PROXY MONITOR 2014

FINDING 3

Special Report: Labor-Affiliated Shareholder Activism

Pension funds affiliated with multiemployer private funds scale back shareholder activism in 2014; public-employee funds pursue political

agenda

ABOUT PROXY MONITOR

The Manhattan Institute’s ProxyMonitor.org database, launched in 2011, is the first publicly available database cataloging shareholder

proposals and Dodd-Frank-mandated[1] executive-compensation advisory votes at America’s largest companies. This is

the 26th in a series of findings and reports drawing upon information in the database, each of which examines shareholder activism in which

investors attempt to influence corporate management through the shareholder voting process.[2]

|

By the end of June, most of America’s largest publicly traded corporations—including 219 of the 250 largest companies by revenue—had held their annual meetings to vote on company business, including shareholder proposals.[3] As noted in our mid-season report on the 2014 proxy season, the number of shareholder proposals introduced this year was in line with recent trends, but shareholders have been less likely to support such proposals than in any year dating back to 2006 (the earliest year in the Proxy Monitor database). This finding focuses on shareholder-proposal activity from labor-affiliated pension funds,[4] one of the three investor groupings responsible for the vast majority of shareholder-proposal activity (alongside investors with a social, religious, or policy orientation and individual “corporate gadflies,” who repeatedly file similar proposals at multiple companies).

As noted in the mid-season report, the percentage of shareholder-proposal activity sponsored by labor-affiliated funds has dropped significantly this year: only 24 percent of shareholder proposals to date in 2014 were principally backed by a labor fund, in contrast to 35 percent in 2013. This follow-up analysis shows, however, that the drop in labor-fund activity stems mostly from a decline in proposal sponsorship among “multiemployer” pension funds, such as the United Steelworkers, the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), and the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). Proposal sponsorship by specific state and municipal-employee pension plans—led by funds managing retirement benefits for public workers in New York City and State—has remained robust.

This finding explores these trends in more detail. Part I examines the role played by labor-affiliated pension funds in the shareholder-proposal process in each of the last two years, focusing on the distinction between public- and private-oriented labor-affiliated funds. Part II looks at the type of shareholder proposals that labor-affiliated funds have backed. Part III focuses on labor-backed shareholder proposals related to corporate political spending and lobbying, which have constituted a majority of such proposals introduced by labor-affiliated shareholder proposals in 2014.

I. Labor-Affiliated Sponsors of Shareholder Proposals

Background

Pension funds managing retirement assets for employees are among the largest investors in the marketplace and have historically been among the most active sponsors of shareholder proposals at publicly traded corporations. Such funds can be organized for the employees of specific companies or as multiemployer plans affiliated with labor unions that span multiple companies across one or more industries, such as the United Steelworkers, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO, or AFSCME.[4] Other such funds exist as creatures of states and municipalities on behalf of public-sector workers.

In recent years, the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Labor and the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit have each separately questioned the degree to which labor pension funds’ activities in the proxy process are wholly related to share value.[6] (Company and multiemployer funds are generally bound as fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act [ERISA] to maximize share value in their pension management,[7] but state and municipal plans, as well as those affiliated with religious organizations, are exempt from ERISA.)[8] In addition, the Public Benefit Guaranty Corporation(PBGC), which guarantees single-employer and multiemployer pension plans through separate insurance systems, has observed that multiemployer pension plans are woefully underfunded, such that, at current premium levels and projected failure rates, the corporation’s reserves are likely to be depleted by 2022, with a 90 percent likelihood of such depletion by 2025.[9]

Shareholder-Proposal Activity

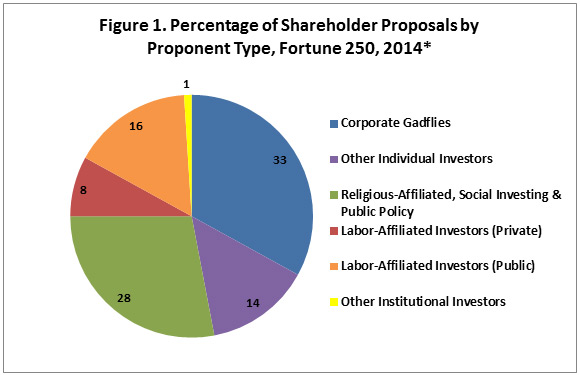

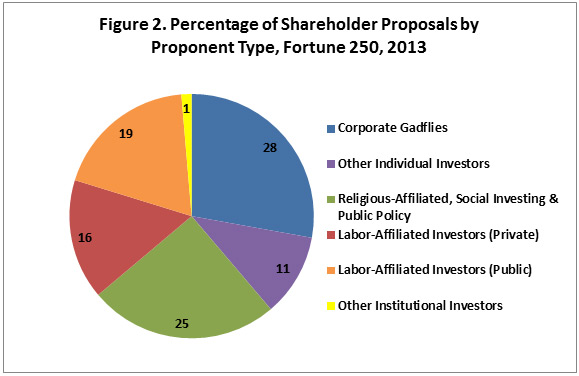

In 2014, the percentage of shareholder proposals sponsored by labor-affiliated pension funds has dropped. This drop has largely stemmed from a decline in shareholder activism by private, multiemployer plans: the percentage of shareholder proposals sponsored by pension funds affiliated with companies or private pension plans has fallen from 16 percent of all proposals in 2013 to 8 percent in 2014 (Figures 1 and 2), which may or may not be attributable to such plans’ financial struggles and a reassessment of how shareholder activism fits into their investment strategy. The percentage of shareholder proposals sponsored by pension funds affiliated with public employees—including state- and municipal-employee pension funds and the fund for AFSCME—dropped more modestly year over year, from 19 percent to 16 percent.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*Reports filed, to date, by 219 of 250 companies

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

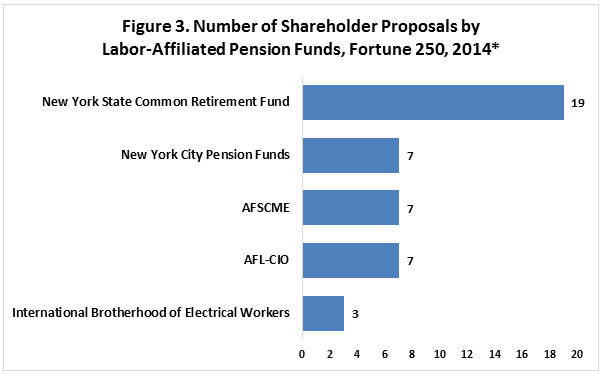

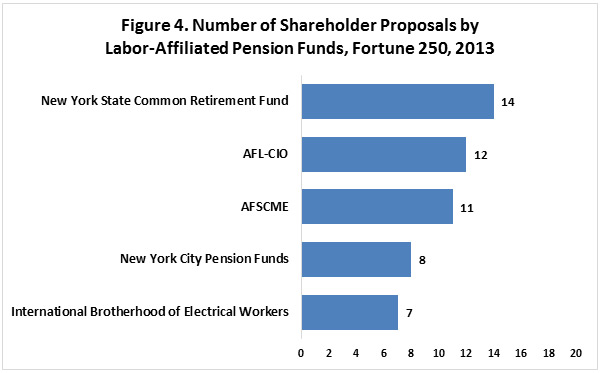

The decline in shareholder activism among pension funds affiliated with public employees is explained by a modest drop in such activism by AFSCME, rather than by a drop in public-employee pensions organized directly under the auspices of states and municipalities. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, AFSCME has sponsored seven shareholder proposals to date in 2014, down from 11 in 2013. (In keeping with the overall drop in multiemployer plan activism in 2014, the two most active pension funds affiliated with private employers, the AFL-CIO and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, have also been less active than in 2013.)

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

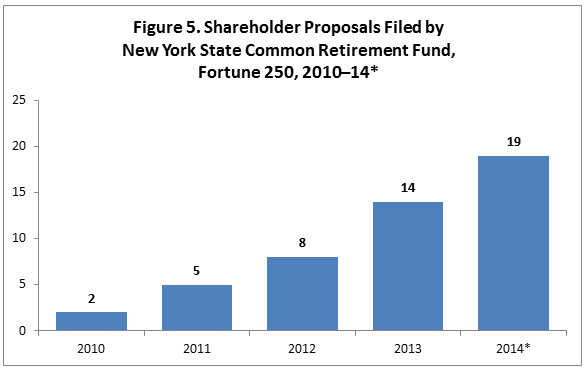

As in 2013, the most active sponsor of shareholder proposals this year has been the New York State Common Retirement Fund, which holds assets in trust for the New York State & Local Retirement System (NYSLRS).[10] This fund’s sole trustee is the state’s publicly elected comptroller,[11] currently Democrat Thomas P. DiNapoli, a politician who had no previous investment-management experience when initially selected for the post by the state legislature in 2007.[12] The New York State fund introduced no shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies between 2006 and 2009, introduced two in 2010, and has steadily increased its shareholder activism in each subsequent year (Figure 5). The 19 proposals introduced by the New York State Common Retirement Fund in 2014 were more than the number sponsored by any other shareholder proponent—save the two most active “corporate gadflies,” John Chevedden and the father-son tandem of William and Kenneth Steiner.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Behind the New York State fund, the pension funds for New York City employees, the AFL-CIO, and AFSCME have each introduced seven shareholder proposals at Fortune 250 companies in 2014. The New York City funds have a history of shareholder activism, particularly that with a social bent, dating long before the 2013 election of City Comptroller Scott Stringer;[13] indeed, the New York City pensions and comptroller’s office have been the most active sponsors of shareholder proposals among labor-affiliated investors throughout the entire 2006–14 span covered in the Proxy Monitor database. Unlike the New York State fund, the City’s funds are not solely entrusted to the fiduciary authority of the elected comptroller—currently Stringer—but allocated to boards of trustees, typically political officials or union delegates, that vary for each of the five funds managing assets for city employees.[14] The New York City funds’ shareholder activism dipped in 2013, a trend that has continued this year under Stringer (Figure 6).

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

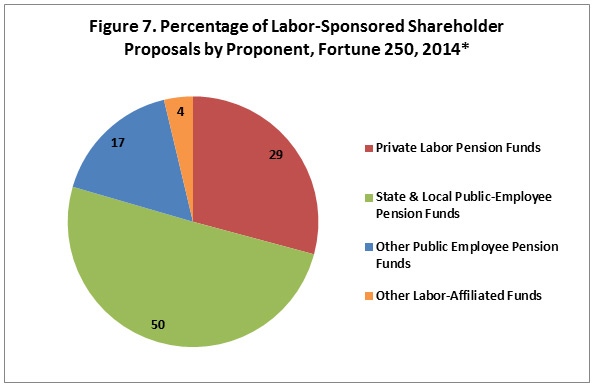

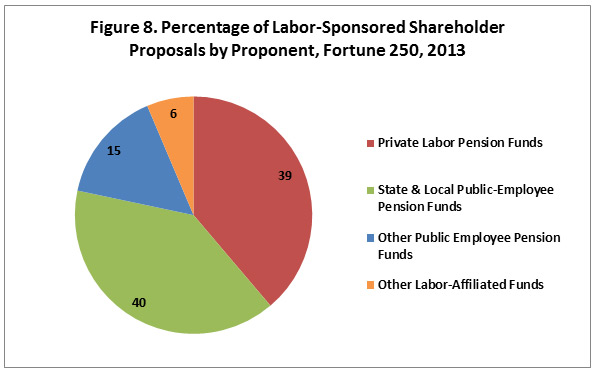

Spurred by the large role played by the New York City and State pension funds, fully 50 percent of all shareholder proposals introduced at Fortune 250 companies in 2014 by labor-affiliated investors have been sponsored by state- and municipal-employee funds, up from 40 percent in 2013 (Figures 7 and 8). In contrast, the percentage of labor-sponsored shareholder proposals backed by pension funds affiliated with private labor unions has dropped from 39 percent to 29 percent, with significant drop-offs from historically active multiemployer plans—such as the AFL-CIO, International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, United Brotherhood of Carpenters, and International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

II. Types of Labor-Backed Shareholder Proposals

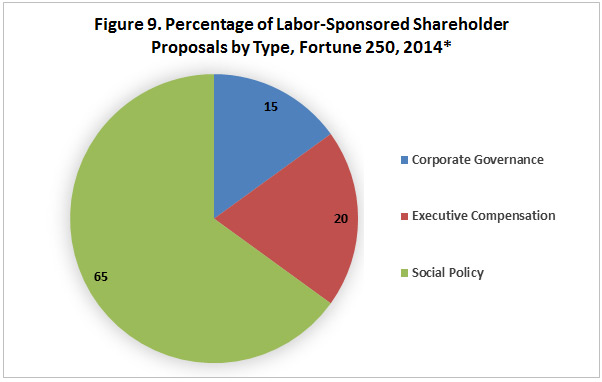

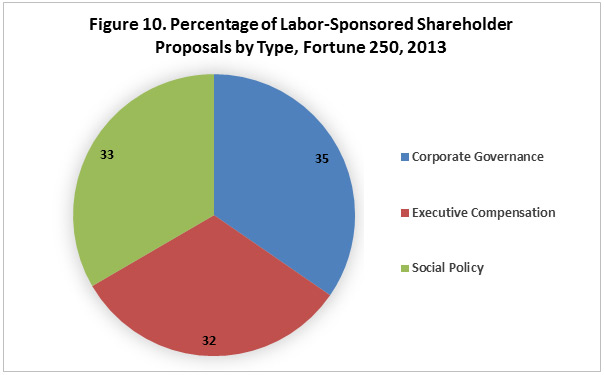

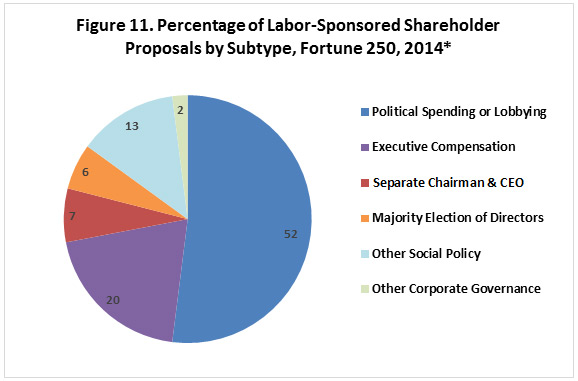

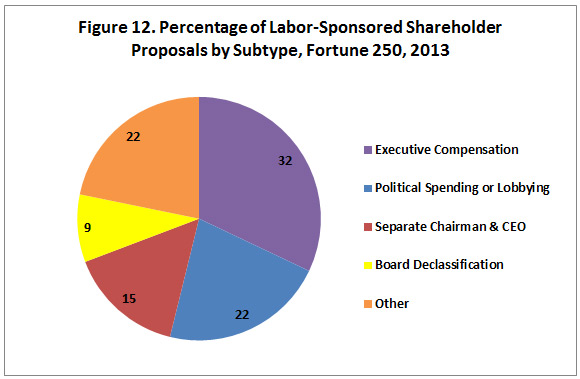

With the increased role in labor-affiliated shareholder activism being played by state and municipal funds in 2014, led by the New York State and City funds, it is perhaps unsurprising that labor-sponsored shareholder proposals this year have been more oriented toward social, policy, and political concerns than has historically been the case. Some 65 percent of all labor-affiliated shareholder proposals introduced at Fortune 250 companies in 2014 have involved social or policy concerns, as opposed to just 33 percent in all of 2013 (Figures 9 and 10). Only 15 percent of 2014 labor-backed shareholder proposals have involved traditional corporate governance issues, down from 35 percent in 2013; and just 20 percent have involved executive compensation, down from 32 percent last year.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

Whereas shareholder proposals involving corporate political spending or lobbying constituted just 22 percent of all labor-sponsored proposals in 2013, 52 percent of all 2014 proposals have involved these topics (Figures 11 and 12)—including 14 of the 19 proposals sponsored by the New York State Common Retirement Fund and all seven of the proposals sponsored by AFSCME. In contrast, only two of the seven shareholder proposals sponsored by the New York City pension funds involved political spending or lobbying; just one of the seven proposals sponsored by the AFL-CIO involved such spending/lobbying; and no proposals by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters involved such spending/lobbying.

The percentage of labor-sponsored shareholder proposals seeking to separate the chairman and CEO positions dropped from 15 percent in 2013 to 7 percent in 2014 (Figures 11 and 12). As noted by David Whissel, a research analyst with boutique proxy advisory firm Proxy Mosaic, this decline could be attributable to “the fact that labor groups, having grown frustrated by the low levels of support that these proposals generally receive, decided to abandon them, leaving the cause to be taken up by individual activists and corporate gadflies instead.”[15] Notably, individual investors have been introducing chairman-CEO proposals in greater numbers even as labor-affiliated pension funds have scaled back their efforts in this area.

Whereas 9 percent of all labor-sponsored shareholder proposals in 2013 called for declassifying the board of directors—electing each director annually, which is thought to facilitate potential takeover bids[16]—none has been introduced at any Fortune 250 company to date in 2014 (Figures 11 and 12). To some extent, this may be attributable to companies potentially facing such proposals agreeing to such a change as “a generally accepted principle of good corporate governance,” in light of past broad—and growing—support for such proposals.[17] In addition, the universe of large, publicly traded companies with staggered boards has been shrinking: as noted in the midterm report, two-thirds of the S&P 500 companies that had classified boards as of 2012 have since changed their practice.[18]

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

III. Political Spending or Lobbying Proposals

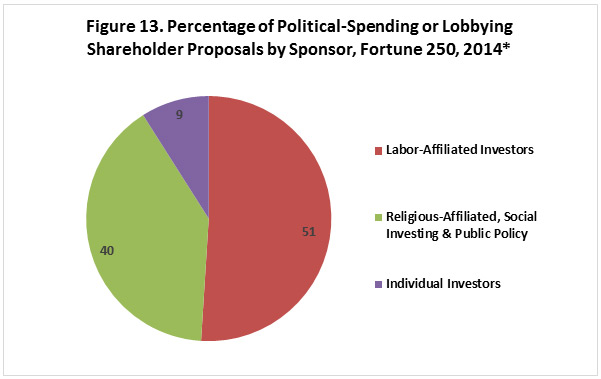

As noted, 52 percent of all labor-sponsored shareholder proposals in 2014 have related to corporate political spending or lobbying. In addition, labor-affiliated investors have sponsored 51 percent of all such proposals introduced at Fortune 250 companies this year (Figure 13).

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

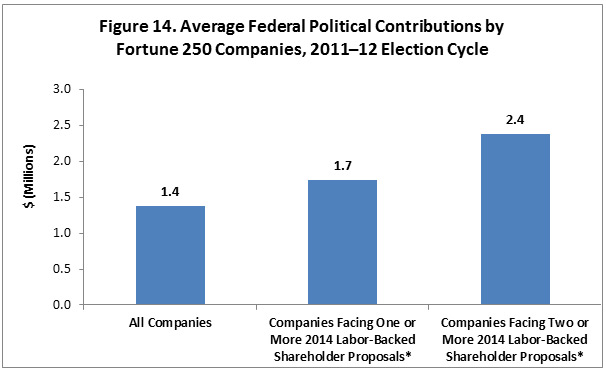

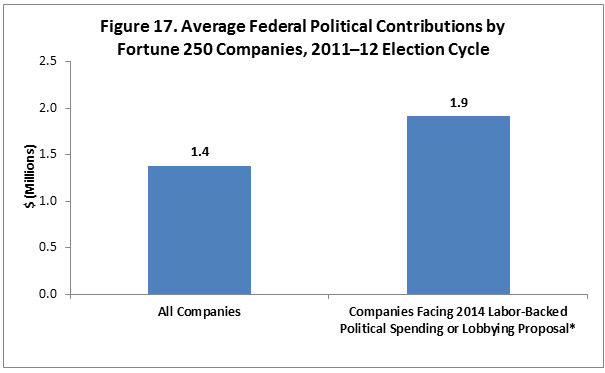

In our 2013 Proxy Monitor Fall Report, we showed that “the focus of labor-affiliated pension funds’ shareholder-proposal activism ... broadly supports the hypothesis that at least some of these funds’ efforts in this area may have a political purpose.”[19] In 2013, labor-affiliated funds were generally more likely to introduce shareholder proposals at companies that had contributed more funds to the political process in the preceding general election (through political action committees or others). Although this trend might be at least partly explained by large-company bias, we also showed that “corporations that gave at least half of their donations to support Republicans were more than twice as likely to be targeted by shareholder proposals sponsored by labor-affiliated funds as those companies that gave a majority of their politics-related contributions on behalf of Democrats.”[20]

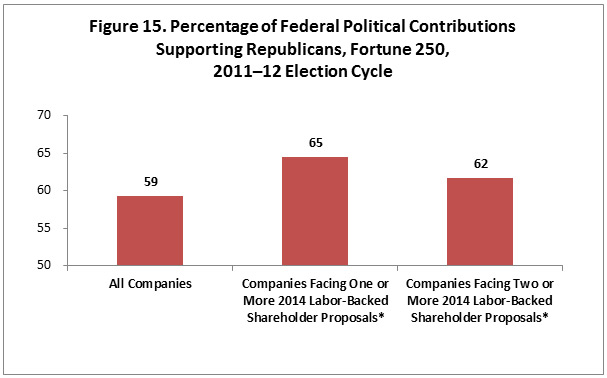

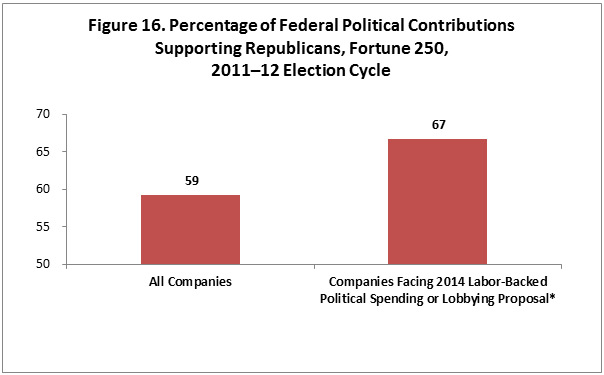

These observations also hold true in 2014. Among the 43 Fortune 250 companies facing shareholder proposals sponsored by labor-affiliated investors in 2014, only five contributed more money to Democrats than to Republicans in the previous political cycle: just under 12 percent, as opposed to almost 25 percent of all companies in the Fortune 250. Moreover, only one of these five companies faced a labor-sponsored shareholder proposal related to political spending or lobbying (Newmont Mining Corporation, which faced a political-spending-disclosure shareholder proposal introduced by the New York State Common Retirement Fund, and which gave 65 percent of its political contributions to support Democrats).[21] Overall, companies facing shareholder proposals introduced by labor-affiliated investors gave 65 percent of their 2012 election-cycle dollars to support Republicans, versus only 59 percent of all Fortune 250 companies (Figure 15).[22] The political spending of companies receiving at least one labor-affiliated shareholder proposal related to political spending or lobbying was even more skewed toward Republicans in 2012, with 67 percent of all dollars going to support the GOP (Figure 16).

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

In total, among the 26 Fortune 250 companies facing at least one labor-sponsored shareholder proposal related to political spending or lobbying in 2014, 25 gave more money to support Republicans in 2012. As noted above, two labor-affiliated pension funds, in particular, concentrated their shareholder activism in this area: the New York State Common Retirement Fund and AFSCME.

Source: ProxyMonitor.org

*219 of 250 companies reporting

Conclusion

The decline in shareholder-proposal activism by multiemployer pension plans is one of the more significant stories of the 2014 proxy season. In part, this drop is attributable to shifts in corporate practice consistent with such plans’ goals: for instance, the broader adoption of majority-voting standards for director elections at large, publicly traded companies has significantly obviated the need for such proposals, which were previously sought in greater numbers by the United Brotherhood of Carpenters pension fund. In addition, some multiemployer pension plans may have reevaluated how their shareholder-proposal activism fit into their investment strategy— whether motivated by ERISA duties or the funding concerns raised by the PBGC.

More than in any recent year, labor-affiliated shareholder activism in 2014 has been centered in the public-employee pension funds for New York City and State and the AFSCME pension fund, representing a broad swath of public employees. The New York State fund and the AFSCME fund have been almost single-mindedly focusing their 2014 shareholder-proposal activism on corporations’ political spending, principally targeting Republican-favoring companies. It may not be surprising that a state-employee fund whose sole fiduciary power is vested in a single elected Democratic official and a multiemployer fund representing employees who work for state and local governments would target (and perhaps seek to intimidate) certain companies—those firms engaged in the political process in a manner perceived as both adverse to the interests of the Democratic Party and to the cause of greater spending on public-employee wages and benefits.[23] Whether such efforts constitute good stewardship of retirees’ pension resources is another matter.

ENDNOTES

- Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376, §951 (2010) [hereinafter Dodd-Frank Act].

- Proxy Monitor, Reports and Findings, http://proxymonitor.org/Forms/reports_findings.aspx (last visited July 15, 2014).

- Twelve companies, whose annual meeting results appear in the Proxy Monitor database, were not in the Fortune 250 list for 2013 and therefore are excluded from this analysis: Aon, Ashland, Coca-Cola Enterprises, Devon Energy, Eaton, ITT, KBR, Motorola, Oshkosh, Public Service Enterprise Group, Sempra Energy, and the Williams Companies.

- For purposes of this analysis, we categorize state and municipal employee plans as “labor-affiliated.” These plans, even though they provide payouts for public-employment retirees, are not directly under the control of public-employee labor unions themselves—though, in many cases, the plans vest fiduciary duties with boards peopled in part by union delegates. For instance, the nation’s largest pension fund, that for the California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS), has six union delegates on its board in addition to seven officials appointed by elected officials or serving in an ex officio capacity; see CalPERS, Board of Administration, http://www.calpers.ca.gov/index.jsp?bc=/about/board/home.xml (last visited June 15, 2014).

- See AFL-CIO, “Pensions,” http://www.aflcio.org/Issues/Retirement-Security/Pensions (last visited July 15, 2014); and AFSCME, “Pension Security,” http://www.afscme.org/issues/pension-security (last visited July 15, 2014).

- See, e.g., Business Roundtable & Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. SEC, 647 F.3d 1144, 1152 (D.C. Cir. 2011), http://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/89BE4D084BA5EBDA852578D5004FBBBE/$file/10-1305-1320103.pdf (citing proposition that “investors with a special interest, such as unions and state and local governments whose interests in jobs may well be greater than their interest in share value, can be expected to pursue self-interested objectives rather than the goal of maximizing shareholder value”); see also OIG Department of Labor, “Proxy-Voting May Not Be Solely for the Economic Benefit of Retirement Plans,” report 09-11-001-12-121, introduction (March 31, 2011), http://www.oig.dol.gov/public/reports/oa/2011/09-11-001-12-121.pdf (questioning whether labor pension funds are using “plan assets to support or pursue proxy proposals for personal, social, legislative, regulatory, or public policy agendas”).

- Pub. L. No. 93-406, § 514, 88 Stat. 829, 897 (1974), codified at 29 U.S.C. §§ 1001-1461 (2006). Under ERISA, fiduciary duties governing employee benefit plan investment portfolios require that “in voting proxies ... the responsible fiduciary shall consider only those factors that relate to the economic value of the plan’s investment and shall not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income to unrelated objectives,” 29 C.F.R. § 2509.08-2(1) (2008).

- See 29 U.S.C. § 1003(b).

- Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, Fiscal Year 2013 Projections Report, http://www.pbgc.gov/documents/Projections-report-2013.pdf (last visited July 15, 2014).

- The NYSLRS includes the Police and Fire Retirement System (PFRS) and the Employees’ Retirement System (ERS); teacher pensions are separately managed by the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System (NYSTRS).

- Office of the State Comptroller, “Fiduciary Responsibilities of the Comptroller,” http://www.osc.state.ny.us/pension/fiduciary.htm (last visited July 15, 2014).

- Danny Hakim, “Thomas P. DiNapoli, a Nice Guy Who Wound Up Finishing First,” New York Times (Feb. 8, 2007), http://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/08/nyregion/08man.html?_r=1&; and Michael Cooper, “Hevesi Resigns, Pleading Guilty to Fraud Count,” New York Times (Dec. 22, 2006), http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/22/nyregion/22cnd-hevesi.html?_r=0.

- Aaron Elstein, “Liu Cuts to the Chase,” Crain’s (Apr. 14, 2013), http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20130414/POLITICS/304149974.

- E.g., the board of the $46 billion Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) includes the comptroller, two mayoral delegates, a delegate from the education chancellor, and three teacher delegates; see TRSNYC, “Our Retirement Board,” https://www.trsnyc.org/trsweb/aboutUs/ourRetirementBoard.html (last visited July 15, 2014). The board of the $43 billion New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) includes the comptroller, the public advocate, a mayoral representative, each of the five New York City borough presidents, and three union delegates; see NYCERS, Board of Trustees, http://www.nycers.org/(S(azvv04mpy1qd2j5515dyny55))/about/Board.aspx (last visited July 15, 2014).

- David Whissel, “Proxy Mosaic: 2014 Proxy Season Review,” http://www.proxymosaic.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2014-Proxy-Season-Review-White-Paper.pdf, 7.

- Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Charles C. Y. Wang, “Staggered Boards and the Wealth of Shareholders: Evidence from Two Natural Experiments,” NBER Working Paper 17127 (June 2011), http://www.nber.org/papers/w17127.

- Whissel, “Proxy Mosaic,” 8.

- Harvard Law School Shareholder Rights Project, “Companies Agreeing to Move Toward Annual Director Elections,” http://srp.law.harvard.edu/companies-entering-into-agreements.shtml (last visited July 15, 2014), 121.

- James R. Copland and Margaret M. O’Keefe, “Proxy Monitor 2013: A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism” (Manhattan Institute, Fall 2013), http://www.proxymonitor.org/pdf/pmr_06.pdf, 8.

- Ibid.

- The other four companies that gave more money to Democrats and were targeted by labor-affiliated pension funds seem to have been selected for other reasons. The labor-affiliated Amalgamated Bank, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and the AFL-CIO, respectively, introduced proposals at Avon, Comcast, and DuPont, addressing the accelerated vesting of change-in-control equity awards for management—commonly called “golden parachutes” by critics. DuPont also faced a proposal by its company-affiliated pension plan seeking a report on plant closures. Finally, the Massachusetts Laborers’ Pension Fund and the Firefighters’ Pension of Kansas City, Mo., each introduced proposals at Google, respectively, seeking to separate the company’s chairman and CEO positions and to require directors to win majority shareholder support for election.

- Dollar figures contributed per company as well as the percentage of funds going to Republicans vary somewhat from the data shown in the 2013 Fall Report because of changes in the composition of the Fortune 250 and changes in reporting by the Center for Responsive Politics, whose data serve to undergird this analysis. Overall dollars contributed are skewed upward by the extraordinary amount spent by billionaire Sheldon Adelson, chairman and CEO of Las Vegas Sands, in the 2012 election cycle; excluding Las Vegas Sands would significantly lower the average number of dollars per Fortune 250 company associated with the 2012 election but would not otherwise affect this analysis.

- I should note that I am not accusing the AFSCME pension fund of failing to comply with its fiduciary obligation, under ERISA, to manage its affairs to maximize share value. AFSCME’s shareholder proposal, ostensibly about corporate lobbying, is designed to ferret out corporate contributions to 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations (such as Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS or Organizing for Action, a Democrat-supporting organization affiliated with Obama campaign operatives); to 501(c)(6) trade associations (such as the Business Roundtable and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce); and to 501(c)(3) organizations that introduce model legislation (chiefly the free-market-oriented American Legislative Exchange Council, which proposes model bills for potential adaption and adoption by state legislatures). In recent weeks, outside the pension-fund context, AFSCME has flexed its muscles in a political context by cutting ties with the United Negro College Fund after the organization accepted funding from the Charles Koch Foundation, affiliated with billionaire Charles Koch (chairman and CEO of Koch Industries and historically a strong backer of libertarian causes); see Fredreka Schouten, “AFSCME Union Cuts Ties with United Negro College Fund Because It Accepted Koch Donation,” Fox News (July 11, 2014), http://nation.foxnews.com/2014/07/11/afscme-union-cuts-ties-united-negro-college-fund-because-it-accepted-koch-donation.