PROXY MONITOR 2015

FINDING 1

2015 Proxy Season Early Report

Shareholders sponsor most resolutions at large companies since 2010; Proxy access votes split

By James R. Copland

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated executive advisory votes at America’s largest companies. This is the 33rd publication in a series of reports by Manhattan Institute Center for Legal Policy director James R. Copland, each drawing upon information in the database to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder-proposal process.[2]

|

Corporate America’s “proxy season”—the period between mid-April 15 and mid-June when most of the largest publicly traded corporations in the United States hold annual meetings to vote on company business, including resolutions introduced by shareholders[3]—is now in full swing. As of April 24, 158 of the nation’s 250 largest companies by revenues, as listed by Fortune magazine[4] and in the Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database (see box), had filed proxy documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—such that we now have a good picture of the issues facing companies in this year’s proxy season.

In 2015, companies are facing more shareholder proposals on average (1.39 per company) than they have in any year since 2010. This increase has occurred even though the most frequently introduced type of shareholder proposal—that involving a company’s political spending or lobbying—has been less commonly introduced than in 2013 or 2014. Driving the increase in shareholder-proposal activity has been a push for “proxy access”—granting shareholders the power to nominate directors to the board on the company’s proxy statement—which has been pushed aggressively in 2015 by New York City’s pension funds,[5] which are introducing 75 proxy-access proposals at companies as part of its “Boardroom Accountability Project.”[6]

Pension funds like New York’s argue that by permitting large, long-term shareholders to nominate directors without launching a full-fledged proxy fight, proxy access enables them to have a greater voice over the companies in which they own significant stakes and to improve the returns in a broadly diversified portfolio.[7] The SEC had adopted its own proxy-access rule, Rule 14a-11,[8] in 2010; the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit threw it out a year later, citing concerns that the rule might hurt ordinary investors at the expense of “investors with a special interest, such as unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value [and who] can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value.”[9] Companies and investors opposed to proxy access continue to cite concerns that overly permissive proxy-access rules could be disruptive to effective board governance.[10]

Only 44 of the Fortune 250 companies had held annual meetings by April 24—with another 17 meeting April 27 or 28 and another 11 meeting April 29 or 30. But already, a mixed verdict from shareholders on proxy-access resolutions has begun to emerge. Among the seven companies to hold votes on the topic by April 28, four companies saw shareholders give the proposal majority support, one of which (Citigroup) was with board support for the proposal. Two corporations faced competing shareholder and management proposals on the question, again with split results: at AES Corporation, a majority of shareholders supported the New York City pension funds’ proxy access proposal and rejected a competing management proposal; but at Exelon, a majority supported management’s proxy access proposal and rejected the New York City funds’ proposal.

This remainder of this finding will offer an expanded look at the early 2015 proxy season, looking first at proposal filings and then at early voting results.

Shareholder Proposal Filings

Corporate America’s “proxy season”—the period between mid-April 15 and mid-June when most of the largest publicly traded corporations in the United States hold annual meetings to vote on company business, including resolutions introduced by shareholders[11]—is now in full swing. As of April 24, 158 of the nation’s 250 largest companies by revenues, as listed by Fortune magazine[12] and in the Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database (see box), had filed proxy documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—such that we now have a good picture of the issues facing companies in this year’s proxy season.

In 2015, companies are facing more shareholder proposals on average (1.39 per company) than they have in any year since 2010. This increase has occurred even though the most frequently introduced type of shareholder proposal—that involving a company’s political spending or lobbying—has been less commonly introduced than in 2013 or 2014. Driving the increase in shareholder-proposal activity has been a push for “proxy access”—granting shareholders the power to nominate directors to the board on the company’s proxy statement—which has been pushed aggressively in 2015 by New York City’s pension funds,[13] which are introducing 75 proxy-access proposals at companies as part of its “Boardroom Accountability Project.”[14]

Pension funds like New York’s argue that by permitting large, long-term shareholders to nominate directors without launching a full-fledged proxy fight, proxy access enables them to have a greater voice over the companies in which they own significant stakes and to improve the returns in a broadly diversified portfolio.[15] The SEC had adopted its own proxy-access rule, Rule 14a-11,[16] in 2010; the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit threw it out a year later, citing concerns that the rule might hurt ordinary investors at the expense of “investors with a special interest, such as unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value [and who] can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value.”[17] Companies and investors opposed to proxy access continue to cite concerns that overly permissive proxy-access rules could be disruptive to effective board governance.[18]

Only 44 of the Fortune 250 companies had held annual meetings by April 24—with another 17 meeting April 27 or 28 and another 11 meeting April 29 or 30. But already, a mixed verdict from shareholders on proxy-access resolutions has begun to emerge. Among the seven companies to hold votes on the topic by April 28, four companies saw shareholders give the proposal majority support, one of which (Citigroup) was with board support for the proposal. Two corporations faced competing shareholder and management proposals on the question, again with split results: at AES Corporation, a majority of shareholders supported the New York City pension funds’ proxy access proposal and rejected a competing management proposal; but at Exelon, a majority supported management’s proxy access proposal and rejected the New York City funds’ proposal.

This remainder of this finding will offer an expanded look at the early 2015 proxy season, looking first at proposal filings and then at early voting results.

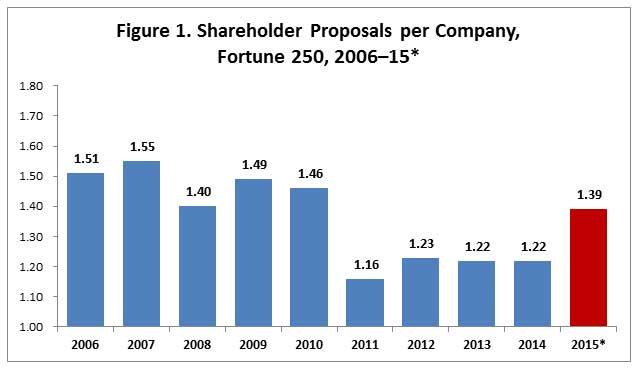

To date, the average Fortune 250 company to have filed its proxy statement in 2015 has faced 1.39 shareholder proposals—14 percent more than in 2014, and more than in any year since 2010, when Congress passed the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation that mandated that publicly traded U.S. companies hold shareholder advisory votes on an annual, biennial, or triennial basis, thus obviating shareholder proposals that sought such voting rights (see Figure 1).[19] This increase may be due, at least in part, to sampling bias, as many of the largest companies—including energy companies that tend to attract multiple environment-related shareholder proposals—have now filed proxies, and 98 companies have yet to file. Thus, the number of shareholder proposals per company for all of 2015 may be closer to the post-2010 norm once all companies are reporting.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

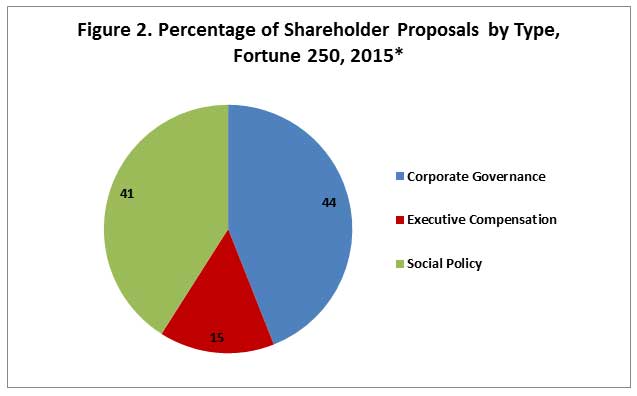

Unlike in 2014, when a plurality of shareholder proposals (47 percent) involved social or policy issues, a plurality of shareholder proposals introduced to date in 2015 (44 percent) involve corporate-governance issues like separating the board chairman and chief executive officer roles, giving shareholders proxy access to nominate directors, giving shareholders power to call special meetings or act through written consent, or modifying voting rules through which shareholders act or elect directors (see Figure 2). Social or policy issues have been the subject of 41 percent of all shareholder proposals introduced to date in 2015, and executive compensation has been the subject of 15 percent of shareholder proposals introduced.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

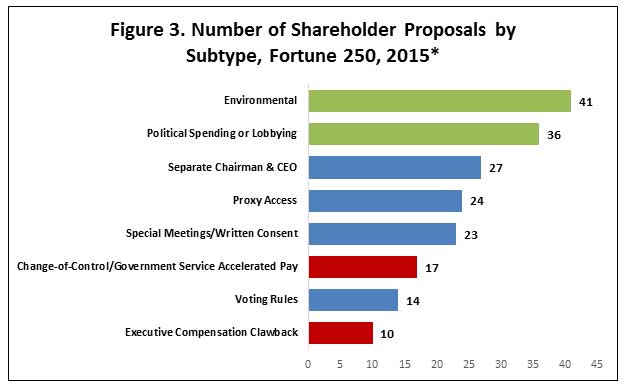

The relative decrease in the number of social- or policy-related shareholder proposals introduced, year over year, is chiefly attributable to a drop in the number of shareholder proposals involving corporate political spending or lobbying; such proposals have constituted 16 percent of all shareholder proposals in 2015, down from 22 percent last year. Although shareholder resolutions involving corporate political spending or lobbying constituted a plurality of all proposals introduced in each of the last three years, there have been five more proposals relating to environmental concerns introduced so far this year (see Figure 3)—though with 92 companies yet to file 2015 proxy statements, this ordering could shift later on.

The decline in the number of shareholder proposals involving corporate political spending or lobbying may be due to the fact that many companies have acquiesced to activists’ demands that they disclose more information about their political activities and trade association memberships.[20] In addition, certain activists concerned about corporate political spending or lobbying may have abandoned this tactic—perhaps because no such proposal has received majority shareholder support over board opposition in the ten years covered in the ProxyMonitor.org database. The New York State Common Retirement Fund, which has a partisan elected official, currently state comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, as its sole fiduciary,[21] has introduced multiple shareholder proposals related to corporate political spending in recent years but has introduced only one such proposal at a Fortune 250 company thusfar in 2015.[22]

Although social-policy-related proposals that concern the environment or political spending have been the most frequently introduced types of proposals to date in 2015, corporate-governance-related shareholder proposals have also been commonplace, as one would expect given the overall prevalence of such proposal types. Among proposals common in recent years, 2015 has seen slightly more proposals relating to separating the chairman and CEO positions and to empowering shareholders to call special meetings or act through written consent, and slightly fewer proposals seeking to modify shareholder voting rules. The big shift in corporate-governance-related shareholder proposal activity is the marked increase in the number of proposals seeking proxy access for shareholders’ director nominees; such proposals have constituted 11 percent of all proposals introduced to date in 2015, up from four percent last year. 75 percent of the proxy access proposals have been introduced by the New York City pension funds.[23]

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

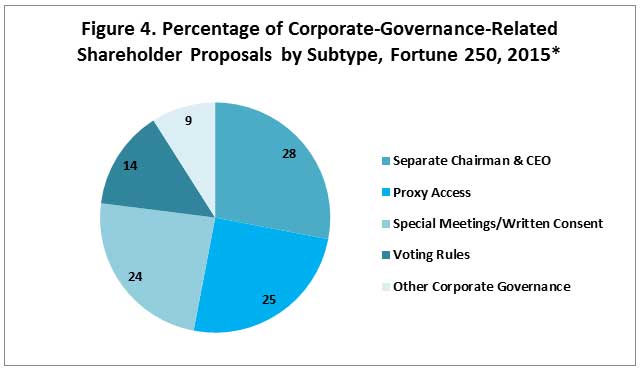

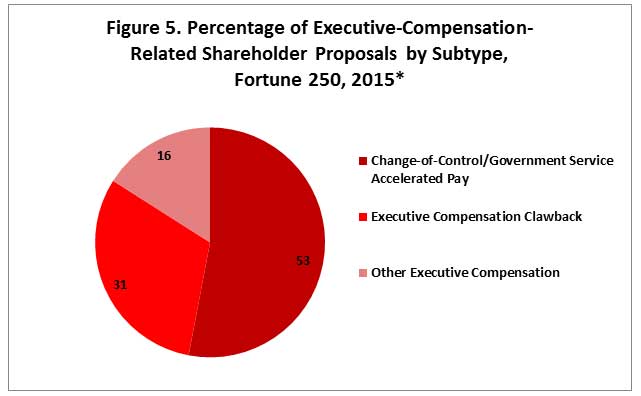

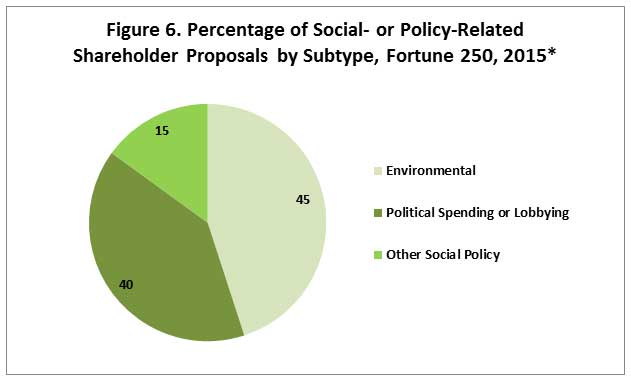

Overall, shareholder proposals have been concentrated among a few ideas. 91 percent of corporate governance proposals have involved separating the chairman and CEO, proxy access, special-meeting or written-consent rights, or voting rules (see Figure 4). 84 percent of proposals related to executive compensation have involved what critics call “golden parachutes” (the grant of accelerated compensation in the event of a change in corporate control or an executive’s departure for government service) or “clawbacks” (requiring executives to forfeit previously paid compensation in the event the company suffers from an adverse government action) (see Figure 5). 85 percent of proposals with a social or policy focus have concerned the environment or corporate political spending (see Figure 6), although there are multiple types of environment-related proposal and variations in those involving political spending or lobbying. (In keeping with recent trends, two-thirds of political-spending-related proposals have sought disclosure of corporate funds sent to organizations that lobby, which is intended to ferret out contributions to trade associations, to which companies regularly delegate lobbying authority.)

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

As has been the case in each of the last 10 years, most shareholder proposals in 2015 have been introduced by a small class of shareholders:

- “Corporate gadflies,”[24] individual investors who repeatedly file common shareholder proposals at multiple companies

- Institutional investors with a “social investing” purpose or an affiliation with a religious group, charitable mission, or public-policy organization[25]

- Pension funds, chiefly state or municipal public employee funds or private “multiemployer” funds for labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor/Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO)[26]

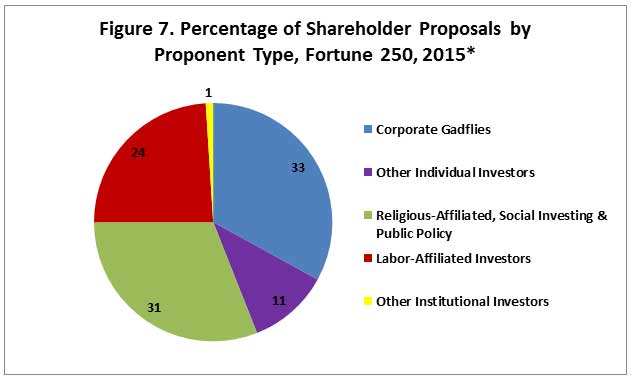

One-third of shareholder proposals introduced to date in 2015 have been sponsored by one of three individual corporate gadflies and their family members: John Chevedden, the father-son team of William and Kenneth Steiner, and the husband-wife team of James McRitchie and Myra Young (see Figure 7). 31 percent of all proposals have been sponsored by institutional investors with a social, religious, or policy purpose; a majority of these were sponsored by social-investing funds. 24 percent of all proposals were sponsored by pension funds affiliated with public or private labor unions; two-thirds of these were public-employee-fund sponsored, and 49 percent were sponsored by the pension funds for New York City employees. 11 percent of all shareholder proposals in 2015 have been sponsored by shareholders other than the three most-active gadflies, and only one percent of proposals have been sponsored by institutional investors without a labor affiliation or social, policy, or religious purpose.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

*158 of 250 companies had filed proxy documents by April 24, 2015.

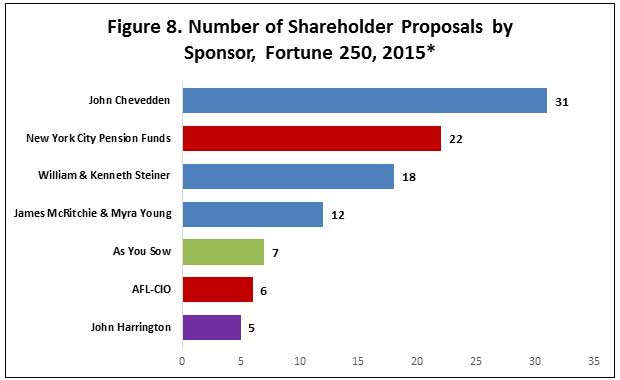

As has been the case every year since the Manhattan Institute launched the ProxyMonitor.org database in 2011, corporate gadfly John Chevedden has sponsored more shareholder proposals in 2015 than any other investor; fellow gadflies Steiner and McRitchie rank third and fourth, respectively (see Figure 8). The New York City pension funds, with their proxy-access push, are the second-most-frequent sponsors of shareholder proposals. The AFL-CIO, historically among the most active sponsors of shareholder proposals, have been—as in 2014—somewhat less active this year, although the AFL-CIO is still the sixth-most-active sponsor of shareholder proposals, with six. Although institutional investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation tend to be more dispersed in sponsoring shareholder proposals—with each investor sponsoring only a handful of proposals at large companies each year—the social-investing vehicle As You Sow has been the fifth-most-active sponsor of shareholder proposals in 2015, with seven. John Harrington, an individual investor, behaves somewhat like a corporate gadfly (he typically introduces multiple corporate-governance-related proposals) and somewhat like a social investor (he introduces multiple proposals with a social or policy purpose); in 2015, he has introduced five proposals individually at Fortune 250 companies, in addition to one proposal from his social-investing fund, Harrington Investments.[27]

Early Voting Returns

The 44 Fortune 250 companies holding annual meetings between January 1 and April 24, 2015 faced 48 shareholder proposals. Four of these received the support of a majority of shareholders: three seeking proxy access for shareholders that had held at least three percent of the company’s outstanding equity shares for at least three years, and one seeking to “declassify” the company’s board of directors (i.e., to give shareholders the opportunity to elect all directors annually, as opposed to electing one-third of the board annually to three-year terms). Overall, eight percent of shareholder proposals have received majority support in 2015—twice the percentage in 2014 but in keeping with historical norms (from 2006 through 2013, between seven and 17 percent of shareholder proposals received majority support annually). The average shareholder vote on all proposals, to date, is 27 percent—again, in line with historical averages.

Proxy Access

To date, the New York City pension funds’ 2015 push to win shareholders “proxy access” has met with some success. According to the pension funds’ spokesman, more than twelve of the 75 companies targeted by the funds’ proxy-access proposal voluntarily agreed to the proposed change.[28] Of the six such proposals opposed by the company’s board and coming to a vote by April 28 (four of which were introduced by the New York City pension funds and one each by Harrington and McRitchie), three won the support of a majority of shareholders and three did not:

- AES Corporation, April 23, 66 percent shareholder support

- American Electric Power, April 21, 67 percent

- Apple, March 10, 39 percent

- Exelon, April 28, 43 percent

- Monsanto, January 30, 53 percent

- PACCAR, April 21, 42 percent

James McRitchie’s proxy access proposal at Citigroup, meeting April 28, was supported by the company’s board of directors and received 87 percent support from shareholders. John Harrington’s proxy access proposal at Coca-Cola, meeting April 29, failed to garner a majority, with 59 percent of shareholders voting against it.

Clearly, a significant percentage of investors supports some form of proxy access: at least 39 percent of shareholders have voted for each proxy access proposal introduced at a large company in 2015. (In prior years, many proxy-access proposals received significantly less support, but most of these had lower required ownership thresholds or holding periods for nominating a director.) Conversely, a significant percentage of shareholders does not support the proxy access proposals being introduced: at least 33 percent of shareholders have opposed each proposal, except when supported by the company’s board of directors. Because the structure of each of the proposals voted on to date is essentially the same, variation in shareholder support is probably attributable to differences in ownership, differences in company performance, differences in perceived corporate governance in other areas, and differences in corporate communications on the issue to shareholders.

As discussed in the Proxy Monitor Spring 2015 Report,[29] the Securities and Exchange Commission staff initially issued a “no action” letter under section 14a-8 to Whole Foods that would have permitted the company to exclude a proxy access proposal introduced by James McRitchie because the company had introduced its own conflicting proposal seeking shareholder input on a proxy access rule with more stringent requirements for percentage ownership and holding period.[30] On January 16, 2015, SEC chairman Mary Jo White asked the agency’s staff to report back on the proper scope and application of the conflicting-proposals rule under which the proposal had been excluded, and the agency’s Division of Corporation Finance concurrently announced that it would not be issuing any further no-action letters on the appropriateness of excluding conflicting proposals from proxy ballots in the interim.[31]

The April 23 and April 28 annual meetings at AES Corp. and Exelon provided the first large-company tests of how investors would handle competing proposals. Each company faced a proxy access proposal introduced by the New York City pension funds, and the board of each company introduced its own proxy access proposal that raised the ownership threshold for nominating directors on the corporate proxy ballot to five percent (as compared to three percent on the New York City pension fund proposal), reduced the percentage of the board that could be nominated to 20 percent (as compared to 25 percent on the New York City pension fund proposal), and required that all shares be “long” rather than borrowed “short” (short-sellers were not necessarily excluded in the New York City pension fund proposal and would have interests adverse to other shareholders).

As with proxy access proposals overall, the verdict is split. At AES, 66 percent of shareholders supported the New York City pension fund proposal and only 36 percent supported the management proposal; but at Exelon, only 43 percent of shareholders supported the New York City pension fund’s proposal, while 52 percent supported the management proposal. Although the substance of the board proposals at AES and Exelon was essentially the same, the language of the Exelon board’s statement was generally more conciliatory than that of AES, and the Exelon board emphasized its other corporate-governance rules and that it had consulted with shareholders representing 39 percent of outstanding shares, with differing viewpoints on the issue, in reaching its recommendation.[32]

AES also introduced its own proposal concerning shareholder rights to call special meetings, competing with a shareholder proposal introduced by John Chevedden. 70 percent of shareholders backed the AES board’s proposal, while only 36 percent supported Chevedden’s—the opposite result from that witnessed in the company’s votes on the proxy-access competing proposals.

Executive Compensation Advisory Votes

As has been the case since shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation were first implemented in 2011, shareholders have tended to support boards’ executive compensation packages overwhelmingly. Among the 42 Fortune 250 companies holding such votes this year by April 24, none failed to receive majority shareholder support. Shareholder support averaged 92 percent, and only one company failed to win the support of at least 70 percent of shareholders for its compensation package (Qualcomm, which met March 9 and received the support of 58 percent of shareholders for its executive compensation in its advisory vote).

ENDNOTES

- Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, publicly traded companies must hold shareholder advisory votes on executive compensation annually, biennially, or triennially, at shareholders’ discretion. See Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, § 951 (2010) [hereinafter “Dodd-Frank”].

- See Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings, http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx (last visited Apr. 3, 2015).

- Shareholder resolutions can be introduced, with some regulatory constraints, by stockholders of publicly traded companies who have held shares valued at $2,000 or more for at least one year. See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007) [hereinafter “14a-8”]. The federal Securities and Exchange Commission determines the procedural appropriateness of a shareholder proposal for inclusion on a corporation’s proxy ballot, pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-291, Ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78a–78oo (2006 & Supp. II 2009)), at §§ 78m, 78n & 78u; 15 U.S.C. §§ 80a-1 to 80a-64 (2000) (pursuant to Investment Company Act of 1940, Pub. L. No. 76-768, 54 Stat. 841(1940)); but the substantive rights governing such measures and how they can force boards to act remain largely a question of state corporate law; cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”).

- See Fortune 500, available at http://fortune.com/fortune500/ (last visited Apr. 30, 2015).

- The elected New York City comptroller manages the City’s pension funds, which serve to provide retirement benefits for the City’s public employees. SeeOffice of the State Comptroller, Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller, http://www.osc.state.ny.us/pension/fiduciary.htm (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). Full fiduciary authority over the funds rests with various boards composed of political and union delegates. For example, the board of the $46 billion Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) includes the comptroller, two mayoral delegates, a delegate from the education chancellor, and three teacher delegates. See TRSNYC, Our Retirement Board, https://www.trsnyc.org/trsweb/aboutUs/ourRetirementBoard.html (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). The board of the $43 billion New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) includes the comptroller, the public advocate, a mayoral representative, each of the five New York City borough presidents, and three union delegates. See NYCERS, Board of Trustees, http://www.nycers.org/(S(azvv04mpy1qd2j5515dyny55))/about/Board.aspx (last visited Sept. 9, 2014).

- See New York City Comptroller, Boardroom Accountability Project, http://comptroller.nyc.gov/boardroom-accountability/ (last visited Apr. 14, 2015); see also Press Release, Comptroller Stringer, NYC Pensions Funds Launch National Campaign To Give Shareowners A True Voice In How Corporate Boards Are Elected: New York City Pension Funds File 75 Proxy Access Shareowner Proposals to Kick Off the Boardroom Accountability Project, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/comptroller-stringer-nyc-pension-funds-launch-national-

campaign-to-give-shareowners-a-true-voice-in-how-corporate-boards-are-elected/ (last visited Apr. 14, 2015).

- See, e.g., AES Corp., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposal no. 9 (Feb. 27, 2015) (supporting statement), http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/874761/000087476115000014/a2015proxystatement.htm#sc8ca5e5c99f0474aa727f4ad1cbb315c [hereinafter “AES Proxy Statement”].

- See 75 Fed. Reg. 56,668, 56,677 (2010).

- Bus. Roundtable v. S.E.C., 647 F.3d 1144, 1152 (D.C. Cir. 2011).

- See, e.g., AES Proxy Statement, supra note 7, at proposal no. 9 (management statement in opposition) (“the Board believes that allowing up to one quarter of the directors to be elected through a stockholder-nominated proxy access process could be highly disruptive to the operation of the Board and allow holders of a small amount of the Company’s common stock to exert undue influence on the governance of the Company”).

- Shareholder resolutions can be introduced, with some regulatory constraints, by stockholders of publicly traded companies who have held shares valued at $2,000 or more for at least one year. See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007) [hereinafter “14a-8”]. The federal Securities and Exchange Commission determines the procedural appropriateness of a shareholder proposal for inclusion on a corporation’s proxy ballot, pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-291, Ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78a–78oo (2006 & Supp. II 2009)), at §§ 78m, 78n & 78u; 15 U.S.C. §§ 80a-1 to 80a-64 (2000) (pursuant to Investment Company Act of 1940, Pub. L. No. 76-768, 54 Stat. 841(1940)); but the substantive rights governing such measures and how they can force boards to act remain largely a question of state corporate law; cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”).

- See Fortune 500, available at http://fortune.com/fortune500/ (last visited Apr. 30, 2015).

- The elected New York City comptroller manages the City’s pension funds, which serve to provide retirement benefits for the City’s public employees. See Office of the State Comptroller, Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller, http://www.osc.state.ny.us/pension/fiduciary.htm (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). Full fiduciary authority over the funds rests with various boards composed of political and union delegates. For example, the board of the $46 billion Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) includes the comptroller, two mayoral delegates, a delegate from the education chancellor, and three teacher delegates. See TRSNYC, Our Retirement Board, https://www.trsnyc.org/trsweb/aboutUs/ourRetirementBoard.html (last visited Sept. 9, 2014). The board of the $43 billion New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) includes the comptroller, the public advocate, a mayoral representative, each of the five New York City borough presidents, and three union delegates. See NYCERS, Board of Trustees, http://www.nycers.org/(S(azvv04mpy1qd2j5515dyny55))/about/Board.aspx (last visited Sept. 9, 2014).

- See New York City Comptroller, Boardroom Accountability Project, http://comptroller.nyc.gov/boardroom-accountability/ (last visited Apr. 14, 2015); see also Press Release, Comptroller Stringer, NYC Pensions Funds Launch National Campaign To Give Shareowners A True Voice In How Corporate Boards Are Elected: New York City Pension Funds File 75 Proxy Access Shareowner Proposals to Kick Off the Boardroom Accountability Project, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/comptroller-stringer-nyc-pension-funds-launch-national-

campaign-to-give-shareowners-a-true-voice-in-how-corporate-boards-are-elected/ (last visited Apr. 14, 2015).

- See, e.g., AES Corp., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposal no. 9 (Feb. 27, 2015) (supporting statement), http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/874761/000087476115000014/a2015proxystatement.htm#sc8ca5e5c99f0474aa727f4ad1cbb315c [hereinafter “AES Proxy Statement”].

- See 75 Fed. Reg. 56,668, 56,677 (2010).

- Bus. Roundtable v. S.E.C., 647 F.3d 1144, 1152 (D.C. Cir. 2011).

- See, e.g., AES Proxy Statement, supra note 7, at proposal no. 9 (management statement in opposition) (“the Board believes that allowing up to one quarter of the directors to be elected through a stockholder-nominated proxy access process could be highly disruptive to the operation of the Board and allow holders of a small amount of the Company’s common stock to exert undue influence on the governance of the Company”).

- See Dodd-Frank, supra note 1, at § 951.

- See, e.g., NYC Comptroller, 2014 Shareowner Initiatives of the New York City Pension Funds, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/shareowner-initiatives/ (observing that Regions Financial “agreed to disclose its direct and indirect political spending, having received the NYC Funds’ disclosure proposal every year since 2005”) (last visited May 1, 2015).

- See Office of the State Comptroller, Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller, http://www.osc.state.ny.us/pension/fiduciary.htm (last visited Sept. 9, 2014).

- Fourteen of the 20 shareholder proposals introduced by the New York State Common Retirement Fund in 2014 involved corporate political spending or lobbying, four involved environmental issues, one involved employment rights, and one involved executive compensation.

- Three proposals have been introduced by John Harrington and his social-investing fund, two have been introduced by corporate gadfly James McRitchie, and one has been introduced by the pension fund for the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS).

- “Corporate gadflies,” as commonly used in Charles M. Yablon, Overcompensating: The Corporate Lawyer and Executive Pay, 92 COLUM. L. REV. 1867, 1895 (1992); and Jessica Holzer, Firms Try New Tack Against Gadflies, WALL ST. J. (June 6, 2011), http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304906004576367133865305262.html.

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, FORBES (Apr. 24, 2013), http://www.forbes.com/sites/feeonlyplanner/2013/04/24/socially-responsible-investing-what-you-need-to-know (“In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about.”). Note that Although pension plans are generally bound as fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to maximize share value in their pension management, 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008), those affiliated with religious organizations are exempt from this requirement, 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- Under the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act, Pub. L. No. 93-406, § 514, 88 Stat. 829, 897 (1974), codified at 29 U.S.C. §§ 1001–1461 (2006), fiduciary duties governing employee benefit plan investment portfolios require that “in voting proxies . . . the responsible fiduciary shall consider only those factors that relate to the economic value of the plan’s investment and shall not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income to unrelated objectives,” 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008); but such fiduciary duties do not extend to state or municipal plans, see 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- Harrington Investments describes itself as “a leader in Socially Responsible Investing and Shareholder Advocacy since 1982 ... dedicated to managing portfolios for individuals, foundations, non-profits, and family trusts to maximize financial, social and environmental performance.” Harrington Investments, Inc., About Us, http://harringtoninvestments.com/about-us (last visited Aug. 1, 2014).

- See Sally Goldenberg, Stringer “Boardroom” Movement Finds Some Takers, CAPITAL NY (Apr. 30, 2015), http://www.capitalnewyork.com/article/city-hall/2015/04/8567048/stringer-boardroom-movement-finds-some-takers.

- See James R. Copland, Proxy Monitor Spring 2015: Recent Legal and Regulatory Changes Create Uncertain Landscape for 2015 Proxy Season: Proxy Access on the Agenda (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Spring 2015), http://www.proxymonitor.org/Forms/pmr_10.aspx.

- See No-Action Letter Re: Whole Foods, Inc., SEC, http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8/2014/jamesmcritchie120114.pdf (last visited Apr. 15, 2015).

- See Public Statement, Statement from Chair White Directing Staff to Review Commission Rule for Excluding Conflicting Proxy Proposals, SEC (Jan. 16, 2015), http://www.sec.gov/news/statement/statement-on-conflicting-proxy-proposals.html#.VST9b_nF_Wt; see also 14a-8, supra note 3, at subsection (i)(9) (“If the proposal directly conflicts with one of the company's own proposals to be submitted to shareholders at the same meeting”).

- Compare AES Proxy Statement, supra note 7, at proposals no. 7, 9 with Exelon Corp., Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, proposals no. 5, 6 (Mar. 19, 2015), http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1109357/000119312515098237/d876808ddef14a.htm#rom876808_18.