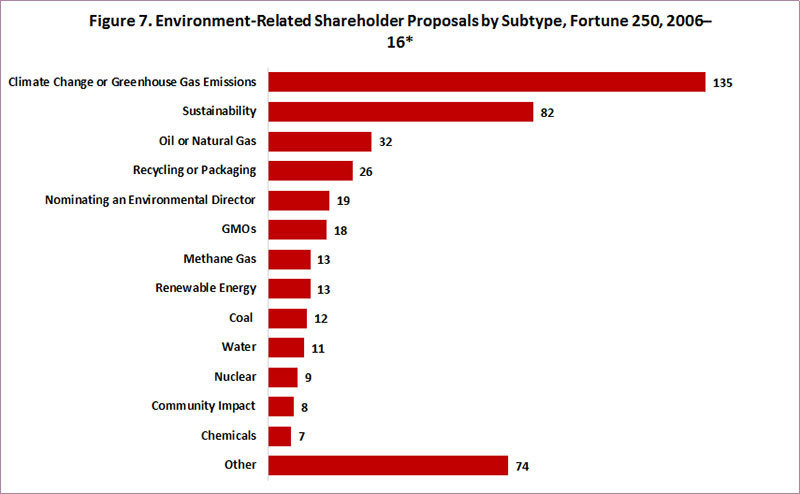

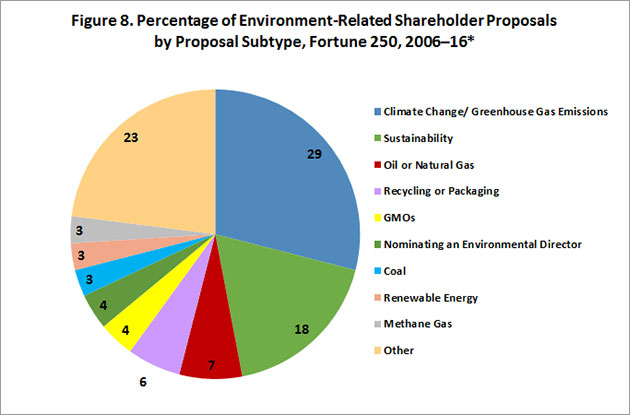

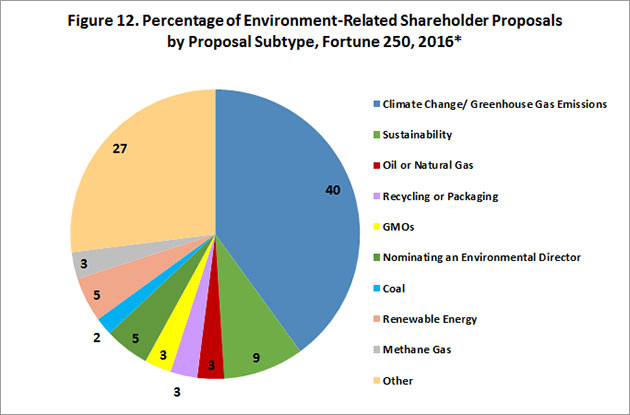

During 2006–16, a plurality of all environment-related shareholder proposals have concerned climate change, global warming, or greenhouse gas emissions (Figure 7). Typically, these proposals have called on the board of directors to promulgate a report on global warming or climate change, including related financial risks to the company; or to set targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The second-most introduced class of environmental proposal has looked more generally at “sustainability,” a vague environmental concept described as “creat[ing] and maintain[ing] the conditions under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony to support present and future generations.”[15] These types of reports have most often called on the board to issue a report on sustainability or to set up a board committee governing the subject. Taken together, climate change and sustainability have been the focus of 47 percent of all shareholder proposals related to the environment (Figure 8).

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

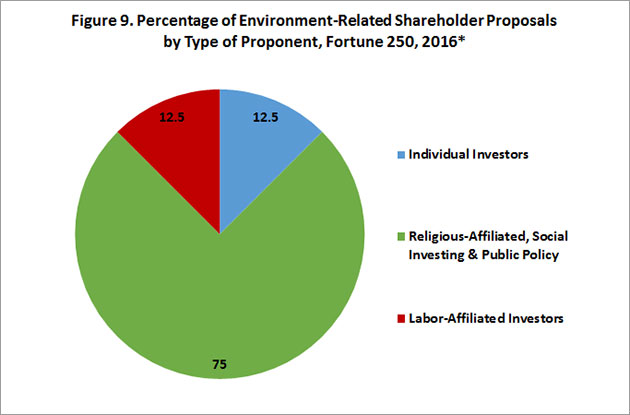

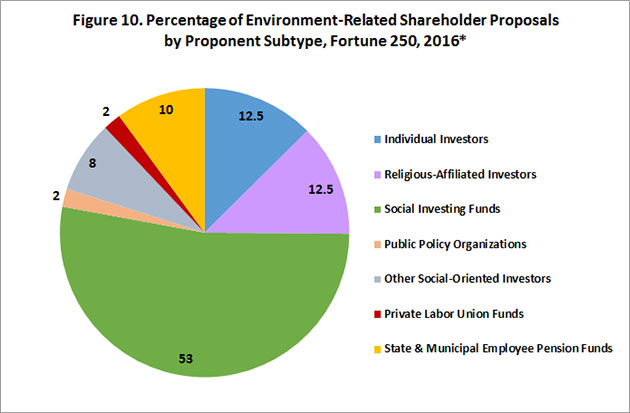

In 2016, 75 percent of all environment-related shareholder proposals were sponsored by institutional investors with a social-investing purpose or related to a religious or public-policy organization (Figure 9)—in keeping with trends over the broader period, 2006-16 (74 percent). This year, however, social-investing funds have played a larger relative role, sponsoring 53 percent of all environment-related proposals (Figure 10), compared with 38 percent for the period dating to 2006. As You Sow and the New York State Common Retirement Fund have sponsored the most environment-related proposals in 2016 (Figure 11). Forty percent of all shareholder proposals this year have involved climate change or greenhouse gas emissions (Figure 12), up from 29 percent across the 2006–16 period.

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*In 2016, for 228 of 250 companies with annual meetings scheduled through the end of June

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

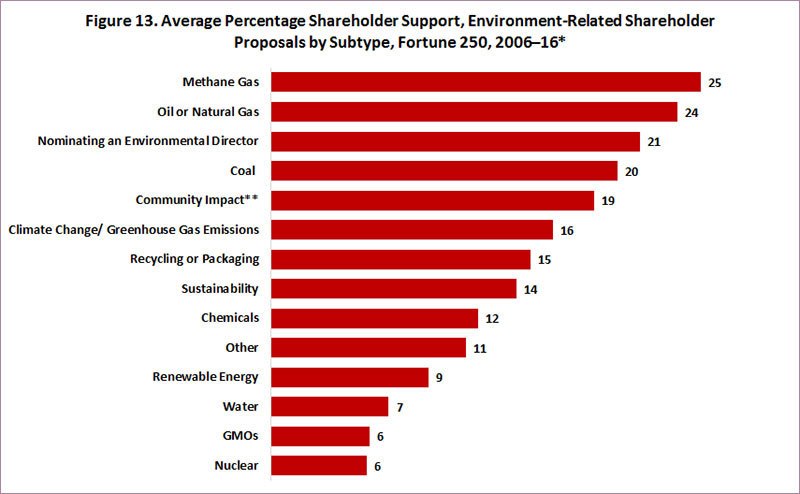

Voting Results and Analysis

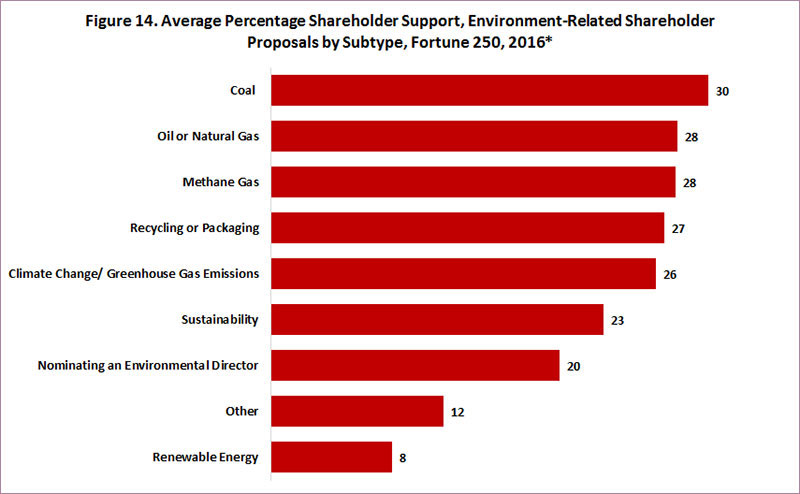

As noted, the average shareholder vote for environment-related proposals is up somewhat in 2016, to 21 percent, from 17 percent in 2015 (and 15 percent across the full 2006–16 period). In general, shareholder votes on environment-related proposals have ticked upward across proposal subcategories (Figure 13 and Figure 14). In some cases, these subcategory increases are partly explained by a shift in the proposal mix within the category. For example, proposals related to climate change or sustainability that call for the company’s board of directors to promulgate a report typically are supported by the leading proxy-advisory firm ISS, and they tend to receive significantly more shareholder support than more esoteric proposals focused on the same subject that rarely win proxy-advisory firms’ backing.[16] Shareholder activists are aware of proxy-advisory firms’ positions and previous shareholder voting behavior, and at least some of them adjust their proposal mix over time in response.

*In 2016, for 219 of 250 companies holding annual meetings by June 10

**All but one environment-related proposal focused on “community” issues received less than 11 percent

shareholder support; one was backed by the board of directors and received 91 percent support.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

*219 of 250 companies holding annual meetings by June 10

Source: ProxyMonitor.org database

Although the percentage of shareholders supporting many environment-related proposals ranges between 15 percent and 30 percent, not a single shareholder proposal has received majority shareholder support over board opposition, dating to 2006. Moreover, the shareholder support received by shareholder proposals receiving between 20 percent and 30 percent of shareholder votes is less robust than it might appear. As explored in a 2012 Manhattan Institute Proxy Monitor report, an ISS recommendation that shareholders vote “for” a given shareholder proposal tends to correspond with a 15-percentage-point increase in the shareholder vote for the proposal, controlling for other factors.[17] Support from other proxy-advisory firms, including Glass Lewis, doubtless leads to additional increases in the shareholder vote.

As observed in our earlier study, “Smaller institutional investors, who are more likely to ‘follow’ ISS, place little value on shareholder voting rights themselves—they gain little value from voting ‘better,’ as the broader voter-ignorance literature would suggest.”[18] ISS has generally been much more supportive of environmental proposals than the median shareholder, and it has increased the range of proposals that it has been willing to support over time.[19] Given its business incentives, it is unsurprising that ISS’s recommendations are “systematically biased in favor of shareholder-proposal activism”; “ISS receives significant revenues from social investment vehicles and labor-union pension funds, which gives the company an incentive to favor ‘socially responsible’ investing proposals.”[20]

Notwithstanding this broader systemic shareholder-voting bias created by ISS, the proxy-advisory firm’s recommendations cannot explain the 2016 uptick in support for environment-related proposals: the proxy-advisory firm has not recently modified its guidelines for these proposal classes.[21] Moreover, although the uptick in support for environmental proposals has been modest, substantially more environment-related shareholder proposals in 2016 have received at least 40 percent shareholder support over board opposition: five in total, as compared with only two in all of 2006–15. Four of those five proposals involved climate change or greenhouse gas emissions: two sponsored by the New York State Common Retirement Fund at Fluor Corporation and PPL Corporation, seeking reports on how to lower greenhouse gas emissions; and two by the pension fund for the United Methodist Church at Chevron and Occidental Petroleum, seeking a report discussing the companies’ climate-change policies and assessing the “short- and long-term financial risks of a lower carbon economy.” The increase in shareholder support for these proposals may be related to the extraordinary politicization of these issues by state attorneys general and other activists, and bears watching in the future.

ENDNOTES

- Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder-advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders’ discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010).

- See Reports and Findings, http://www.proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx.

- See, e.g., Amy Harder et al., Exxon Fires Back at Climate-Change Probe, WALL ST. J., Apr. 13, 2016,

http://www.wsj.com/articles/exxon-fires-back-at-climate-change-probe-1460574535 (last visited June 17, 2016).

- See id.

- Although corporate governance in the U.S. is mostly governed by substantive state law, cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”); the federal SEC controls the process of proxy solicitation under rules promulgated under section 14(a) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, 4, Pub. L. No. 73-291, ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934).

- See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007) [hereinafter “14a-8”].

- The 2016 results include 228 of 250 companies to have scheduled annual meetings by the end of June. Sixteen additional companies from earlier years’ Fortune 250 lists, no longer among the 250 largest publicly traded companies, have proxy information listed on the ProxyMonitor.org database but are excluded from this analysis.

- The 2016 voting results include 219 of 250 companies to have held annual meetings by June 10. In determining shareholder support for shareholder proposals, the Manhattan Institute counts votes consistent with the practice dictated in a company’s bylaws, consistent with state law. Some companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of votes for a proposal by the total number of shares present and voting, ignoring abstentions. Other companies measure shareholder support by dividing the number of favorable votes by the number of shares present and entitled to vote—thus including abstentions in the denominator of the tally. Neither practice necessarily skews shareholder votes in management’s favor: whereas the latter method makes it relatively more difficult for shareholder resolutions to obtain majority support, it also makes it more difficult for management to win shareholder backing for its own proposals, such as equity-compensation plans.

Shareholder-proposal activists prefer to exclude abstentions consistently in tabulating vote totals, without regard to corporate bylaws; see Heidi Welsh, Accuracy in Proxy Monitoring, HLS Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation (Sept. 16, 2013), https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2013/09/16/accuracy-in-proxy-monitoring-2 (critiquing the Proxy Monitor data set), which necessarily inflates apparent support for their proposals. But such a methodology is inconsistent with federal law. The SEC’s Schedule 14A specifies that for “each matter which is to be submitted to a vote of security holders,” corporate proxy statements must “[d]isclose the method by which votes will be counted, including the treatment and effect of abstentions and broker non-votes under applicable state law as well as registrant charter and bylaw provisions”—clearly indicating that corporations can adopt varying counting methodologies in assessing shareholder votes and that state substantive law governs the parameters of vote calculation. See Item 21, Voting Procedures, 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-101, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/240.14a-101. Under the state law of Delaware, where most large public corporations are chartered, “the certificate of incorporation or bylaws of any corporation authorized to issue stock may specify the number of shares and/or the amount of other securities having voting power the holders of which shall be present or represented by proxy at any meeting in order to constitute a quorum for, and the votes that shall be necessary for, the transaction of any business.” Del. Gen. Corp. L. § 216, http://delcode.delaware.gov/title8/c001/sc07 (last visited Sept. 11, 2015). As a default rule, absent a bylaw specification, Delaware law specifies that “in all matters other than the election of directors,” companies should count “the affirmative vote of the majority of shares of such class or series or classes or series present in person or represented by proxy at the meeting,” id. at 216(4)—the precise inverse of shareholder-proposal activists’ preferred counting rule.

The SEC staff has adopted a rule that for the very limited purpose of determining whether a proposal has met the “resubmission threshold” to qualify for inclusion on the next year’s corporate ballot—a permissive standard requiring merely a minimum 3 percent, 6 percent, or 10 percent vote, respectively, in successive years; see Amendments to Rules on Shareholder Proposals, Exchange Act Release No. 40,018; 63 Fed. Reg. 29,106, 29,108 (May 28, 1998) (codified at 17 C.F.R. pt. 240)—“[o]nly votes for and against a proposal are included in the calculation of the shareholder vote of that proposal,” ignoring abstentions. SEC Staff Legal Bulletin No. 14, F.4., July 13, 2001, https://www.sec.gov/interps/legal/cfslb14.htm (last visited Apr. 8, 2016). Because this is a staff rule not voted on by the commission, because it exists for a limited purpose (with multiple rationales, including reducing workload in processing 14a-8 no-action petitions and adopting a permissive standard for ballot inclusion), and because it contravenes clear and long-standing deference to substantive state law in the field of corporate governance, the notion that this limited SEC staff vote-counting rule should dictate counting methodology, irrespective of state law and governing corporate bylaws, is untenable.

- See Commission Guidance Regarding Disclosure Related to Climate Change, Exchange Act Release No. 34-61469, 75 Fed. Reg. 6290, 6291, 6296; John M. Broder, S.E.C. Adds Climate Risk to Disclosure List, N.Y. TIMES, Jan. 27, 2010, at B1, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/28/business/28sec.html?_r=0.

- See Alana Goodman, Memo Shows Secret Coordination Effort Against ExxonMobil by Climate Activists, Rockefeller Fund, WASH. FREE BEACON, Apr.14, 2016, http://freebeacon.com/issues/memo-shows-secret-coordination-effort-exxonmobil-climate-activists-rockefeller-fund.

- See John Schwartz, State Officials Investigated over Their Inquiry into Exxon Mobil’s Climate Change Research, N.Y. TIMES, May 19, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/science/exxon-mobil-climate-change-global-warming.html?_r=1.

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, FORBES, Apr. 24, 2013,

http://www.forbes.com/sites/feeonlyplanner/2013/04/24/socially-responsible-investing-what-you-need-to-know/#50868c655863 (“In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about”).

- Pension plans are generally bound as fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to maximize share value in their pension management. See 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008). However, those affiliated with religious organizations are exempt from this requirement. See 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- See As You Sow, Engaging Corporations. Protecting People and Planet, http://www.asyousow.org (last visited June 20, 2016).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Learn About Sustainability, https://www.epa.gov/sustainability/learn-about-sustainability#what (last visited June 21, 2016).

- See ISS, 2016 United States Summary Proxy Voting Guidelines 60 (Dec. 18, 2015), https://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/2016-us-summary-voting-guidelines-dec-2015.pdf.

- See James R. Copland et al., Proxy Monitor 2012: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism 20–23 (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Fall 2012), http://www.proxymonitor.org/pdf/pmr_04.pdf.

- See id. at 23 (citing Bryan Caplan, THE MYTH OF THE RATIONAL VOTER [2007]).

- For example, from 2006 through 2009, ISS generally recommended a vote against “proposals that call for reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by specified amounts.” See, e.g., RiskMetrics Group, 2009 U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines Summary 55 (Dec. 24, 2008), http://www.usfunds.com/media/files/pdfs/compliancepolicies/RMG2009SummaryGuidelinesUnitedStates.pdf. For the 2010 proxy season and thereafter, ISS generally recommended a vote for “shareholder proposals calling for the reduction of GHG or adoption of GHG goals in products and operations.” See, e.g., RiskMetrics Group, 2010 SRI U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines 68 (Jan. 2010), https://www.issgovernance.com/file/files/RMG_2010_SRI_US.pdf.

- Copland et al., supra note 17, at 23.

- Compare ISS, supra note 16, with ISS, 2012 SRI U.S. Proxy Voting Guidelines (Jan. 2012), https://www.issgovernance.com/file/files/2012ISSSRIUSPolicy.pdf.