PROXY MONITOR 2014

FINDING 4

Special Report: Shareholder Activism by Socially Responsible Investors

Social-investing funds assume leading role in policy-oriented shareholder-proposal activism; focus on environmental issues and corporate political spending.

By James R. Copland

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated[1] executive-compensation advisory votes at America’s largest companies. This is the 27th in a series of findings and reports, drawing upon information in the database, to examine shareholder activism in which investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder voting process.[2]

|

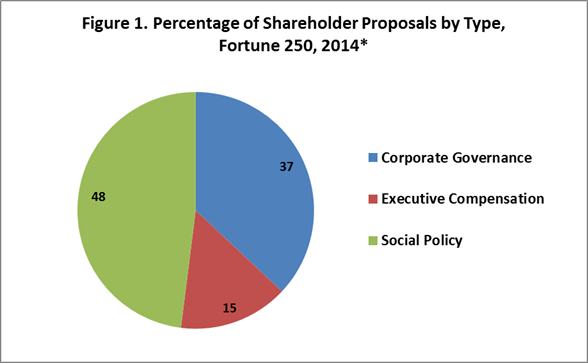

One of the major story lines this proxy season—the period between mid-April and the end of June, when most of America’s largest corporations hold annual meetings—is the increased role that social and policy issues have played among shareholder proposals (which can be introduced for consideration by stockholders who have held $2,000 in a publicly traded company’s equity for at least one year).[3] Of the shareholder proposals introduced at the 219 Fortune 250 companies to have held annual meetings to date,[4] 48 percent involved social or policy concerns (Figure 1). As contrasted with proposals related to the rules of corporate governance, shareholder proposals with a “socially responsible” investing purpose—also called “sustainable,” “socially conscious,” “mission,” “green,” or “ethical” investing—have only an attenuated connection, if any, to the company’s financial interests.[5] The percentage of shareholder proposals relating to social or policy issues in 2014 is 17 percent higher than in 2013 and nearly 30 percent above the 2006–13 average.

*Reports filed, to date, by 219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

Although shareholder proposals relating to social or policy issues are introduced by individual stockholders and labor-affiliated investors (particularly state and municipal pension funds),[6] they are most commonly sponsored by “socially responsible” investment funds and investment vehicles affiliated with public-policy organizations or religious institutions. In 2014, social-investing funds have moved to the forefront, sponsoring a majority of all proposals introduced by this investor class. Consistent with earlier years, however, most shareholders have rejected the social and policy proposals being introduced: not a single 2014 proposal sponsored by this investor class received majority shareholder support over board opposition.

This finding focuses in greater detail on shareholder-proposal activity from institutional investors with a religious, social, or public-policy bent. Part I examines the role played by such investors in general and over time, as well as the various leading institutions working to fulfill a social-investing mission. Part II looks at the types of shareholder proposals backed by social-oriented investors. Part III looks at shareholder votes on these investors’ proposals, with a particular focus on proposals repeatedly filed at the same company—and with only limited shareholder support.

I. Social-Oriented Investors and Shareholder Activism

Background

Under guidelines promulgated by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), publicly traded companies generally are not required to submit to a vote on shareholder proposals relating to “ordinary business practices.”[7] A long-standing exception to this rule requires companies to let shareholders consider proposals involving “political and moral predilections.”[8] Many institutional investors with an express orientation toward “socially responsible” investing,[9] as well as various retirement and investment vehicles associated with religious or public-policy organizations,[10] have availed themselves of this exception to submit shareholder proposals designed to influence companies to alter their behavior in keeping with those organizations’ goals.

Shareholder-Proposal Activity

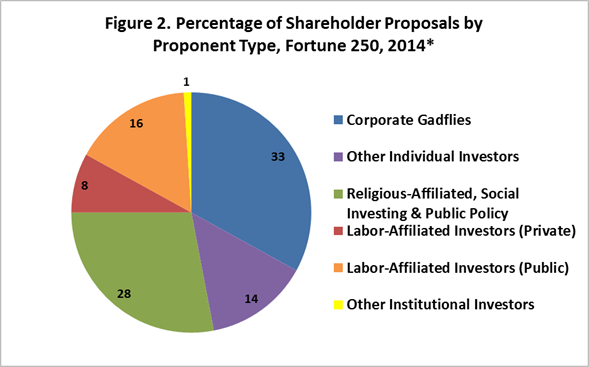

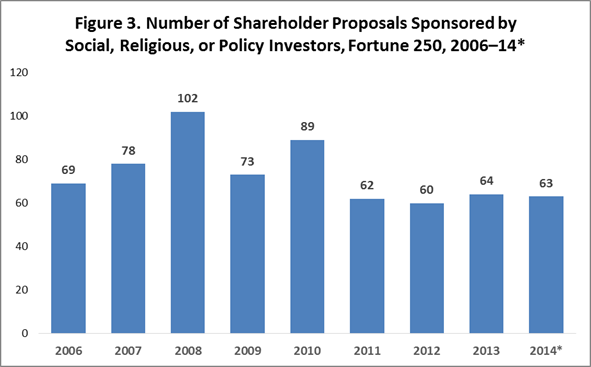

In 2014, investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation have sponsored 28 percent of all shareholder proposals listed on Fortune 250 companies’ proxy ballots (Figure 2), up from 25 percent in 2013. With 219 of 250 companies reporting, social-, religious-, and policy-oriented investors have sponsored 63 shareholder proposals—on track to be the highest level of shareholder-proposal activity among this class of investors since 2010 (Figure 3).

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

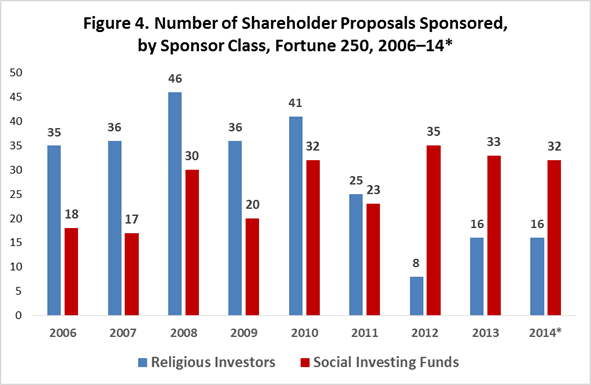

Although the number of shareholder proposals sponsored by investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation has remained relatively consistent in recent years—from 2011 through 2013, this class of investors sponsored between 60 and 64 proposals at Fortune 250 companies—there has been a noticeable shift in which types of investors have been most active, in comparison with earlier periods. From 2006 through 2010, a plurality of all proposals sponsored by social-, religious-, or policy-oriented investors were introduced by religious-affiliated groups, principally Catholic orders of nuns and monks but also investment vehicles associated with the Unitarians, the Episcopals, and the Presbyterian Church (USA). Over this period, investors with a religious affiliation sponsored between 35 and 46 shareholder proposals annually (Figure 4). That number fell to 25 in 2011, and then plummeted to 8 in 2012, before rebounding slightly (to 16) in each of the last two years. This decline was largely attributable to a significant pullback in shareholder-proposal activity from Catholic-affiliated religious orders, following a Vatican reprimand of U.S. nuns over perceived political radicalism.[11]

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

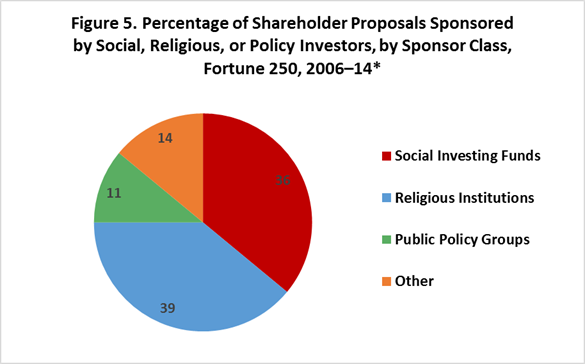

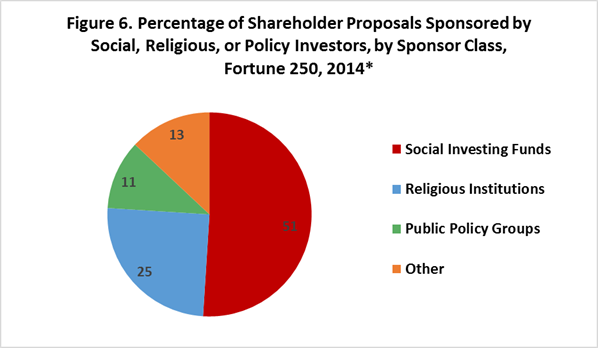

As shareholder proposals sponsored by religious-affiliated investors have waned, social-investing funds—openly marketed toward environmental, social, or “good governance” goals (“ESG”)[12]—have become more active in shareholder-proposal activism. From 2006 through 2011, the number of shareholder proposals sponsored by social-investing funds at Fortune 250 companies varied from 17 to 32, with ups and downs correlating roughly with religious-oriented investing funds.[13] In no year over this period was the number of shareholder proposals sponsored by social-investing funds greater than the number sponsored by religious-oriented investors. From 2012 through 2014, as shareholder-proposal activity among religious investors fell markedly, it increased significantly among social-investing funds, which sponsored 35 and 33 proposals, respectively, in 2012 and 2013, and 32 to date in 2014. Over the entire 2006–14 period, religious-oriented investors sponsored 39 percent of all shareholder proposals introduced by ESG-focused investors—and social-investing funds, 36 percent (Figure 5). In 2014, 51 percent of these proposals were sponsored by social-investing funds and only 25 percent by religious institutions (Figure 6).

*In 2014, 219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

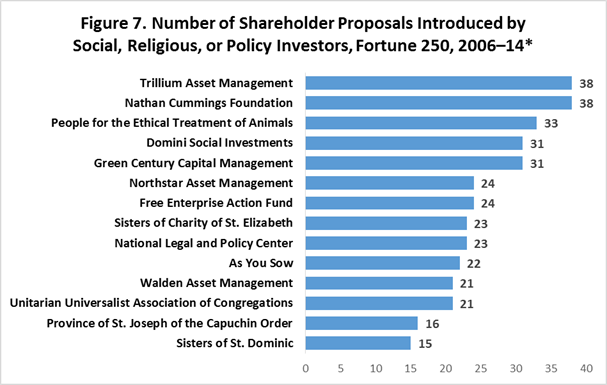

Although a small subset of investors dominate shareholder-proposal activism by labor-affiliated investors and corporate gadflies, such activism is spread among social-oriented investors more broadly. Three labor-affiliated investors (AFL-CIO, AFSCME, and New York City pension funds) and three corporate gadflies (John Chevedden, Kenneth and William Steiner, and Evelyn Davis) each sponsored at least 100 shareholder proposals from 2006 through 2014. The two most active social-oriented investors, Trillium Asset Management[14] and the Nathan Cummings Foundation,[15] each sponsored just 38 (Figure 7). Twelve others, however, each sponsored between 15 and 33 shareholder proposals: the social-investing funds Domini Social Investments, Green Century Capital Management, Northstar Asset Management, As You Sow, and Walden Asset Management; the policy-oriented People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), Free Enterprise Action Fund, and National Legal and Policy Center; and the religious entities Sisters of Charity of St. Elizabeth, Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations, Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order, and Sisters of St. Dominic. Four additional social-investing funds (Boston Common Asset Management, Needmor Fund, Harrington Investments, and Calvert Asset Management) and six additional religious institutions (Mercy Investment Program, Sisters of Charity of the BVM, Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, Presbyterian Church [USA], Sisters of St. Francis, and Christian Brothers Investment Services) each sponsored between 10 and 14 shareholder proposals over this period.

*In 2014, 219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

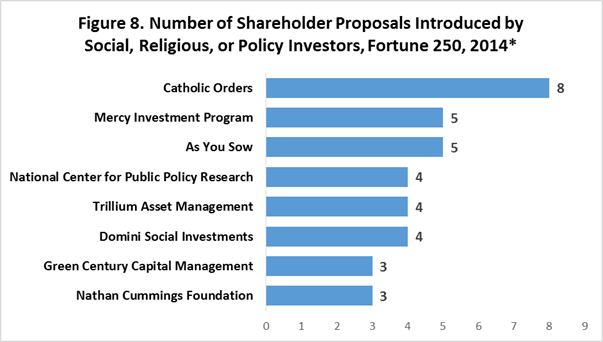

In 2014, although religious investors were overall less active than in the 2006–11 period, Catholic orders of monks and nuns, in aggregate, sponsored eight shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies; Mercy Investment Program sponsored five (Figure 8). Four social-investing funds—As You Sow, Trillium Asset Management, Domini Social Investments, and Green Century Capital Management—each sponsored between three and five shareholder proposals (a diverse group of other social-investing funds sponsored 16 shareholder proposals). The right-leaning public-policy group National Center for Public Policy Research and the left-leaning charitable foundation Nathan Cummings Foundation sponsored four and three shareholder proposals, respectively.

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

II. Subject Matter of Social Investors’ Shareholder Proposals

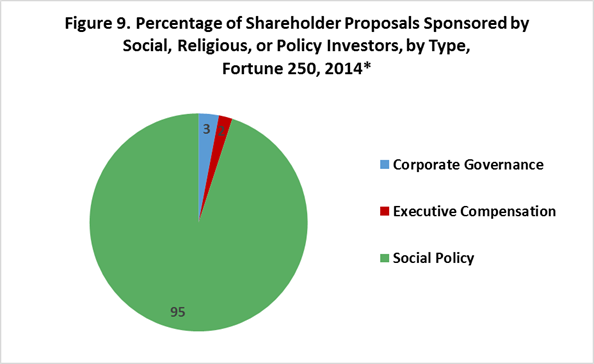

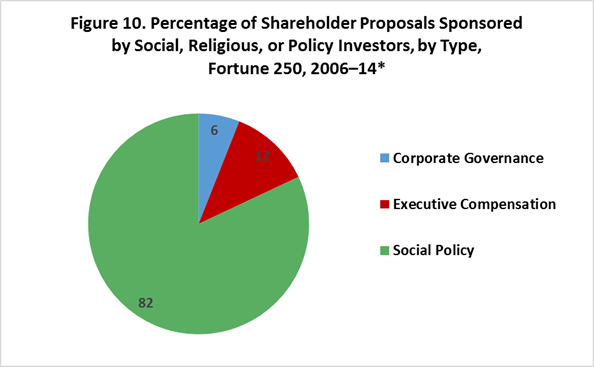

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the vast majority (95 percent) of shareholder proposals sponsored by investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation in 2014 did indeed have a social or policy orientation (Figure 9). Over the full period from 2006 through 2014, 82 percent of these investors’ shareholder proposals dealt with social or policy issues (Figure 10). Among the 12 percent of proposals across the broader period dealing with executive compensation, two-thirds called for executive-compensation advisory votes—“say on pay” rules—before the SEC mandated such votes for all companies in the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act. Also, in earlier years but not in 2014, several religious-organization investors sponsored corporate-governance-related proposals seeking to separate the company’s chairman and chief executive officer positions; the charitable Nathan Cummings Foundation introduced four proposals to “declassify” corporate boards and elect all directors annually.

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*In 2014, 219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

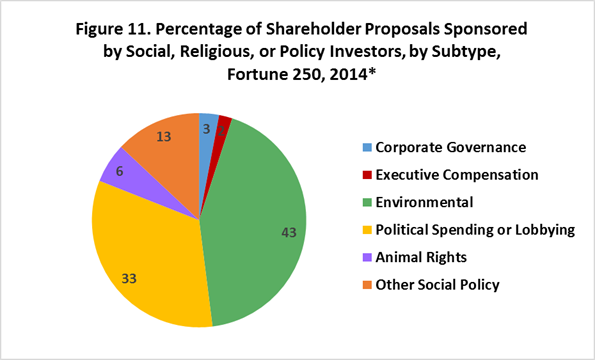

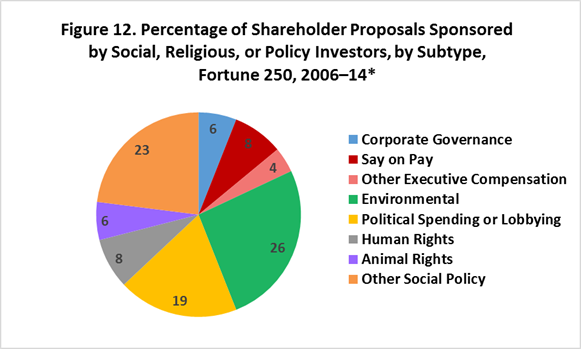

Among the social and policy proposals that dominated social investors’ 2014 shareholder-proposal activism, 43 percent involved environmental concerns and 33 percent involved corporate political spending or lobbying (Figure 11)—a higher share than in the broader 2006–14 period, when such proposals constituted 26 percent and 19 percent, respectively, of social-investor-sponsored shareholder proposals (Figure 12). In both 2014 and the broader period, 6 percent of these investors’ shareholder proposals involved animal rights; human-rights-related proposals constituted 8 percent of social investors’ shareholder proposals in the 2006–14 period (though only two such proposals were introduced in 2014).

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

III. Voting Results

In 2014, only one shareholder proposal sponsored by social, religious, or policy investors received majority shareholder support: a proposal for a “laudatory resolution in support of animal welfare” introduced by the Humane Society at Kraft Foods, which received the support of 76 percent of shareholders after the company’s board of directors endorsed the proposal. Two other proposals calling for increased disclosure of political spending at Duke Energy and Emerson Electric received between 40 and 43 percent of the shareholder vote.[16]

The 2014 voting results for social investors’ shareholder proposals are broadly consistent with those observed over the broader 2006–14 period. Of the 539 shareholder proposals with a social or policy focus sponsored by this investor class from 2006 through 2014, only two received the support of a majority of shareholders: the 2014 Kraft Foods animal-welfare proposal and a 2006 proposal introduced by Green Century Capital Management at Amgen calling for increased disclosure of the company’s political spending (which received the support of 67 percent of shareholders after the board of directors supported the proposal). Put differently, all 537 shareholder proposals with a social or policy orientation that social-investing-oriented investors sponsored at Fortune 250 companies from 2006 through 2014 failed to attract the support of a majority of shareholders. (Twelve other shareholder proposals introduced by this class of investor also received majority support: the four board-declassification proposals introduced by the Nathan Cummings Foundation; six of 51 say-on-pay proposals; and a pair of 2008 proposals introduced by the Children’s Investment Fund at CSX, seeking to overturn that company’s bylaw amendments and give shareholders additional powers to call special meetings.)

Notably, in many instances, social-oriented investors repeatedly filed identical (or substantially similar) proposals at the same company in successive years—notwithstanding the fact that these proposals repeatedly failed to gain majority shareholder support. In 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009, respectively, PETA sponsored animal-welfare proposals at YUM! Brands: in each instance, between 92 and 97 percent of shareholders rejected such proposals. In 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013, respectively, the Sisters of St. Dominic supported shareholder proposals at Exxon Mobil calling on the company to produce a report on its greenhouse-gas emissions: in each instance, between 68 percent and 74 percent of shareholders rejected such proposals. In 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013, respectively, various social- and religious-oriented investors (Green Century Capital Management, Brethren Brotherhood Trust, Pax World Mutual Funds, and Clean Yield Asset Management) sponsored shareholder proposals calling on CVS Caremark to increase its disclosure of political spending: in each instance, between 65 and 72 percent of shareholders rejected such proposals.[17]

Conclusion

Shareholder-proposal activism by investors with a social, political, or religious orientation has been unsuccessful in winning majority shareholder support for such investors’ social and religious causes. It has persisted, however, because risk-averse corporate managements, sensitive to brand perception, have—despite investor opposition—reacted to such activism by changing practices;[18] and because shareholder-proposal activism provides a platform for media and other public attention for social and policy causes.[19]

The D.C. Circuit’s 1970 decision requiring companies to include shareholder proposals involving a moral or political concern on their proxy statements means that such shareholder-proposal activism is here to stay. Nevertheless, it is questionable whether allowing substantially similar proposals to be submitted to a shareholder vote at the same company, year after year—and in the face of consistent opposition from a majority of shareholders—makes sense from a corporate-governance perspective. In essence, the average diversified investor is paying a “shareholder-proposal tax” to social-oriented investors. The SEC is currently facing a rulemaking petition seeking to increase the threshold requirements for resubmitting substantially similar shareholder proposals,[20] which it should strongly consider.[21]

ENDNOTES

-

Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010).

- See Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings, http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx (last visited June 5, 2014).

- See 17 C.F.R. § 240.14a-8 (2007).

- Twelve companies, whose annual meeting results appear in the Proxy Monitor database, were not in the Fortune 250 list for 2013 and therefore are excluded from this analysis: Aon, Ashland, Coca-Cola Enterprises, Devon Energy, Eaton, ITT, KBR, Motorola, Oshkosh, Public Service Enterprise Group, Sempra Energy, and the Williams Companies.

- See Michael Chamberlain, Socially Responsible Investing: What You Need to Know, Forbes, Apr. 24, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/feeonlyplanner/2013/04/24/socially-responsible-investing-what-you-need-to-know (“In general, socially responsible investors are looking to promote concepts and ideals that they feel strongly about”).

- See James R. Copland, Special Report: Labor-Affiliated Shareholder Activism (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Finding 3, 2014).

- The SEC determines the procedural appropriateness of a shareholder proposal for inclusion on a corporation’s proxy ballot, pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Pub. L. No. 73-291, Ch. 404, 48 Stat. 881 (1934) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78a–78oo [2006 & Supp. II 2009]), at §§ 78m, 78n & 78u; 15 U.S.C. §§ 80a-1 to 80a-64 (2000) (pursuant to Investment Company Act of 1940, Pub. L. No. 76-768, 54 Stat. 841 [1940]); but the substantive rights governing such measures and how they can force boards to act remain largely a question of state corporate law; cf. Del. Code Ann., tit. 8, § 211(b) (2009) (noting that, in addition to the election of directors, “any other proper business may be transacted at the annual meeting”).

- See Med. Comm. for Human Rights v. SEC, 432 F.2d 659, 682 (D.C. Cir. 1970) (remanding to the SEC for reconsideration a no-action letter that would have permitted Dow Chemical to exclude from its proxy statement a shareholder proposal involving its sale of napalm), aff’d 404 U.S. 403 (1972) (affirmed for mootness, after Dow had included the resolution on its proxy).

- See Chamberlain, supra note 5 (defining “socially responsible investing”).

- Although pension plans are generally bound as fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) to maximize share value in their pension management, 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008), those affiliated with religious organizations are exempt from this requirement, 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- See Wyatt Andrews, Vatican Reprimands U.S. Nuns over “Radical Feminist Themes,” CBS News (Apr. 12, 2012), http://www.cbsnews.com/news/vatican-reprimands-us-nuns-over-radical-feminist-themes.

- See Chamberlain, supra note 5 (“Investment in companies and governments that the investor believes best hold to values of importance to the investor. These include the environment, consumer protection, religious beliefs, employees’ rights as well as human rights, among others. These areas of concern can be summarized as ‘Environmental, Social and Governance’ ... referred to as ESG investing. In addition, SRI includes shareholder advocacy and community investing”).

- That social-investing funds’ shareholder-proposal activity tended to rise and fall over this period in parallel to religious-investing funds’ activity may suggest coordination among these investor classes.

- Trillium Asset Management is “the oldest independent investment advisor devoted exclusively to sustainable and responsible investing,” and the fund actively “leverages the power of stock ownership to promote social and environmental change,” Trillium Asset Management, About Us, http://www.trilliuminvest.com/socially-responsible-investment-company (last visited July 18, 2014).

- The Nathan Cummings Foundation is a charitable foundation “committed to democratic values and social justice” that “seek[s] to build a socially and economically just society that values nature and protects the ecological balance for future generations; promotes humane health care; and fosters arts and culture that enriches communities.” Nathan Cummings Foundation, About the Foundation, http://www.nathancummings.org/about-the-foundation (last visited July 18, 2014).

- The 42.5 percent vote support for increased political spending disclosure at Duke Energy may flow from controversy stemming from a well-publicized coal-ash spill that led large public-employee pension funds, including the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) and the New York City pension funds, to challenge the company’s director nominees. See Barry B. Burr, CalPERS, NYC Retirement Systems Oppose Duke Energy Directors in Coal-Ash Spill Aftermath, Pensions & Investments (Apr. 15. 2014), http://www.pionline.com/article/20140415/ONLINE/140419927/calpers-nyc-retirement-systems-oppose-duke-energy-directors-in-coal-ash-spill-aftermath. Duke Energy is the former employer of, and closely tied to, North Carolina Republican governor Pat McCrory, whose budget-cutting policies have spurred much controversy among the state’s public employees. WCTI Staff, Teachers Protest State Budget During Gov. McCrory’s Visit, ABC WCTI12 (Aug. 6, 2013), http://www.wcti12.com/news/teachers-protest-state-budget-during-gov-mccrorys-visit/21496436.

- Although a majority of shareholders have consistently opposed proposals like those involving greenhouse-gas emissions and political-spending disclosure, the voting totals suggest more shareholder support for these proposals than likely exists, were shareholders actively to consider these proposals. These proposals are typically supported by Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), the leading proxy-advisory firm, to which many institutional investors—especially smaller funds—regularly outsource their shareholder-proposal voting. An earlier Proxy Monitor analysis suggested that, controlling for other factors, ISS acts equivalent to a 15 percent owner of the total stock market in shareholder-proposal voting. See James R. Copland et al., Proxy Monitor 2012: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism (Manhattan Inst. for Pol’y Res., Fall 2012), http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/pmr_04.aspx. Recent SEC rulemaking governing proxy-advisory firms places new obligations on ISS and other proxy advisors and may affect these firms’ influence going forward. SEC, Proxy Voting: Proxy Voting Responsibilities of Investment Advisers and Availability of Exemptions from the Proxy Rules for Proxy Advisory Firms, Staff Legal Bulletin No. 20 (IM/CF), http://www.sec.gov/interps/legal/cfslb20.htm (last visited July 18, 2014).

- See, e.g., Press Release, Kraft Foods Switches One Million Eggs to Cage-Free, Humane Society (Nov. 11, 2010), http://www.humanesociety.org/news/press_releases/2010/11/kraft_111110.html; see also Press Release, Trillium Successfully Withdraws Lobbying Disclosure Resolution at Amgen, Trillium Asset Management (Dec. 9, 2013), http://www.trilliuminvest.com/tag/amgen.

- See Emily Chasan, More Companies Bow to Investors with a Social Cause:Shareholders Drive Changes in Policies Ranging from Rain Forests to Human Rights, Wall St. J. (Mar. 31, 2014), http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304157204579471383739569084.

- SEC, Petition for Rulemaking Regarding Resubmission of Shareholder Proposals Failing to Elicit Meaningful Shareholder Support (2014), http://www.sec.gov/rules/petitions/2014/petn4-675.pdf.

- The SEC currently requires companies to permit shareholders to resubmit substantially similar shareholder proposals on proxy ballots if such proposals have received a minimum 3 percent, 6 percent, or 10 percent vote, excluding abstentions, in the first, second, and third years of such proposals’ introduction; see Amendments to Rules on Shareholder Proposals, Exchange Act Release No. 40,018; 63 Fed. Reg. 29,106, 29,108 (May 28, 1998) (codified at 17 C.F.R. pt. 240), http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/34-40018.htm#foot9 (“If the proposal deals with substantially the same subject matter as another proposal or proposals that has or have been previously included in the company’s proxy materials within the preceding 5 calendar years, a company may exclude it from its proxy materials for any meeting held within 3 calendar years of the last time it was included if the proposal received: (i) Less than 3% of the vote if proposed once within the preceding 5 calendar years; (ii) Less than 6% of the vote on its last submission to shareholders if proposed twice previously within the preceding 5 calendar years; or (iii) Less than 10% of the vote on its last submission to shareholders if proposed three times or more previously within the preceding 5 calendar years”). This standard seems very small, particularly in light of the large influence that ISS and other proxy-advisory firms have over shareholder voting. Given that our research suggests that ISS support, ceteris paribus, translates into 15 percent voting support for any shareholder proposal (see Copland et al., supra note 17), the SEC’s current low resubmission thresholds ensure that winning ISS support for any shareholder proposal permits its resubmission, ad infinitum.